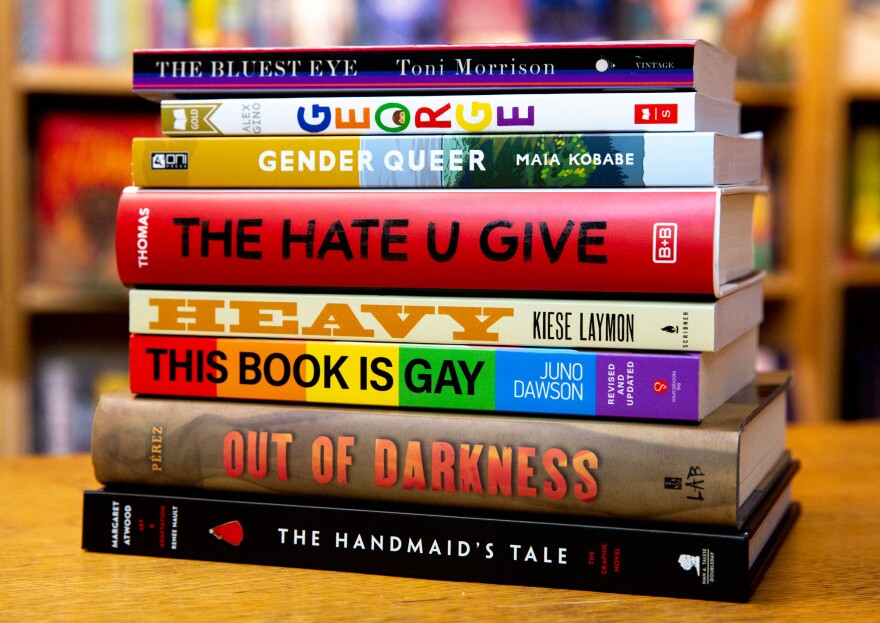

Toni Morrison’s first published novel The Bluest Eye tells the story of Pecola, a young Black girl living in the wake of the Great Depression who yearns for blue eyes and blonde hair, as she believes that her blackness makes her ugly. The story touches on an array of themes, including domestic violence, incest, rape, infant mortality, alcoholism and racism. The novel, which is known for jump-starting Morrison’s literary career, is now also known for its addition to the growing list of banned books in the United States that highlight race and sexuality.

In a 4-3 vote, the Wentzville School Board of Missouri voted to ban the novel. “By all means, go buy the book for your child,” said Wentzville school board member Sandy Garber, who claimed they were concerned with protecting children from obscenity. “But I would not want this book in the school for anyone else to see.”

Interestingly enough, the late Toni Morrison spoke of book banning in relation to Mark Twain’s iconic book The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, stating that “the brilliance of Huckleberry Finn is in [the] argument it raises.” Further, she mentions that calls to ban this book were “a purist yet elementary kind of censorship designed to appease adults rather than educate children.”

In a perfect education system, teachers would be allowed to select books that will resonate with their students and their classes’ curriculum. However, with a deeply politically polarized nation and fervor over critical race theory, teachers are anticipating challenges to any book that discusses race or features characters of color.

The ongoing critical race theory debate

Critical race theory has been one of many dominating debates in recent news cycles. According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, critical race theory is defined as “a group of concepts (such as the idea that race is a sociological rather than biological designation, and that racism pervades society and is fostered and perpetuated by the legal system) used for examining the relationship between race and the laws and legal institutions of a country and especially the United States.”

Therefore, critical race theory challenges the American ideal of racism as an individual trait adopted by certain people. Instead, it shows racism to be a systemic and institutional issue—the backlash primarily stems from this idea.

Critical race theory’s main argument is summed up by Mari Matusda, a law professor at the University of Hawaii who was an early developer of critical race theory: “The problem is not bad people, the problem is a system that reproduces bad outcomes. It is both humane and inclusive to say, ‘We have done things that have hurt all of us, and we need to find a way out.”

After the mass protests following the killing of George Floyd in 2020 that sparked conversations on structural racism in the United States, President Donald Trump issued a memo to federal agencies warning against the “divisive training sessions” related to critical race theory. This was soon followed by an executive order that barred any training suggesting that the United States was fundamentally racist or explored gender, race or sexuality based harassment.

Months later the Biden administration revoked this order, yet the damage had been done, and critical race theory was already made into a wedge issue. State’s legislatures with a Republican majority have made a plethora of attempts, many successful, to implement similar bans of these teachings, with public schools being the foreground of the battle.

“The woke class wants to teach kids to hate each other, rather than teaching them how to read, but we will not let them bring nonsense ideology into Florida’s schools,” said Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida. He then went on to call critical race theory “state-sanctioned racism”.

Professor Kimberle Williams Crenshaw, who is noted for coining the term, acknowledged that this is a long-standing tactic that opponents of race based teachings have used—insisting that recognizing racism is itself racist. “The rhetoric allows for racial equity laws, demands and movements to be framed as aggression and discrimination against white people,” she said. That, she added, is at odds with what critical race theorists have been saying for four decades.

“New” focus on public education

So, as a result of fervor over critical race theory and the way history is being taught in our public schools, book banning is back.

In Texas, Republican state representative Matt Krause banned 850 books, with many of them dealing with issues surrounding race, gender and sexuality issues. While this is certainly a bold move, political observers in Texas have noted that Krause is locked in a crowded primary race for Attorney General. By raising this issue, Krause is also raising his profile to potential voters and political allies. As University of Houston political science professor Brian Rottinghaus stated, “He’s not well known statewide, and so he needs to put down a pretty tall conservative flag to get notice,” Rottinghaus said. “As a political statement, it certainly conveys the clear message that the Republicans are watching.”

While the banning of books in public schools certainly is a recurring theme of American politics, it is an incredibly effective wedge issue.

Wedge issues are not a new trend in American politics—taking political advantage of rifts centered around ethnicity, religion, social class and other markers of identity can often result in political movements that spark outrage all the way from the streets to the ballot box.

Politics centered around these issues are not concerned with changing people’s minds, rather getting people to form opinions on topics they haven’t really thought about. “Candidates don’t think they can get you to be pro-choice if you’ve been pro-life your whole life,” D. Sunshine Hillygus, author of the book The Persuadable Voter: Wedge Issues in Presidential Campaigns, said. “What candidates or parties attempt to do is manipulate the salience of a divisive issue as a way to change the likelihood that people will make a decision on the basis of it.” Therefore, an issue that some had not really developed an opinion on is suddenly framed and broadcasted in a way that makes it one of the most notable topics of an election year.

This is where the book-banning debate lies currently. Although the vast majority of Americans oppose and find efforts to remove books from schools, libraries or universities to be harmful, there has been an incredibly vocal pushback by conservative groups and parents, promoted by Republican lawmakers, to restrict access to books they deem objectionable.

The impacts of these decisions

The Republican Party’s view of “patriotic education” makes clear that educational practices that inform and address systemic problems are both a threat to its politics and a deserving of disdain. This decision to deny young people this knowledge of history and identity is deliberately harmful. Teaching young people about the history of the United States, which is deeply rooted in colonization and slavery is not “Anti-American.” Rather, it is necessary to have conversations and calls to action amongst individuals and institutions that bring attention to recurring issues whose origins can be found in hundreds of years of history.

Republican legislators now use the law to turn public education into white nationalist factories and spaces of ignorance and conformity. Republican state legislators have put these policies into place which erase truthful history and attack any reference to race, diversity and equity while also undermining teachers and their attempts to exercise control over their curriculum and the knowledge they work to impart onto their students.

Horrified over the possibility of young people learning about the history of colonization, slavery and the struggles of those who have resisted long-standing forms of oppression, many of these politicians have subscribed to politics of denial and disappearance.

Featured image source: St. Louis Public Radio, NPR

Comments are closed.