The year-long conflict in Ethiopia’s northern region of Tigray has ushered in one of the worst humanitarian crises in the world. Through it all—killings, looting, sexual violence, and displacement—civilians continue to pay the high price for the descent of the second-most populous country in Africa into ethnopolitical confrontations and mass starvation. In November 2020, tensions between Ethiopia’s former dominant political force, the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), and the central government in Addis Ababa came to a head when Prime Minister Abiy Ahmed postponed elections during the pandemic amidst a series of reforms seen as curbing TPLF’s power. The protracted conflict involved the presence of Eritrean troops fighting alongside the government which engulfed the country in waves of mass atrocities, displacing two million Ethiopians, and driving a further 400,000 into famine. The disastrous conditions faced by the population are all the more intolerable because Tigray’s famine is caused entirely by war. It meets the criteria of the 2018 UN Security Council Resolution on starvation in the context of armed conflict that recognizes famines as “man-made disasters.” The resolution was key in reflecting the changing nature of armed conflicts in Africa where countries like Yemen, Syria, Somalia, and South Sudan faced similar conflict-induced human tragedies.

But the conflict is not only one of arms and destruction; it is one of metanarratives and information dissemination. The government’s tightening grip on telecommunications, the internet, and banking services led to a state-sanctioned communications blackout which deepened the rift between the country and the rest of the world. Journalistic efforts to report on the atrocities taking place are systematically and strategically suppressed. Last November, the government announced new restrictions on the dissemination of information about the war, prohibiting unauthorized news media to report on military maneuvers and battlefront updates. This has resulted in a partisan ecosystem of information where dualist constructions of the other shape identity formation along essentialized ethnic lines and “with us or against us” narrative. Ethiopia is a historically multiethnic and multilinguistic country that hosts more than 80 ethnicities; tribal politics and narrative constructions of Ethiopia’s optimal framework for governance are reflective of a rhetorical war that was fought long before the outbreak of hostilities in 2020. While Tigray leaders believe a federal system that leaves substantial autonomy to different local communities to be the best avenue to grapple with Ethiopia’s multiethnic legacy, Abiy Ahmed and proponents of centralism defend the notion of a unified state around a central government in Addis Ababa to eradicate inter-ethnic conflicts.

The dynamics of the conflict in Ethiopia have changed recently. The TPLF retreated to Tigray and federal troops have not moved further into the region, leaving room for dialogue and more consequential talks. However, the humanitarian crisis in the region of Tigray is dire, and claims have surfaced that the government in Addis Ababa is deliberately starving the people in Tigray, blocking humanitarian relief, and arbitrarily detaining human rights activists, journalists, and ethnic Tigrayan Ethiopians. According to the UN, a “de facto humanitarian blockade“ puts millions on the brink of famine while preventing aid from breaking through. In light of Ethiopia’s contentious ethnic politics, the ‘pan-Ethiopian’ metanarratives advanced by Abiy Ahmed’s government legitimized driving the population towards mass starvation and blocking humanitarian assistance under the guise of fighting an insurgency in the North. The government’s designation of the TPLF as a terrorist organization and Abiy Ahmed’s promise to “bury the enemy with [their] blood and bones“ illustrates the government’s efforts to capitalize on false flag threats to consolidate his political base. Abiy Ahmed’s landslide victory in the 2021 elections further confirms the federal government’s political strategy.

Amidst human suffering and rhetorical warfare, the brutalities targeting religious leaders, holy places, and heritage in Tigray juxtapose the distinctly ethnopolitical character of the conflict with noticeable religious dimensions. Digging deeper into the role of religious institutions and actors reveals that religion has been co-opted by ethnonationalist rhetoric. The highly partisan dissemination of information within the country creates an environment in which those who speak on the issue are immediately categorized, and the breakthrough of voices of religious authority from faith leaders is hampered. This process exacerbates ethnic divides and consequently, politicizes religious actors that may have otherwise reinforced the nation’s social fiber and consolidated peace. Hence, while religion has historically provided a framework for peaceful cohabitation throughout Ethiopian history, it became a serious source of polarization in the current conflict. The head of the Orthodox Church, of Tigrayan descent, denounced the actions of the government and spoke against the violence. Other clergy members, however, including the top religious leaders making up the country’s reconciliation commission, unequivocally support the government’s actions. Elsewhere, the Eritrean Catholic bishops, just like the independent Eritrean Orthodox Church of North America, Europe, and the Middle East, have called for the end of hostilities.

Despite the potential of religion to easily shift from brokering peace to polarizing pre-existing ethnic divides, one can hope that the shift can be reversed and religious actors’ politicization may need not be indefinite. Finding a unified narrative is necessary to redefine religion’s role in the conflict, away from perpetrating violence to calling for peace. In effect, empowering the voices among Ethiopia’s religious community that are calling for a de-escalation of the conflict provides a pathway to peace as it would frame the lifting of the humanitarian blockade as a bipartisan beneficial issue. The Catholic Eparchy of Adigrat’s reiterated call for dialogue and unhindered humanitarian aid in Tigray coincides with growing international pressure from the global church and faith-based organizations to prevent “irreparable disaster on human lives”—and indicates some religious actors’ courage to speak truth to power.

As Tigray’s crisis is heading to a tragic fate, concerns are that a full-fledged civil war in what was once a linchpin of regional security would also destabilize the Horn of Africa should it spill outside Ethiopia’s borders. Adding to that are mounting implications for NGOs trying to provide humanitarian assistance to victims of famine in times of conflict. Ethiopia joins Nigeria, South Sudan, and Yemen as the world’s worst hunger hotspots putting tens of millions at risk of acute food insecurity, and in doing so, also sheds light on the use of starvation as a weapon of war. “Famine does not arrive suddenly or unexpectedly… it is a slow agonizing process, driven by callous national politics and international indifference,” said Oxfam’s deputy humanitarian director. The face of modern famine urges us to frame it as a global peace and security concern; the intersection between Ethiopia’s highly partisan information ecosystem and the politicization of religious actors along ethnic lines alternatively offers lenses to be in a position to read, understand and build bridges over the religious and political divides.

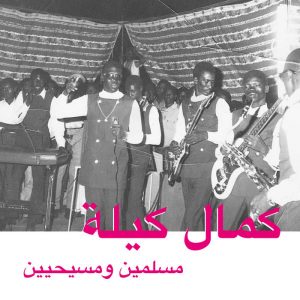

Featured Image Source: Associated Press, Mulugeta Ayene

Comments are closed.