In the last few years, Facebook, Apple, Google, and Amazon have dominated the news, and at the same time have become increasingly involved in every aspect of our lives. Calls to break up and/or regulate these corporations have recently picked up momentum, specifically motivated by the 2020 House Judiciary Committee report concluding that “Big Tech” giants do indeed hold monopoly power over the tech industry.

As the New York Times succinctly summarized, Amazon “sets the rules for digital commerce,” Apple “favors its own apps and services on its devices,” Facebook holds “monopoly power over social networking,” and Google steals information from “third parties without permission to improve search results.” The increasing concentration of market power that these few companies have captured, and the ways in which it gives a handful of unelected individuals power over democratic processes, is being treated as a significant policy issue.

This is where antitrust steps in. Antitrust laws allow the government to take action to prevent and regulate monopoly formation and promote competition.

Over the last hundred years, the changing economic landscape has inspired new interpretations of antitrust laws that, upon developing into the dominant ideology of the time, have faced retaliation. The last century can be separated into five distinct waves that have demonstrated the tensions between each movement.

1880s-1900s: Roosevelt Assembles the Antitrust Building Blocks with the Help of John Sherman

After the Civil War, the economy was massively transformed by industrialization. This period, known as the Gilded Age, featured the concentrated growth of the oil and electricity industries and the rise of railroad conglomerates. Public discontent with this growing monopoly power led to the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887, which created the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC), an agency in charge of monitoring and regulating the transportation industry. This was the precursor to the Sherman Antitrust Act, which was passed in 1890 in response to the consolidation of large corporations such as Standard Oil Co. The act was intended to prevent the cartels, trusts, and/or monopolies from controlling certain markets as well as outlaw conspiratorial and collusive behavior that restrained trade. By 1914, under President Theodore Roosevelt, the Clayton Act was passed to specify and elaborate on the provisions in the Sherman Act. Additionally, the passing of the Federal Trade Commission Act created an agency to enforce antitrust law.

Up until Roosevelt’s administration, the Sherman Act was ambiguous and poorly enforced. For instance, in United States v. E.C Knight (1895), the Supreme Court ruled that the American Sugar Company did not have monopoly power despite controlling roughly 98% of sugar refining in the U.S. Not until cases like United States v. Addyston Pipe & Steel Co. (1898) and Northern Securities Co. v United States (1904) did Roosevelt employ the Sherman Act and break up companies based on set principles about monopoly behavior. In the infamous Standard Oil Co. v. New Jersey (1911), the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the government, breaking up Standard Oil, the largest oil refiner in the world. This case, as well as U.S. v. American Tobacco Company (1911), showcased the government’s new ability to captain antitrust laws by appropriately interfering when businesses didn’t allow for competition.

1900s-1930s: Testing out the Antitrust Infrastructure

Following the creation of the antitrust foundation, the government engaged in a trial and error period, correcting decisions in the past and defining more clearly behavior that threatened competition.

This is well-illustrated by the 1912 presidential election, a four-way race between Woodrow Wilson, William Howard Taft, Theodore Roosevelt, and Eugene Debs, each with a different vision for antitrust policy. Wilson ended up winning, but Roosevelt’s vision remained. Their conflicting views were representative of the Court’s decisions: a fight between regulating competition and regulating monopolies in how best to face anti-competitive forces.

For instance, the Court clarified its view of information sharing in Maple Flooring Mfrs. Ass’n vs. U.S. (1925), ruling that the sharing of information did not violate the constraint of trade as long as it did not entail price-fixing agreements. This decision overturned prior rulings in Eastern States Retail Lumber Dealers’ Ass’n v. United States (1914) and American Column & Lumber Co. v. United States (1921) where information sharing among competitors was viewed to be anticompetitive. Similarly, in Appalachian Coals Inc. vs. U.S. (1933), price fixing was made easier, despite the previous ruling in U.S. vs. Trenton Potteries (1927) where price fixing was ruled in violation of the Sherman Act, even when considering “reasonableness of the fixed prices.” Moreso, in U.S. vs. U.S. Steel (1920), the Supreme Court established that size alone could not sufficiently justify finding that competition was obstructed.

1930s-1950s: Franklin D. Roosevelt and The New Deal ‒ Antitrust Structure Regains Form and Integrity under Government Control

In response to the Great Depression, the federal government and states were given greater power. The New Deal removed provisions that previously designated certain actions as constraints to trade which laid the foundation for Supreme Court rulings in favor of states’ power to protect the public interest. In Nebbia vs. New York (1934), the court ruled in favor of the state for setting a minimum price for milk that Nebbia, the store owner, had violated. Similarly, in Old Dearborn Distributing Co. v. Seagram-Distillers Corp. (1936), the court ruled in favor of the state’s power to fix prices, even beyond necessity goods. Beyond expanding state regulatory powers, Wickard v. Filburn (1942) extended federal regulatory powers by expanding government reach to economic activity “indirectly related to interstate commerce.”

There was a brief disruption to the Court’s ruling in favor of government power when Thurman W. Arnold was appointed to the Antitrust Division in 1938; this was quickly curtailed by the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950 which expanded federal antitrust reach. Throughout the 1960s, unbridled government involvement continued, only to soon face sharp retaliation.

1960s-1990s: Robert Bork and the Re-Defining and Re-Building of the Antitrust Infrastructure

The Supreme Court continued to expand what was considered illegal in cases like Brownshoe Co. vs. U.S. (1962) and Utah Pie vs. Continental and Banking (1967). In U.S. vs. Von’s Grocery (1966), the Court ruled in favor of the government despite the Von’s Grocery merger being with one local grocer in LA and resulting in a cumulative 7.5% share of the local market. As Eleanor Fox, a professor at NYU School of Law describes it, the Supreme Court was “the little boy who was trying to spell banana without knowing where to stop” (with the “anana” part). This was the backdrop against which Robert Bork rose to prominence.

In arguably the most influential book on antitrust law, The Antitrust Paradox, Bork presents his readers with a paradox: antitrust laws, designed to fuel competition, were actually thwarting competition. He provided an alternative economic framework for judging competition called the consumer welfare standard. In the past, antitrust law was about how small businesses and competitors were affected by big business, but Bork instead reoriented the focus around protecting consumers. If a business in question provided better quality goods at lower prices to the consumer (which he equated to the economic efficient outcome), he deemed that the business should not be in violation of antitrust laws.

Bork’s new reasoning was applied in cases like Continental T.V., Inc. v. GTE Sylvania, Inc. (1977), which applied the consumer welfare standard and thus altered what was included as a restraint on trade. In this case, the Court ruled that price restraints within the supply chain could stimulate competition between brands to the consumers advantage. In a number of cases, like United States v. Waste Management (1984), it was ruled that easy entry into the market would prevent mergers from developing monopolies. Again, in cases like the United States v. Baker Hughes Inc. (1990), the Court communicated its newly permissive stance on mergers and acquisitions which abided by the consumer welfare standard. With more forgiving guidelines around mergers, companies could capture more market share than previously allowed (which some argue has allowed tech giants to become so massive).

Lastly, in Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd. v. Zenith Radio Corp. (1986), it was ruled that ineffective pricing schemes by Japanese manufacturer Matsushita, against American firm Zenith, invalidated any concerns with competition. The inefficiencies of price scheming, the economic effects, were more important in deciding on if an action was anti-competitive, and thus in violation of antitrust laws, than the act itself. Economic efficiency became the ultimate master, with its disciples acting in favor of consumer welfare.

This new economic jurisprudence was largely solidified in Reiter vs. Sonotone (1979) where it was stated that the Sherman Act was designed as the “consumer welfare prescription,” a year after the Antitrust Paradox was published (by 2014, “consumer welfare” had been quoted by judges 29 times).

Yet, there were exceptions to these Chicagoan rulings that set the stage for the progressive retaliation. In U.S. vs. AT&T (1982), after seven years of tug-of-war with the law, AT&T was finally broken up into seven smaller companies, one of which becoming Verizon. In U.S. vs Microsoft (1998), the Court ruled that Microsoft demonstrated monopoly-like behavior with its restrictive licensing agreements and the way it bundled competing browser web browser Netscape Navigator with it’s own Internet Explorer. This lawsuit is eerily similar to the suits filed against Google. Tech giants like Google, in the digital economy, have created an environment ripe for a new leader to challenge conventional thinking.

1990s ‒ present: Lina Khan ‒ Modernizing the Antitrust Structure

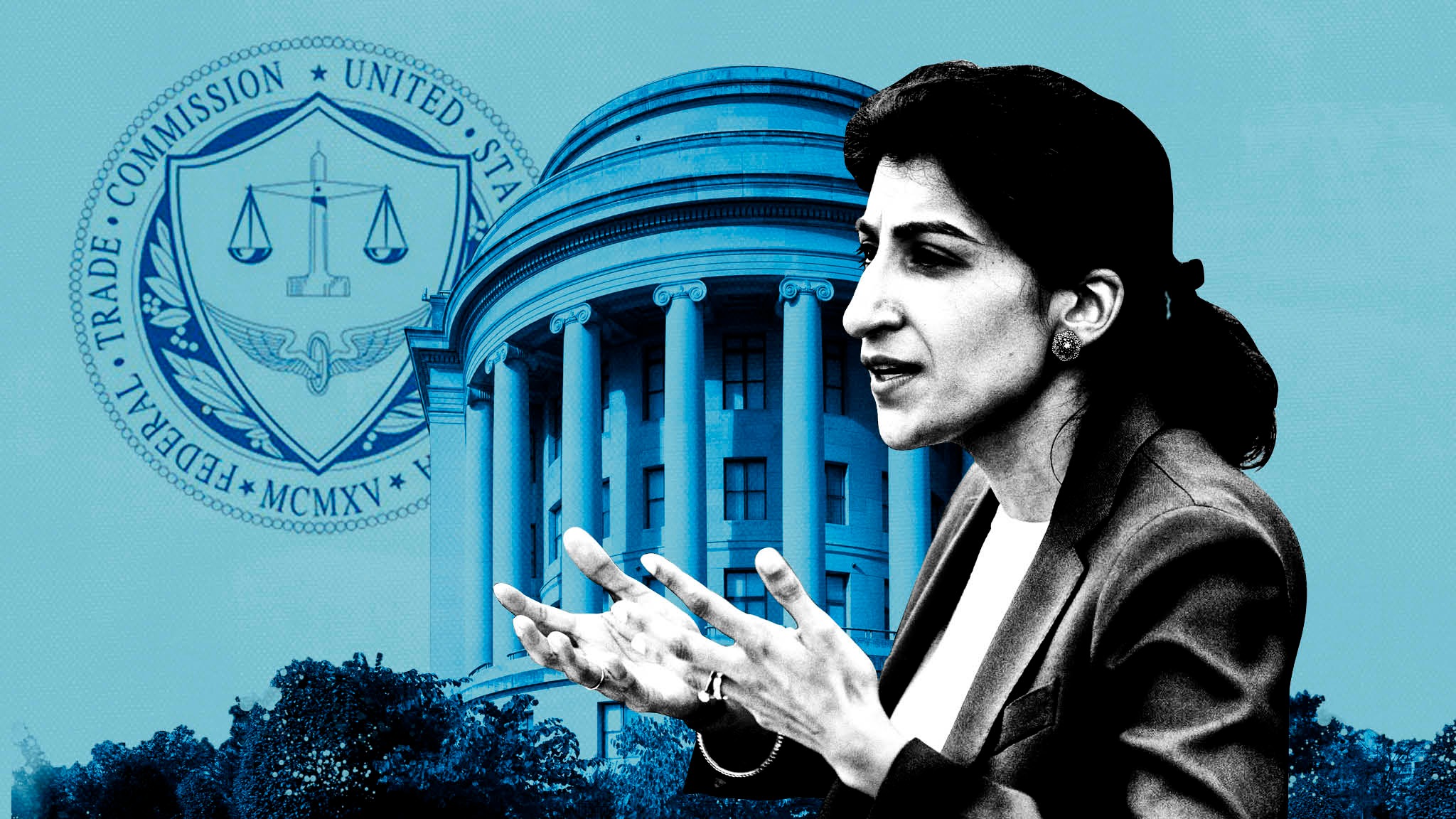

Even at the height of Robert Bork’s fame, there were those on the fringe questioning the Chicago School’s free-market conception of competition. These outsiders today are known as the “New Brandesians,” based on the old progressive “Brandeis” movement (named after Supreme Court justice Louis Brandeis). Moving from the periphery to the center, Lina Khan appears to be at the helm of the dissent against the Chicagoan creed.

Her article for the Yale Law Journal in 2016, “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” echoes the infamous title of Bork’s book that altered the future of antitrust. In direct opposition to Bork, Khan argues that the “consumer welfare standard” has led to anti-competitive behavior because it defines low prices as favorable to consumers, when, in reality, tech giants are given a “free pass” because they don’t charge anything for their products. In other words, consumers are “paying in data.” In her analysis, she discerns that Amazon can reap rewards for products it doesn’t take risks in creating and bringing to market, which disincentives start-ups from going through this process if they (rightfully) assume their value will be swallowed up by Amazon. In the long run, she believes this will lead to less competition.

To Khan, the Sherman Act, Clayton Act, and FTC act were about more than fair prices. When companies grow so big, they not only disturb competition in the market, which other players are then forced to take part in, but establish the power that can corrupt the government.

Accordingly, she wants to place greater emphasis on checking market concentration, through the lens of protecting democratic institutions. The brunt of her argument to regulate these tech giants rests on the idea that dominant digital platforms are considered public utilities, “essential faculties” in antitrust terms, and thus must be watched closely. Consumer welfare and economic efficiency analysis do not suffice; instead, “total welfare” appears to be becoming the new standard.

Lina Khan will be able to employ these Brandeisian values through her position as head of the Federal Trade Commission. Biden appointed her to spearhead the actions he plans to take, laid out in his executive order which takes a hard stance on addressing monopoly power in larger corporations, specifically big tech. Khan will be prepared to battle it out in these industries, particularly given her participation in the 2019 House Judiciary Committee’s investigation of Amazon, Apple, Facebook, and Google.

So, Lina Khan or Robert Bork? Whose Antitrust Building is Better?

In the same way Bork rose to prominence after his book’s publication and was nominated for a position by Reagan and served under Nixon, Khan has become more publicly recognized and politically active since her 2016 article, working for the Obama administration and now under Biden.

In alignment with Biden’s view of Bork’s “misguided philosophy,” Khan will challenge the standards that Bork has deeply instilled in antitrust enforcement. As she explains in a New York Times article, “These are new technologies and new business models.” “The remedy is new thinking that is informed by traditional principles.”

Yet, Robert Bork provided these “traditional principles”; he gave antitrust an economic mechanism ‒ legs to stand on. This was a dramatic change. Khan, however, has not (yet) contributed the same revolutionary change. At the moment, albeit only at age 32, she offers explanations and recommendations for how to employ more thorough economic analysis that will more truly protect the consumer. For Khan, the resolution means breaking up big business to improve inequality and social problems, encourage private investment, and protect democracy. But for Bork, the solution at the time meant removing government barriers and providing an economic standard that aims to serve the consumer. Their main difference? Bork believed that the government was inefficient whereas Khan thinks that government is needed to address the current issues in big tech. Will they be equally influential? Bork’s got a start and an economic theory, but Khan may continue to shake things up.

Featured Image Source: Financial Times

Comments are closed.