The recent crackdown on China’s Big Tech has attracted significant international attention. In November 2020, Jack Ma, the founder of China’s prominent Alibaba Group, including its subsidiary the financial technology giant Ant Group, sharply criticized China’s banking regulation at a conference in Shanghai before Ant’s IPO. In his words, the “pawnshop mentality” of Chinese banking regulators rendered them incapable of delivering the freedom necessary for financial innovation. The conference was attended by high-level officials who oversaw banking and security sectors, and their silent rage would be felt almost immediately. President Xi Jinping reportedly ordered the suspension of Ant’s IPO, which would have been the largest in financial history. Alibaba was subsequently fined 2.8 billion USD for its monopolistic practices and has been flooded with negative media coverage, including recent accusations of rampant internal sexism. Alibaba’s stock price and market capitalization have plummeted roughly 50% year-to-date with no rebound in sight.

The Chinese government is determined to make an example out of Alibaba while examining similarly problematic behaviors on the part of Alibaba’s rivals. Tencent, the internet conglomerate behind China’s omnipresent online communication app WeChat, has also suffered from Beijing’s intense scrutiny of its gaming empire. Millions of minors in China are now banned from playing video games during weekdays, and Tencent is expected to comply strictly by widely deploying facial recognition to restrict minors’ access to its games.

WeChat Pay and Alipay, mobile payment platforms that are the crowning jewels of Tencent and Alibaba respectively, have transformed China into a near-cashless society in less than a decade. Their products penetrated every aspect of Chinese life, their market dominance intractable. However, time has changed. No companies are too big to fall even if they are the leviathans of Chinese technological prowess. Although several other minor players in China’s tech industry have been spared from similar penance, the volatility of their stock prices has demonstrated a similar cost of uncertainty.

Mainstream media in the West has largely characterized China’s crackdown as a concerted effort by the Chinese Communist Party to rein in Big Tech, but commentators and analysts have not agreed on the root causes or purposes of the crackdown. Based on analyses of Chinese popular online press, some have argued that growing economic inequality in China has made regulation over the “haves” a popular move among the “have-nots.”

China’s decision to reform its economic system in the late 1970s has been rewarded by extraordinary progress in the last four decades. Hundreds of millions of urban and rural residents have been lifted out of poverty, but the rural-urban divide is more troubling than ever, and the younger generations often lament the lack of opportunities that were only available to the generation of Jack Ma. Social mobility in China is perceived to be increasingly stagnant. The socioeconomic significance of “connections” (knowing the right person) has not diminished. The middle class is investing heavily in their children’s education, hoping that their children will be able to continue to climb upward. The burden of living in major cities has not been meaningfully alleviated despite continuous reforms. Similar to the San Francisco Bay Area, the wealth generated by the tech boom has not been equally distributed in Beijing or Shenzhen.

In this sense, the crackdown on tech is embodied in an overdue systematic realignment of domestic interests and correlates with intense regulatory pressures that are being simultaneously applied to other sectors including real estate, education, and cryptocurrency. Tapering off growth in high-risk sectors that exacerbates income inequality and fuels systemic risks is already a regular political theme in China, and Ant’s allegedly irresponsible lending practices fall neatly under that category. Others suspected that the crackdown was a signal of more incoming changes in China’s economic policy, such as the role of the state being underscored more heavily. This would represent a divergence from China’s previous attempts to promote the natural functioning of the market through moves such as as relaxing currency exchange controls.

The timing of the crackdown is also unusually significant and the stakes are higher than ever. The sixth plenum of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in November 2021 has been deemed to be a crucial juncture of President Xi’s tenure. The 20th Party Congress of the CCP will be held next year, and a major reshuffle of the top leadership is expected.

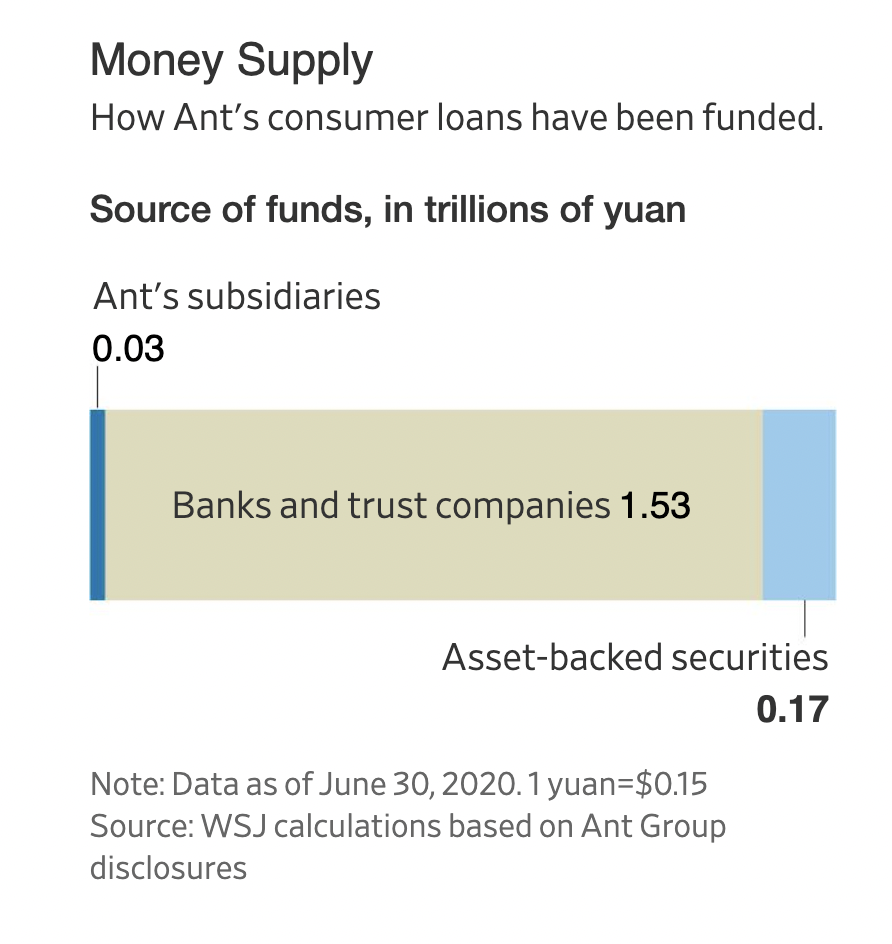

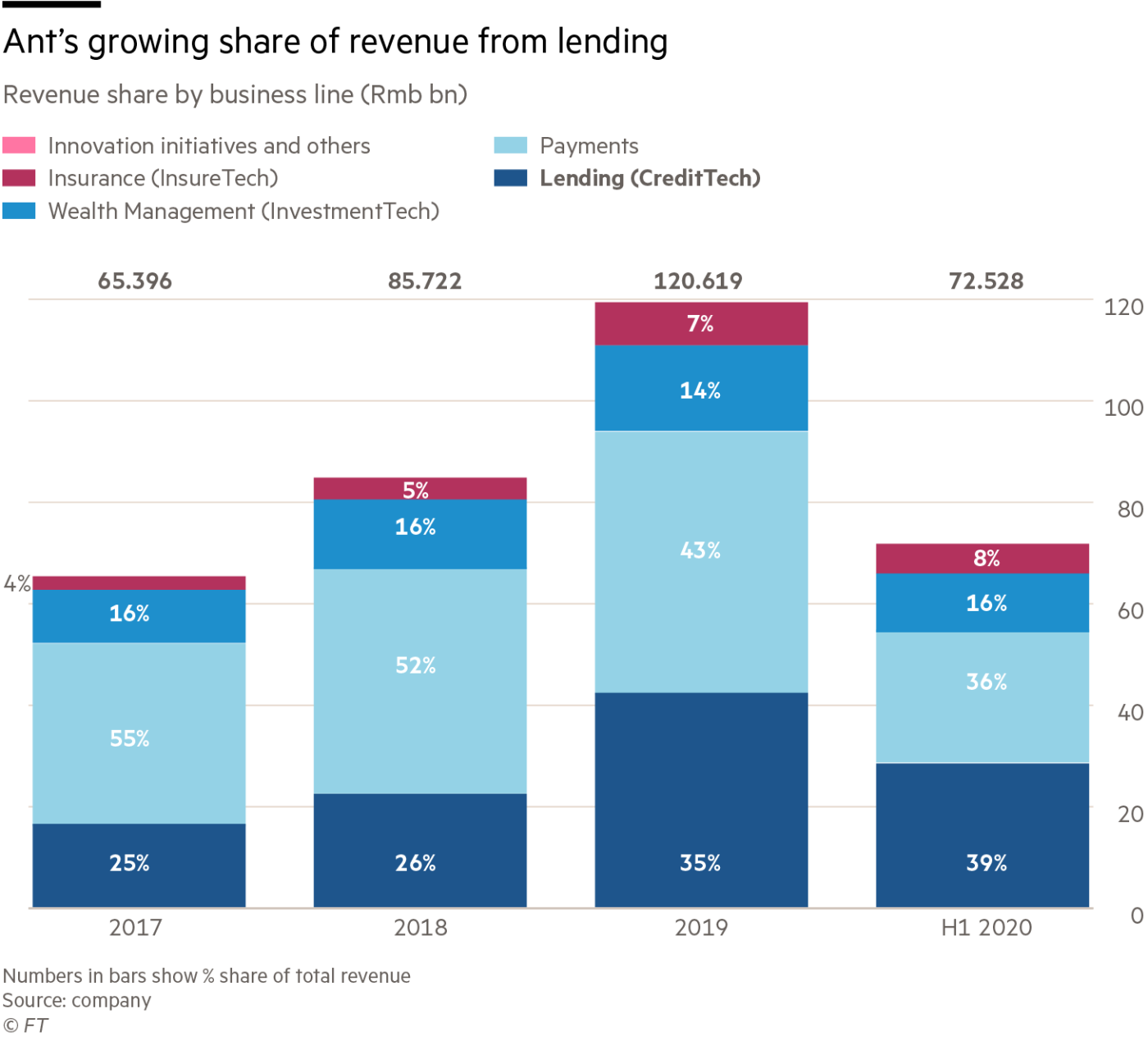

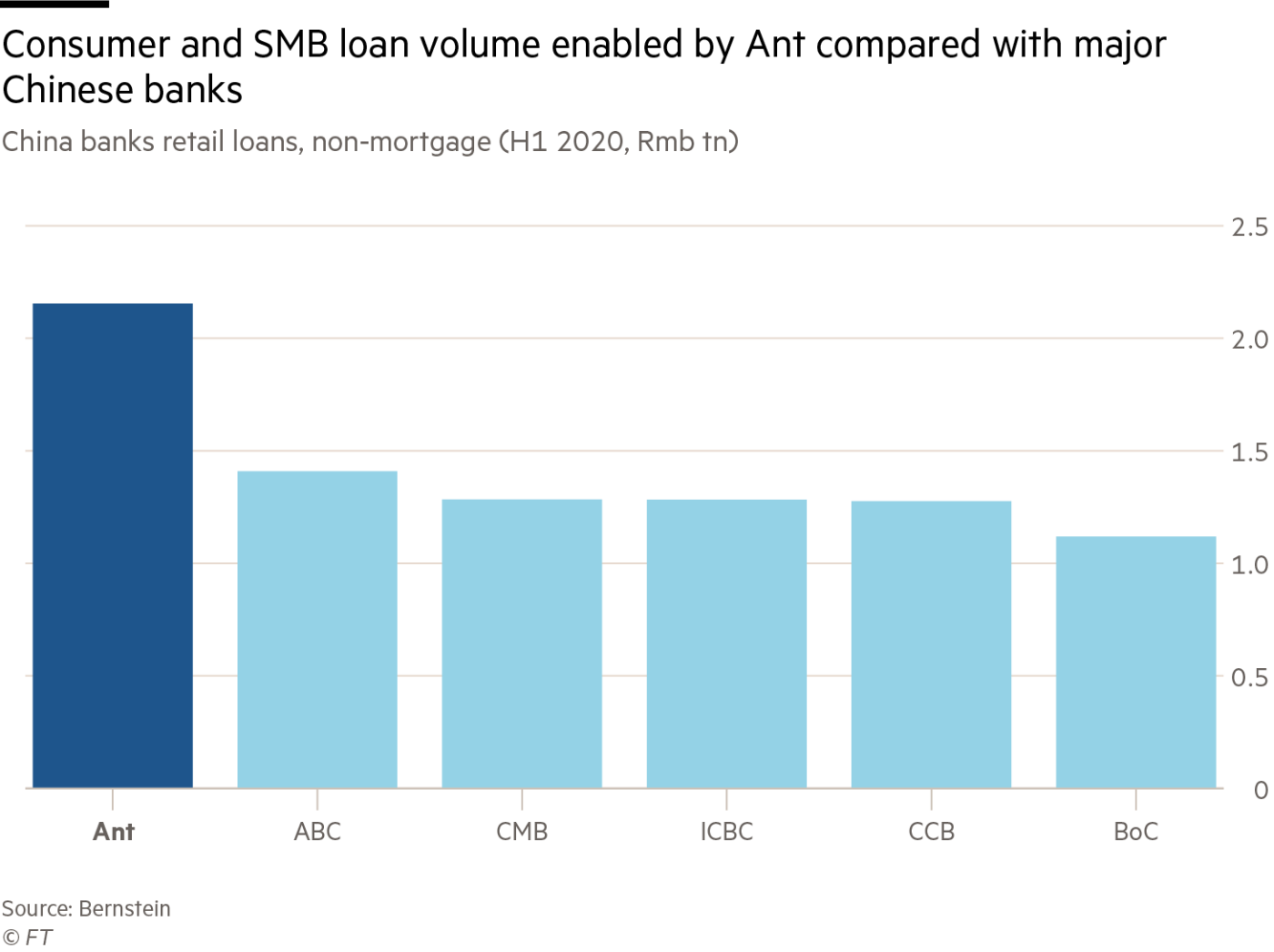

A few experienced China watchers, including prominent economist and journalist David Goldman, who hailed the recent moves as “[an] attempt to avoid the American tech monopoly trap.” Goldman rejected the notion of crackdown and called it misleading, while acknowledging politics were always involved. He juxtaposed China’s heavy-handed approach to cap Ant’s excessive leveraging with the failure of American regulators to prevent the 2008 subprime mortgage crisis. For instance, by end of June 2020, Chinese consumers had borrowed at least $230 billion via Alipay, and as an intermediary between banks and consumers, Ant is not subject to China’s banking regulation. Thus, it has profited billions of dollars from facilitating lending while having virtually no responsibility for the loans that it originated. In other words, Ant’s practice is the very definition of moral hazard.

In Goldman’s view, the Chinese leadership is keenly aware of the dangers induced by an under-regulated financial industry and has the political determination to curb excessive risk. Beijing is forcing Ant to transform itself into a financial holding company, which will require Ant to comply with all banking laws and be responsible for risks that it generates. However, dealing with a fintech giant like Ant is inherently and unprecedentedly complex, and Chinese banking regulation agencies might face a steep learning curve.

The U.S. encountered monopolies back in the days of Standard Oil and U.S. Steel, while China was not able to produce corporations of similar sizes until decades after Deng’s economic reform in 1978. Therefore, it is not surprising that China saw no need for antitrust law until 2007. From this perspective, China lacks experience in antitrust regulation (both in legislation and enforcement) relative to the U.S. However, one thing that China never lacks is political determination. The swiftness and the scale of anti-monopoly enforcement demonstrated by the Chinese regulators likely have impressed their American counterparts.

New York Magazine writer Eric Levitz juxtaposed the Chinese outcome-oriented approach with the interplay of money and politics in America in his recent article, lamenting that Uncle Sam is essentially powerless now when American superstar firms challenge their government’s regulatory sovereignty. “If Washington is in a populist mood,” Levitz quipped, “adversarial entrepreneurs can expect a tongue-lashing on C-SPAN and a years-long investigation that might yield a fine of negligible size.” The implications of weakened American antitrust regulation are twofold. Domestically, there are calls to regulate American Big Tech as the new utilities in the modern age since they have not been held accountable for a myriad of damages inflicted on American society by their thorny algorithmic infrastructure. In his address to Congress in 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt warned: “The first truth is that the liberty of a democracy is not safe if the people tolerate the growth of private power to a point where it becomes stronger than their democratic state itself.”

Although the political systems of the two countries in question are antithetical, the scales of the potential threats to their systems are of the same magnitude. Levitz characterized China’s approach to Big Tech as “progressive authoritarianism” that symbolized China’s firm intention to address systematic economic issues, while the response of the West to similar challenges was far from adequate. The fear of long-term global divergence in the field of antitrust is tangible.

Ray Dalio, the founder of the international investment firm Blackstone, also offered his insight. He has reportedly cultivated close relationships with the Chinese leadership, and his subtle understanding of China reflects his first-hand experience. Blackstone has benefited from China’s economic rise by establishing a major presence in the Chinese financial landscape and receiving investments from the Chinese government. Given his background, he did not hesitate to debunk the recent doomsaying. “For example,” Dalio said, “[firms] need to not mistake their having riches for having power for determining how things will go.” He believes that those in the capital markets must recognize their subordinate status in the system, or they will suffer the consequences for crossing the unspoken line.

Indeed, “not mistake their having riches for having power” encapsulates the complex relationship between the government and big business in China that can be traced back centuries. Western journalists have frequently been perplexed by the existence of unwritten rules that govern relationships between government and business, large and small. Their unfamiliarity with the Chinese reality often results in simplistic analyses that perpetuate unnuanced narratives. If the government-business relationship in China is examined in a broader historical context, its complexity should come as no surprise. The attitude of the Chinese Communist Party toward major private enterprises since 1978 has been nonuniform and occasionally ambivalent, which mirrors the mentality of various rulers of Imperial China toward big businesses and their owners. In Book of Documents, a classic by Confucius, Chinese society was divided into four categories, or “four occupations”: scholars, peasants, craftsmen and merchants. Scholars enjoyed the highest social status while merchants were dismissed as the lowest class. The different valuations of occupations within this social hierarchy stemmed from the agrarian nature of Chinese society, since the proposed social hierarchy was not based on perceived virtue but on economic priorities as Philip Kuhn asserted. In imperial China, agriculture was considered the “root” occupation since the agricultural tax was the primary source of the state’s fiscal income. Businesses were considered indispensable for the smooth exchanges of goods but always politically secondary. Mercantile barons had to submit to the political elite and refrain from interfering with politics, despite the fact that the relations between the merchants and the politically powerful were consistently corrupt.

The Confucian value system, as a product of a historical trajectory that is vastly different from its Western equivalents, is deeply ingrained in the Chinese way of governance. Since the time of Confucius, attitudes toward merchants have evolved but have not deviated far from tradition. The need to influence private enterprises when necessary is not just a natural requirement stemming from Communist ideology, but a manifestation of the desire to maintain a harmonious Confucian society that is free from undue interference. Today, the economic freedom of Chinese residents and companies is granted by the Chinese Communist Party. Similar to its dynastic predecessors, the Party will never allow internet giants or any other entities to go unpunished after publicly humiliating the government. Or the neo-Confucian ideal of “harmonious society”, put forward by President Xi’s predecessor to maintain stability in the Chinese gilded age, would be in jeopardy.

In the long run though, the concerns of stifling innovation raised by Jack Ma are valid. The founding of Alipay was a challenge to the walled-off banking world controlled by state-owned banks of tremendous sizes. Alipay’s technological capability has created considerable financial instability, but it has also democratized finance for a massive rural Chinese population, whose access to banking is otherwise limited. It has alleviated the financial-digital divide between urban and rural China and improved banking experience. In addition, this digital payment revolution ignited by Alibaba and Tencent has profoundly transformed China’s financial landscape as shown by the omnipresence of banking QR codes in China.

According to the People’s Bank of China (PBOC), the volume of digital payments hit 41.51 trillion U.S. dollars in 2018. China is one of the most cashless societies in the world, which is indeed stunning given its geographical scale, the size of its population, and a GDP per capita one-sixth of that of the U.S. The ubiquity of mobile phones is a prerequisite of the ongoing digital payment revolution, and the role of the two Internet giants is quintessential. China is currently developing and piloting its digital currency in the hope of bypassing private enterprises and gaining control over the spending data of its citizens. A war on tech will certainly be factored into the future dynamics between private payment services and the central bank when digital currency officially circulates.

Dr. Angela Zhang, an assistant professor at the University of Hong Kong, proposes that the People’s Bank of China has functioned as a sector regulator and leveraged antitrust law to reassert its authority over the financial industry. In her new book Chinese Antitrust Exceptionalism: How The Rise of China Challenges Global Regulation, she reveals the “behind-the-scenes” of Chinese antitrust actions by situating them into the vast bureaucratic apparatus. Unlike the heated exchanges in the Senate’s hearings, China’s antitrust actions are products of the turf wars between different yet similarly powerful regulators and the tug-of-war between regulators and conglomerates.

For Alipay-level innovation to blossom, China still needs Deng Xiaoping’s courage to welcome challenges posed by technology as well as the wisdom to continue to unleash its economic potential. The existence of Big Tech is a hallmark of a strong modernized state and an indicator of a technology-fueled future, but China will need to understand how to translate technology into higher productivity across the board, as well as formulating localized responses to the negative societal effects of Big Tech that are far more visibly stinging than the invisible financial risks.

Antitrust and anti-monopoly policies are instrumental in China’s crackdown on Big Tech. If China wants to go down the path of antitrust to thoroughly regulate the tech industry and broadly restructure its market economy, it must also reckon with the monopoly of its state-owned enterprises (SOEs). President Xi has re-emphasized the role of SOEs in his vision for a stronger, more self-reliant socialist economy and “common prosperity.” SOEs have long been deemed as the safeguard of the socialist nature of the state and the primary instruments of state capitalism. In the post-Mao period, major reforms of SOE in the 1990s were painful, and the current minor restructurings are often ineffective. Today, all major players in key industries, such as oil, electricity and telecommunication are state-owned enterprises. If the long-existing monopoly of SOEs is not addressed for ideological reasons, further economic reforms will be thwarted and the issue of selective application of antitrust law will continue to be raised.

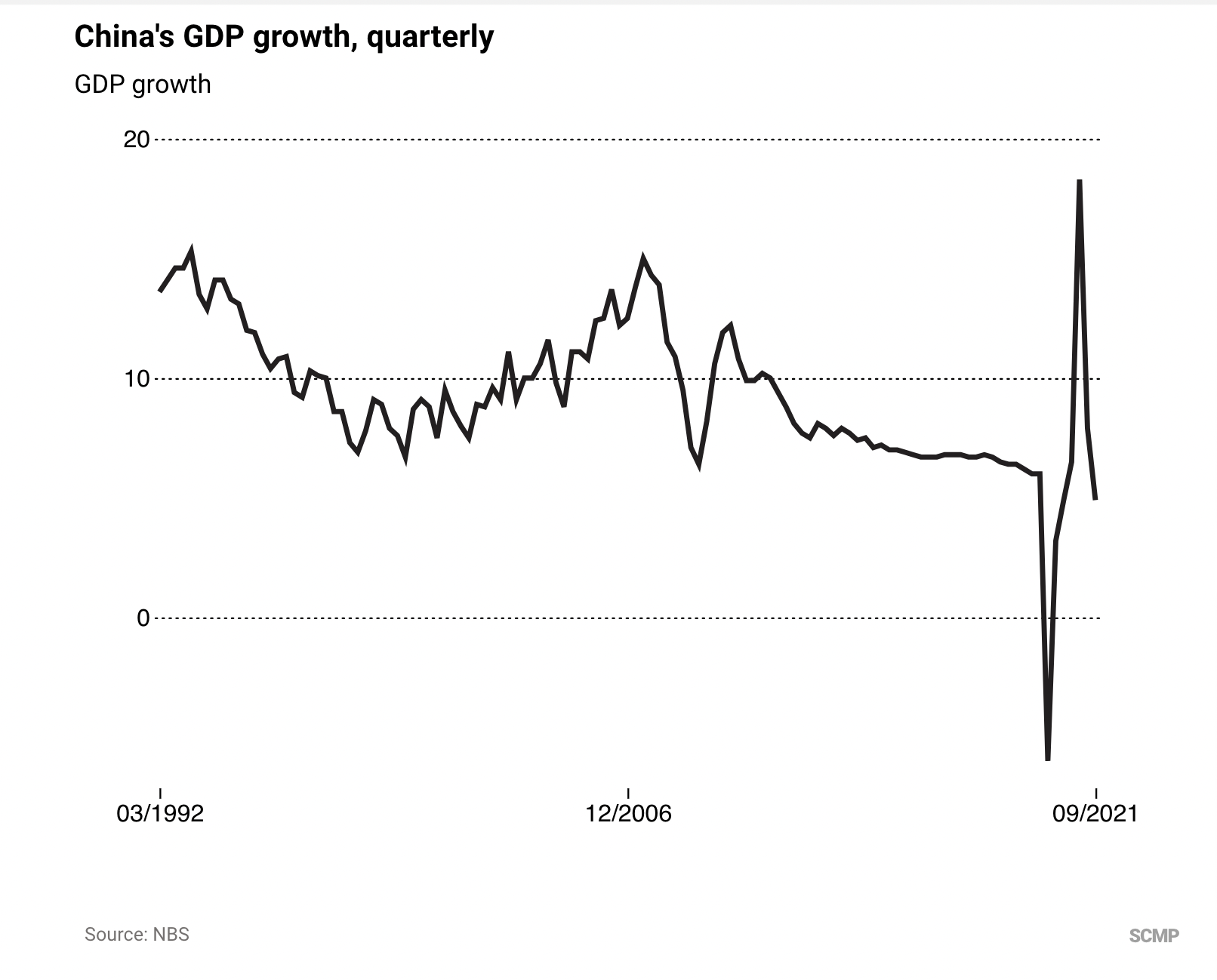

Today’s heavy-handed approach delivers immediate results and corrections in courses, but it has inevitably attached chilling messages. Striking a balance between adequate regulation and sufficient space for progress is always a delicate act. Without a relatively free, pro-business atmosphere, China will fail to continue to capitalize on the innovations of its army of private enterprises and their competent engineers. The Chinese economy grew only 4.9% in the third quarter, in stark contrast to the 7.9% growth in the previous quarter. The slowdown has been attributed to widespread power shortage, real estate plight and the tech crackdown. Despite the warning sign, the possibility of a continuing systemic slowdown remains low. The Chinese economy is expected to pick up its previous speed as soon as the government reverses course or the targeted structural economic issues are successfully overhauled. However, the latter is possible only if the government is willing to tolerate a low growth rate for an extended period and deal with various discomforts, a Herculean endeavor. The outcomes of the multi-front offensive against long-existing structural challenges are far from certain, and it is premature to ascertain whether Beijing’s current bold maneuver will ultimately triumph.

China’s war on tech isn’t over. Neither is the tumultuous Chinese gilded age.

Featured Image Source: The New York Times

Comments are closed.