As Elizabeth Holmes’ company, Theranos, came crashing down around her ears, NPR writer Sydell penned an article that asked “Is There A Double Standard When Female CEOs In Tech Stumble?” The article cited Holmes as one example of potentially disproportionately targeted female CEOs. Sydell was not alone in her concern: The New York Times published an article by former Reddit CEO Ellen Pao which argued that “it can be sexist to hold [Holmes] accountable for alleged serious wrongdoing and not hold an array of men accountable for reports of wrongdoing or bad judgment.”

Holmes stands accused of running a company which knowingly provided fraudulent blood test results to thousands of patients. These patients sought life-and-death diagnoses relating to miscarriages, cancer, and strokes, and, according to prosecutors, Holmes’ company knowingly gave them inaccurate results. Calling her alleged crimes a “stumble” or an instance of “bad judgement” utterly fails to convey the gravity of her alleged transgressions and offers an insultingly dismissive judgement of the devastation Theranos caused. Furthermore, attributing her prosecution or public disdain for the company to sexism makes a mockery of the myriad of very justified criticisms of sexism in tech.

The Rise and Fall of Theranos

Theranos based its company’s promise on a deceptively simple concept: blood testing that could be conducted with a very small amount of blood, obtained through a prick of the finger, instead of the traditional vials of blood drawn from veins. This method was allegedly faster, cheaper, and less invasive than traditional methods of drawing larger quantities of blood from veins.

However, due to whistleblowers like Tyler Schultz and Erika Cheung and investigative journalism largely conducted by the Wall Street Journal, Theranos’s rosy appearance ultimately crumbled. Whistleblowers alleged that Theranos had been dishonest about its testing procedures, that the procedures were dangerously inaccurate, and that the company had lied about its revenue.

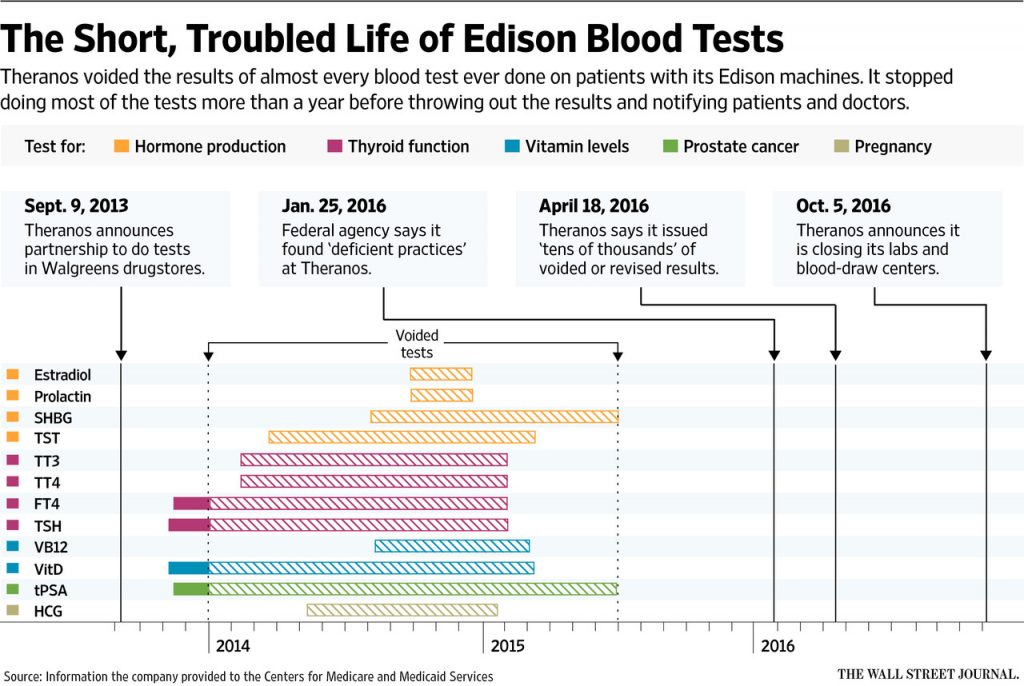

Theranos produced its own machines, called “Edison” machines. Theranos claimed these machines represented a massive technological breakthrough and were the main pillar of their testing methods and procedure. However, whistleblowers cast into question both the machines’ alleged primary role in testing and their quality.

At first, Holmes allegedly claimed the Edisons could run 200+ tests simultaneously, later revising her estimate down to approximately 70 simultaneous tests. When Schultz spoke publicly about the company, he revealed that the machines could actually run only one test at a time. Consequently, while Holmes allegedly claimed that the Edisons ran the company’s tests, in reality, many of the tests did not actually run on Theranos-produced machines, but instead on machines made by other companies like Tecan that Theranos had only modified.

Furthermore, the Edison machines which were used did not resemble the quality Holmes described. Schultz told reporters that these Edison machines suffered from critical design flaws, including doors he had to tape shut, malfunctioning barcode scanners, improperly secured pipettes, and a very narrow functional temperature range.

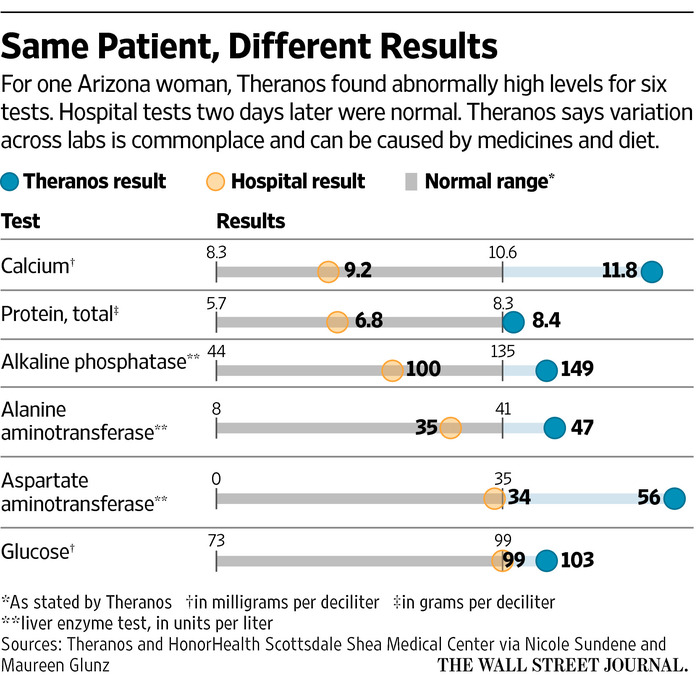

These machines’ flaws were not only aesthetic or time-consuming to repair: the resulting tests were frequently and critically inaccurate. Schultz, who ultimately left the company due to his discovery that their syphilis test was frequently incorrect, noted that “every single scientist there thought the whole thing was [fake].” An inspection of the devices revealed that 29% of the test results received a “red flag” indicating a possible inaccuracy, and of that 29%, more than 80% of those possible accuracies were at least three standard deviations from the expected number, suggesting these results were extremely questionable. When the company was supposed to undergo a standard form of “proficiency testing,” the company cheated on the government tests. They conducted their tests on different machines than they used to test patient samples, using non-Edison machines for their quality check but Edisons to conduct equivalent patient tests. Shulman, director of the evaluation program, stated that this discrepancy is a “violation of the state and federal requirements,” which mandate that the procedures used when testing the machines match the procedures used to carry out patient tests. They also threw out “outlier” data points arbitrarily to improve the average results.

These failed tests altered people’s lives in irreversible ways. One man, Steve Hammons, relied on Theranos coagulation tests to track his administration of a blood-thinning medication. These tests were absolutely critical for Hammons, who was at risk of either a dangerous bleed or a stroke if the medicine was over-or under-administered. At least one of his Theranos results were inaccurate, and he ultimately underwent heart surgery to drain excess blood from the heart cavity. Theranos only notified him of their error two months after Hammons received the initial erroneous diagnosis. Theranos eventually “voided” eleven months of the blood coagulation tests after admitting that many people, like Hammons, may have received false results. One patient told a doctor that he had experienced “skin bruising” and didn’t “fe[el] right” after following Theranos test results regarding the blood medication administration.

| Image Source: Wall Street Journal

Multiple patients received erroneous diabetes tests that incorrectly suggested they be placed on serious medication to treat diabetes despite not having diabetes. This medication can cause muscle pain, vomiting, diarrhea, and respiratory problems. Ms. Sheri Ackert, a breast cancer survivor, received an inaccurate Theranos hormone test suggesting her cancer had returned even after her double mastectomy. Ackert ultimately learned—from a different company’s test—that her hormone levels were less than 0.6% of Theranos’s measurement, indicating no breast cancer. One Theranos employee recounted tests of potassium levels that would, if correct, indicate a healthy patient was currently dead. Patients received false positives for prostate cancer and for HIV.

Brittany Gould, a woman who had previously suffered three miscarriages, recieved a Theranos test indicating that she would soon experience her fourth miscarriage. Ms. Gould, devastated, told her seven-year-old daughter “Mommy is not having a baby,” and discussed options with her doctor to terminate the pregnancy rather than suffer through a fourth miscarriage. However, another company’s test proved the Theranos test wrong, and Ms. Gould gave birth to a baby girl several months later.

In addition to alleged dishonesty about the company’s products and their accuracy, the prosecution has accused Holmes of knowingly lying about the company’s revenues, telling investors that the company would make $100 million in revenue in 2014 and $1 billion in revenue in 2015, while the company generated only minimal revenue in both years. Furthermore, Holmes allegedly told investors that Theranos had lucrative military contracts and that the US Armed Forces used Theranos technology in combat conditions (the military used no Theranos technology) and that Theranos Wellness Centers in Walgreens were planned to increase (they were planned to decrease). Under oath, Holmes admitted to using Pfizer’s company logo without their permission on Theranos documents that Pfizer had not even read.

Who Is on Trial, and for What?

Elizabeth Holmes is on trial alongside Sunny Balwani, former president of Theranos and Holmes’ ex-boyfriend. Both Holmes and Balwani face the same charges, but, due to Holmes’ intent to blame her behavior in part on Balwani’s alleged deception and abuse, their legal battles have been split into two separate trials.

Holmes stands accused of multiple counts of wire fraud and conspiracy to commit wire fraud, charges which reflect her alleged intentional deceptions for the purposes of convincing people to transfer funds to her and her company. The emotional and medical damages caused to patients by the false tests is the subject of pending civil litigation, while the criminal litigation focuses on the financial damages to investors or patients who paid Theranos directly for their tests. For Holmes to be convicted, prosecutors must demonstrate that Holmes knew the statements that she made were false at the time she made them. If she genuinely believed that her statements were accurate and that her company was just as revolutionary and successful as she claimed, then she has committed no crime—even if those statements were ultimately proven false.

Holmes’ trial is ongoing, but prosecutors so far have presented testimony from Theranos employees and investors alike about their interactions with Holmes, alongside internal company emails. A former employee, Gangakhedkar, told the court that, “[w]e were aware there were reliability issues” with the critical tests and claimed Holmes was aware of the tests’ problems but urged their distribution to Walgreens stores regardless. In 2014, Christian Holmes, Holmes’ brother and Theranos employee, told his sister via email that “there seem to be issues with [the tests’] accuracy,” to which Holmes responded that she “obviously … can’t tell [the doctors] we are wrong.”

A Dr. Rosendorff at the company complained about inaccurate hCG tests (a pregnancy hormone test) and instructed the company to stop using them. The testing continued without Dr. Rosendorff’s knowledge after other employees removed him from the relevant email chains. In 2015, Balwani sent Holmes an email claiming that the company was “without solid substance” and chemistry teams had “no product coming out,” to which Homes replied, “I know.” Balwani sent Holmes multiple texts indicating that he was concerned that the company was not accurately representing its testing capability, which Holmes agreed in court were “open” about his concerns that Theranos lacked substance.

Holmes’ defense team argues that Holmes genuinely believed the statements she made about Theranos, and that her relationship with Balwani was sexually and emotionally abusive, which seriously compromised her judgement and her ability to understand the true flaws in Theranos. While Holmes stated in court that Balwani did not force her to make any statements to journalists or investors or control her actions with the Board or other companies, she did indicate that he “impacted everything about who I was” while they were romantically involved. Balwani’s attorney denied these allegations, but if the jury finds them credible, any coercion, abuse, or deception between Balwani and Holmes can contribute to the ultimate conclusion of whether or not Holmes was intentionally dishonest.

Holmes as a “Feminist” Symbol

As the Holmes trial continues, commentators like Ellen Pao have repeatedly broached the idea that Holmes is being punished while other tech company CEOs with comparable behavior go unreproached, a form of insidious sexism. Pao in particular cites WeWork, Uber, and Facebook as examples of tech companies with scandals involving money, ethics, or both, and notes that these CEOs (all male) did not face “significant legal consequences.” Pao also cites Musk, claiming that Musk got his “hand slapped” when the Securities and Exchange Commission banned him from posting on Twitter without lawyer approval due to allegations of fraudulent Tweets. That Holmes faces prison, but Neumann, Kalanick, Zuckerberg, and Musk do not, reflects sexism, according to Pao.

These comparisons are irrelevant, misleading, and insulting. Not one of these CEOs stands accused of the same crimes and endangerment as Holmes. Pao claims that Neumann and Kalanick “hyped their way into raising over $10 billion” by claiming that they would “disrupt their stagnant, tired industries.” This criticism isn’t untrue, and it’s perfectly reasonable to want Neumann and Kalanick held accountable for any unethical or discriminatory behavior that occurred. However, claiming that these actions are somehow equivalent to Holmes’ alleged actions simply isn’t true. Holmes is on trial for allegedly claiming her company produced technology with capabilities it simply didn’t have and allegedly knowingly selling defunct technology, not just for bombastic marketing rhetoric. To serve as a compelling equivalent, Kalanick would have had to promise that the Uber app would allow people to summon cars to pick them up and drive them from one predetermined location to another, only to later reveal that many of the drivers didn’t use the app at all, that those who did use the app could only accurately determine the location a fraction of the time, and that passengers had routinely been tossed out of cars in actively dangerous locations.

In short, Kalanick would have had to market a product that he knew didn’t work as a fully functional product to the detriment of investors’ money and clients’ health. The Uber app, however, is a functioning product, which does exactly what Kalanick claimed it did when he made that claim. Zuckerberg’s Facebook is indeed a functional website. Musk does produce cars. While these men deserve their fair share of criticism and investigation of any credible allegations against them, comparing them to Holmes in order to discuss alleged sexism is not meaningful or relevant: their situations are so profoundly different. Comparing them to Holmes would be as bizarre as comparing Lori Loughlin’s conviction to the acquittal of a man accused of murder to declare one outcome is sexist: the cases do not involve the same crime or circumstances.

However, there is a man involved in circumstances that are comparable to Holmes. His name is Sunny Balwani, ex-president of Theranos, and his trial will begin very soon, for all the same charges as Holmes. He’s also a man in tech, and Pao claimed that the “boy’s club[…]supports and protects its own,” so surely, if Holmes’ punishment is partially due to gender, Balwani would be treated more gently. In fact, since Balwani allegedly participated in equally criminal actions, he’s subject to equal criminal charges and faces the same possible jail sentence.

When Erika Cheung, Theranos whistleblower, spoke to StatNews, she too brought up other instances of deception and fraud committed by men, specifically, Billy McFarland, who swindled people out of money by creating a phony music festival and received at least five years in prison. Cheung claimed that Holmes “endangered the lives of tens of thousands of patients,” and when her interviewer asked about jail time, Cheung replied, “[d]efinitely more, I suppose, than the Fyre Festival guy.”

The jury must decide what portion of the deception is owed to Holmes, and what to Balwani: Holmes’ lawyers have yet to fully present their case regarding accusations that Balwani abused Holmes, and that case may prove compelling. However, to smugly claim a company that allegedly built thousands of false medical tests and nonexistent technology is only suffering consequences because the CEO was female is asinine and insulting—both to Theranos’s many victims and to the many women in tech who do suffer from sexist assumptions and double standards.

Featured Image Source: Ethan Pines/The Forbes Collection

Comments are closed.