——— History of Things ———

Any decent murder mystery should begin with a dead body in the woods. That’s how this one starts.

In 1994, park scouts shot a man dead in the empty woodlands of North Luangwa National Park, a Zambian nature preserve about the size of Delaware. Squadrons wielded their rifles at the man and his fleeing accomplice, giving way to a slathering of blurred gunfire and incoherent blasts. When the dust settled, a human being lay lifeless. Several months later, ABC televised the murder in an hour-long special. As footage of the man’s death rolls, host Meredith Vieira explains that he and his friend are suspected elephant hunters, thwarting North Luangwa’s emergence from a decades’ long poaching epidemic. Suddenly, the park scouts open fire on the unknown man, and Vieria laments in voiceover: “Conservation. Morality. Africa.”

The program premiered on American televisions with the lack of fanfare typical for most cable news specials, but when a tape of the special arrived in Zambia, government officials had an emphatically different reaction.

They shouted at the program, fuming at its backwards depiction of Zambia as a lawless frontier. Though some African countries did have shoot-on-site policies against poachers, Zambian scouts (the equivalent of American park rangers) could only brandish firearms in self-defense. National police opened a homicide investigation and descended onto the park in droves. Swarming the remote Luangwa Valley wilderness, the investigators searched for their prime suspects: an American couple — environmentalists — Mark and Delia Owens.

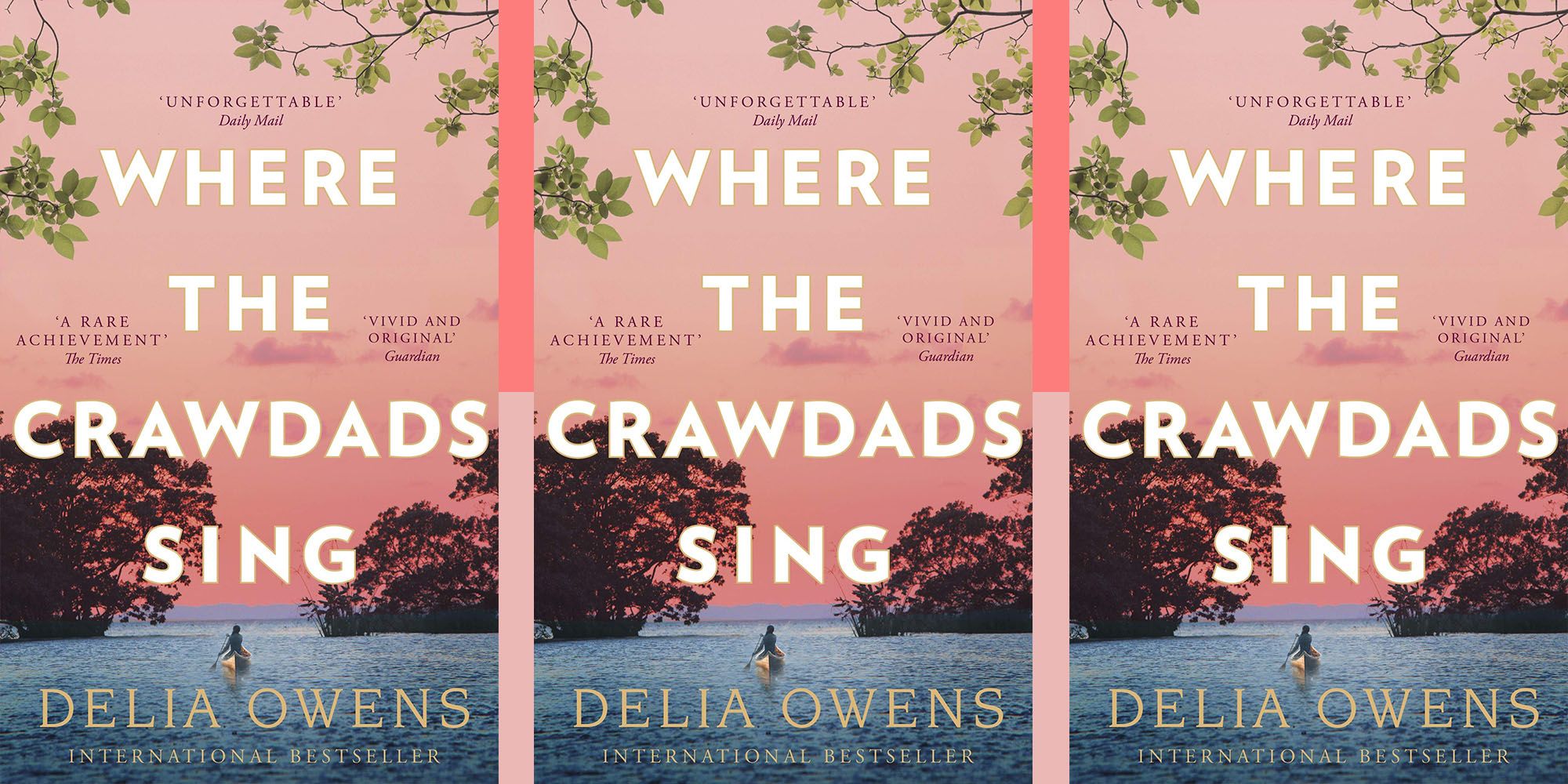

If, in the past few years, you’ve wandered into a bookstore or supermarket or really anywhere that sells books, you’ve probably seen Delia Owens’s name. You know where— those big letters, that pastel pink cover, and that ever so implausible destination: Where the (famously songless) Crawdads Sing. My mother got her copy in a Portland bookstore. A friend bought their own through an Asian supplier. I found mine in the aisles of an East London Tesco. Owens’s 2018 fiction debut is a global phenomenon, dominating the New York Times Best Sellers list (it holds the record for most weeks at #1) and charting as the third top-selling book on Amazon in 2021, three whole years after its release. Elizabeth Warren has described the book as “lyrical,” while Reese Witherspoon bestowed on it the honor of an official book club choice. This year, Witherspoon is set to continue championing Crawdads’ popularity, producing a film adaptation set for a July release, whose trailer already has over 6 million Youtube views.

Crawdads is decades in the making. “I think it was seeing lions and elephants every single day that I started realizing how similar our behavior is to wildlife,” Owens told a reporter, “I could see us in them.” She and her ex-husband Mark Owens spent most of their adulthood enmeshed in African conservation. While Crawdads is Owens’s first novel, she and Mark co-authored three previous memoirs, starting with their 1984 international bestseller, Cry of the Kalahari, a stirring account of their time in Botswana’s Kalahari Desert.

The book refashioned the Owenses as wilderness ambassadors in the vein of Jane Goodall and Dian Fossey, guiding their American audiences through the low-lying African bush with straightforward, easy-to-understand language. After protesting the corporate-backed blockage of a wildebeest migration route, the Owenses became African pariahs and, quickly, Botswanan deportees. In exile from the Kalahari, the Owenses discovered an idyllic alternative: North Luangwa National Park, a patch of earthen savanna tucked in the furthest, most remote corner of Zambia’s Northern Province.

Where the Crawdads Sing is coming to theaters this July, with Normal People‘s Daisy Edgar-Jones starring as the lead character Kya, a marsh-dwelling woman who gets implicated in the murder of an ex-lover. | Image Source: Good House Keeping

Where the Crawdads Sing is coming to theaters this July, with Normal People‘s Daisy Edgar-Jones starring as the lead character Kya, a marsh-dwelling woman who gets implicated in the murder of an ex-lover. | Image Source: Good House Keeping

The Owenses arrived in Zambia during the presidency of Kenneth Kaunda, a man whose shadow still looms large over the landlocked nation.

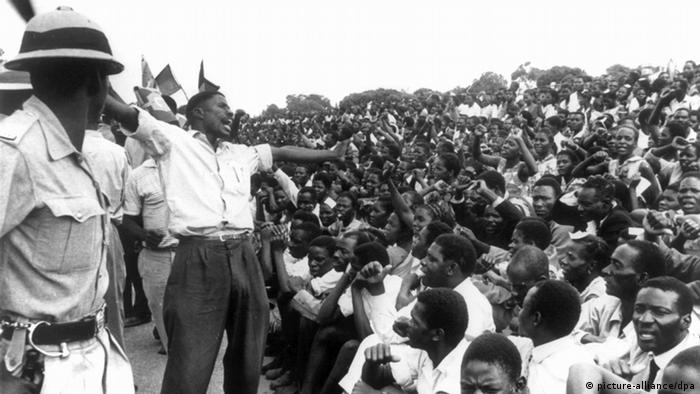

Kaunda became a household name in the 1950s, during Zambia’s fight for independence. At the time, North Rhodesia’s white-minority government (established by England) openly advocated white supremacy and segregation, depriving Black citizens of the most basic dignities. Kaunda wouldn’t have it. With a sermon of Gandhian nonviolence, he headed a series of national protests culminating in a 1958 boycott of Rhodesia’s sham elections. In response, the authorities jailed Kaunda and banned his Black-majority party. Kaunda described his incarceration as his “most difficult months,” but, like a blade tempered by flame, he emerged from prison even stronger. After Kaunda’s release in 1960, he became the singular face of Zambian independence, championing the struggle for civil rights. And he won.

In 1964, Northern Rhodesia held its first elections with interracial voting. Kaunda, running under the United National Independence Party (UNIP), was swept to office in a landslide. Overnight, white supremacist Rhodesia became post-colonial Zambia.

After independence, his presidency wavered as ethnic blocs splintered into their own political parties, threatening to shatter Kaunda’s delicate grasp on power. Kaunda’s UNIP broke in two, his former vice president leading an ethnic faction that posed a strong challenge at the ballot box. Too strong. In February 1972, Kaunda banned the breakaway party and detained his former vice president and over 100 other political dissidents. That December, he passed a constitutional amendment making Zambia a de jure one-party state.

Despite Kaunda’s totalitarian shift, he maintained broad popularity, a symptom of Zambia’s soaring copper wealth.

Copper is Zambia’s life blood. One of the largest copper deposits in the world lies on the border between Zambia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and ever since mining first began in 1928, mineral wealth has been the region’s economic backbone. To this day, Zambia’s GDP is inextricably tied to global copper prices.

In the late 1960s, these international prices were high — sky high — stimulating never-before-seen growth in Zambia’s mining sector. By 1969, Zambia had been reclassified as a middle-income country and Zambia’s GDP, which copper accounted for nearly 30% of, was one of the highest in Africa. Zambia had achieved stable economic development, but Kaunda had greater ambitions.

In 1969, concerned that corporate mines had reduced investment since Rhodesia’s collapse, Kaunda nationalized all privately-owned copper mines into a state-run system. Under this model, mineral profits would be reinvested into social services like healthcare, education, and infrastructure. Kaunda envisioned a country where copper mines not only funded government programs but provided a range of utilities themselves — from roads and housing to community bars, kitchens and social clubs. Spurred by mineral wealth, Zambia entered a golden age of popular well-being.

During Mark and Delia Owens’s early days in North Luangwa, as they drove through a wooded savanna, their truck stopped near a leadwood thicket. As it stalled, the couple glanced at the ground and saw five ash-white elephant skulls. Soon they noticed pelvises, ribs, and whole skeletons scattered across the soil. “We are standing in the midst of a killing field,” Mark wrote in the Owenses’ 1992 book The Eye of the Elephant, “Although we have not yet run into poachers it must be only a matter of time until we do…If we stay here to work, we will have to do something about them.”

Conservationists had been trying “to do something” about poachers long before the Owenses stepped foot in Zambia. In 1983, a group of wildlife managers, government officials, and international donors met at the Luangwa-adjacent Lupande Lodge to discuss solutions for the poaching influx. This meeting, in the words of one historian, “changed the face of Zambian conservation…for the next decade.”

While attendees agreed to integrate both international actors and local communities in their conservation efforts, two disparate factions emerged. On one side, a band of European-led NGOs urged the implementation of a large-scale project that would have granted international actors a substantial role in park management. On the other side, the Zambian National Parks and Wildlife Service (NPWS) urged a reinvigoration of existing institutions. Rangers needed proper funding and shielding against crooked politicians who often dipped into department pocketbooks. The NPWS made a bigger ask though: that tourism revenue be split with local communities.

Their proposal reflected a mode of conservation whereby legal claims over plants and wildlife are transferred to local communities who can then establish rights for tourism and profit off their conservation policies. Such communal approaches to wildlife management would go on to have a largely successful track record, but, at the time, the Europeans weren’t too keen on it. Though the NGOs paid lip-service to revenue-sharing, in their 90-page mission statement they didn’t mention it once. From the NPWS’s perspective, it looked like the European philanthropists wanted to steal autonomy of Zambia’s wilderness from actual Zambians, and it increasingly seemed like this might happen, especially as the Europeans gained presidential support.

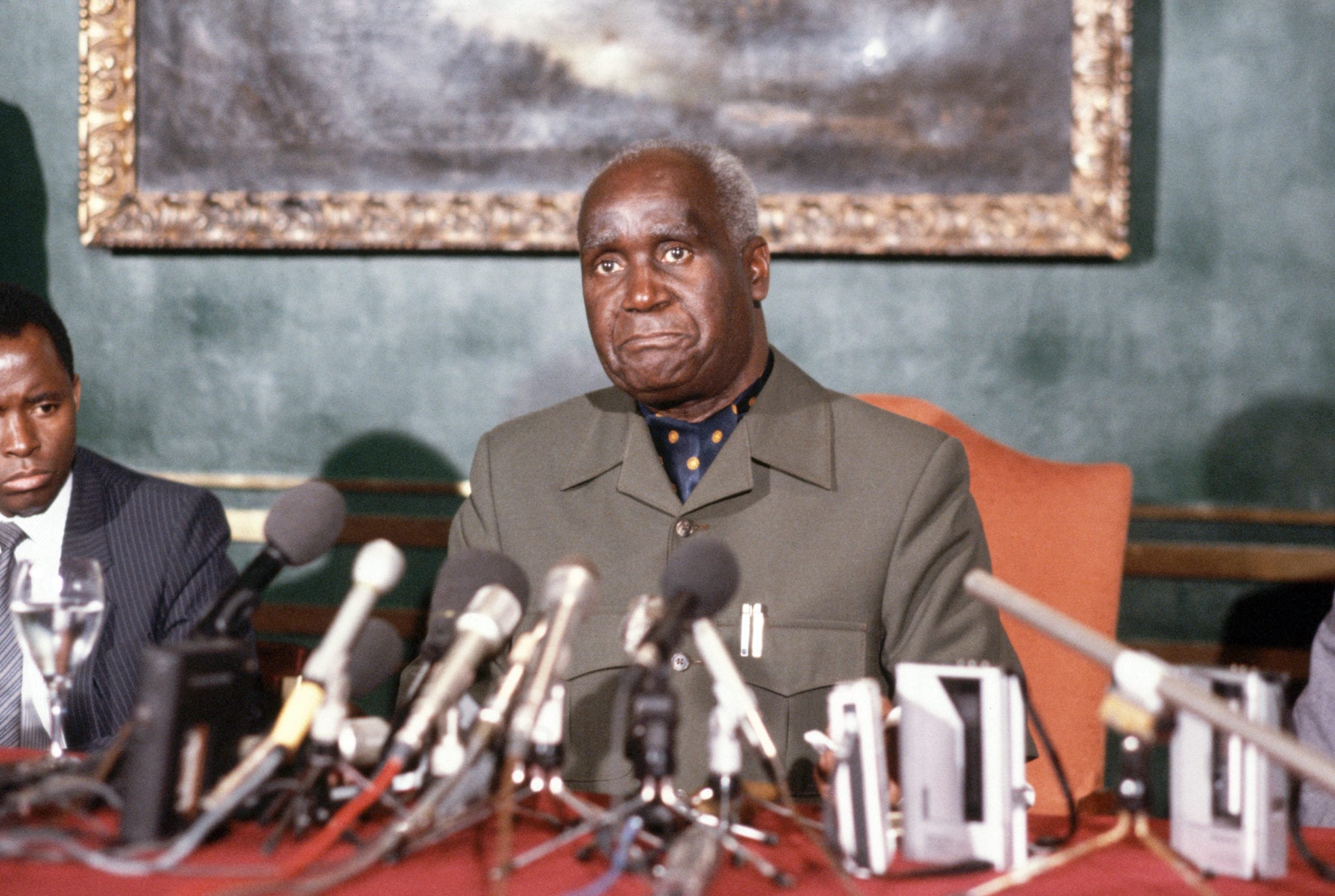

Kenneth Kaunda wasn’t your typical dictator. Sure, he censored the press, routinely jailed dissidents and his political opponents had a tendency to die under dubious circumstances, but compared to the violent regimes of other African autocrats, like Daniel Moi and Robert Mugabe, Kaunda was benign.

He led with a self-defined “African Humanism.” Where Stalin fought for the proletariat and Mao for the rural poor, Kaunda fought for what Africans had been denied throughout colonization: dignity. “This high value of man and respect … should not be lost in the new Africa,” Kaunda declared, “However ‘modern’ and ‘advanced’ this young nation of Zambia may become, we are fiercely determined that this humanism will not be obscured.” Kaunda refused to divide and conquer along ethnic lines, insisting on a “one Zambia, one nation,” policy. While most postcolonial leaders prioritized industrial expansion over conservation, Kaunda’s respect for indigenous history made a staunch environmentalist of him.

Under British rule Zambia had no formal conservation policy, and many would’ve liked it to stay that way. The Zambian parliament opposed most conservation efforts, with legislators among the greatest violators of game quotas. In 1982, one assemblyman divulged that whenever officials visited his rural region, it “turned into a hunting camp.” Disenchanted by the corrupt politics undoing state-sponsored conservation, Kaunda turned to supporting private philanthropists, personally backing European NGOs’ plan for integrated development in the Luangwa Valley.

Though Kaunda fought against poaching, he was the problem incarnate.

Rather than invest Zambia’s copper revenue into long-term development, Kaunda used it to buy political acquiescence from miners, public workers and other beneficiaries of government services. In 1975, when world copper prices crashed, so did that giving. For the next two decades, copper prices continued to fall relative to import prices, transforming Zambia from one of the wealthiest postcolonial countries to one of the poorest. As all this unfolded, Kaunda also insisted on government pricing mechanisms that produced declining returns for small-scale farmers. The combined impact of the mineral crisis and government agricultural policy tanked Zambian incomes.

Simultaneous to the country’s economic collapse, the ascent of Middle Eastern oil and East Asian wages triggered a perfect storm.

With wallets growing thicker by the day, consumers on the Asian continent stimulated demand for ivory products, which, especially in East Asia, are falsely believed to possess vital medicinal properties. Income-deprived Zambians needed money so they supported the ivory trade.

From the late 1960s to 1989, hunters killed roughly 75% of Zambia’s elephant population. Elephants weren’t alone. In 1972, the Luangwa Valley had a black rhino population of roughly 50,000. By 1992, the valley had less than a dozen. This is what happened to the passenger pigeon and the Tasmanian tiger. This is what extinction looks like.

During this period, soldiers’ and policemen’s wages also plummeted. They had children and wives and parents and every single one of them needed to eat. So, rather than serve its citizens, Zambian law enforcement served the highest bidder. Bribery was commonplace. As a side hustle, agencies also frequently let poachers borrow and buy state-issued weapons, transport and ammunition. With extensive weapon supplies and impressive authority, law enforcement units often took to poaching themselves.

Park scouts likewise faced steep budget cuts, reduced salaries and late paychecks. With Kaunda’s government unable to pay, the NPWS became ineffective and unable to control its own employees. Lacking any serious forms of accountability, many scouts resorted to illegal hunting and trafficking.

The NPWS scouts that Mark and Delia Owens met in North Luangwa didn’t have any weapons or uniforms or direction. With only a dozen or so scouts guarding the park, a vicinity well over 4,500 acres, Mark sympathized. “Who could blame them,” he reflected, “when they said, ‘Hey, we can’t help you to go chase poachers. Are you nuts?’” Initially, the Owenses directed their conservation efforts towards securing community employment, but Mark had other ideas.

“He believes that we should get personally involved [with the NPWS] — flying patrols, airlifting scouts, going on anti-poaching foot patrols with the guards,” Delia fumed in Eye of the Elephant. She and Mark had arguments lasting entire nights, prompting Delia to even separate from him for a time. But Mark won out.

Ever supportive of philanthropists, Kaunda’s government granted the Owenses authority over North Luangwa’s NPWS units. Mark, bankrolled by wealthy American donors, gave the scouts new sleeping bags, boots and rations. He also raised their salaries and rewarded bonuses for teams that capture 5 or more poachers.

By the early ’90s, the park’s elephant population showed signs of recovery, but poaching persisted. Mark raised the stakes of operations. He expanded anti-poaching patrols and began conducting nighttime aerial surveys. Flying above, he backfired his engine at unsuspecting poaching camps and launched barrels of fireworks at them.

Mark was at war, but he was using all the wrong tactics.

Ivory poaching is a simple affair. Pachyderm-seeking hunters sneak into a still wild area, often a protected one. When they find an elephant or rhino, they shoot it, cut out its ivory and leave the rest behind.

Severin Hauenstein, a German biologist, had a gut feeling about those carcasses getting left behind. He thought they’d fall in a specific geographic pattern, with bodies scattered far from scout posts which could spot and arrest poachers. Hauenstein and his team conducted a spatial analysis of Tanzanian elephant deaths, expecting to be vindicated, but the study revealed something else entirely. For some scouts the trend followed as expected, elephants were killed far from their outposts, but for others it was the exact opposite, elephants were killed remarkably close to their outposts. Too close.

Hauenstein and his colleagues caught on. The scouts finding bodies near their stations were in league with poachers, turning a blind eye for bribes. It was the beginning of a years’ long realization for Hauenstein that wildlife conservation, a field historically dominated by discussions of land management and local agriculture, had a lot more to do with economic structures and political institutions.

In 2019, Hauenstein delved further, studying how various socioeconomic factors impact elephant poaching. In the analysis, two variables arose as statistically notable: corruption and poverty. Poaching was a money problem.

The tusks from just one elephant could be sold for more than most Africans’ annual income. For the many have-nots throughout the developing continent, elephant poaching was a vehicle of social mobility. How do you solve that?

Hauenstein’s study found how not to. Though conservationists, like the Owenses, typically responded to poaching upticks by investing in law enforcement, Hauenstein found little correlation between expanding protection and reducing poaching. While the presence of some rangers deters many poachers, investing in scouts has diminishing returns. No matter how big and intimidating a park’s law enforcement gets, it’ll never wear down the most determined poachers. As Hauenstein explains, “[it] simply isn’t practical in sites that cover ground areas in excess of small European countries.”

Most of the extensive funds allocated to scouts would be better spent on measures to stymie poverty and corruption; that’s where they’re needed.

While Mark Owens’s expansion of North Luangwa’s scouting units may account for some of the park’s poaching decline, it’s far more likely that outside events bear responsibility. Two, in particular, seem obvious culprits.

The first was the 1989 banning by the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of the international ivory trade. As soon as the ruling passed, ivory dealers and buyers fled the business en masse, plunging the price of ivory by 96%. After the agreement, Zambia followed continental trends as elephant populations rose and poaching rates fell.

The second event was national. By the 1980s, discontent with Kaunda’s regime was pervasive. A 120% rise in the price of cornmeal instigated food riots throughout Zambia’s Copperbelt, where several people died and thousands more were arrested. Kaunda clamped down on dissent, restricting civil liberties and banning strikes. Labor unions rallied against Kaunda’s UNIP, calling for a return to multiparty politics. After a failed coup attempt in 1990, Kaunda relented to domestic pressure and agreed to host free and fair elections. After losing the next election in a landslide, Kaunda quietly parted from executive office.

The regime change made two indelible impacts on Zambian conservation. First, the new government had legitimacy that Kaunda lacked. While the poaching epidemic of the ’70s and ’80s was characterized by Kaunda’s inability to effectively rule and enforce laws, the new government didn’t face those constraints. They were popularly elected, and Zambians viewed them as possessing a greater right to rule. It wasn’t a permanent solution to poaching or corruption, but it was an important step.

Second, Kaunda’s absence freed the NPWS to take a more active role. Prior to 1991, NPWS leadership had made undue efforts to avoid intervention from the ever-skeptical Kaunda. For instance, after the 1983 Lupande Development Workshop, the department followed through with its communal wildlife management plan, taking extreme steps to shield their pilot mission from Kaunda. The department hid its workers, gaslit government actors and buried their funds in secret trusts supported by under-the-table concessions from Zambia’s tourism department and later USAID.

With Kaunda out of office, the NPWS was finally free to pursue conservation without fear of inordinate backlash.

As a new era of Zambian conservation began, the Owenses lived in an old one. Mark Owens expanded his anti-poaching operations far beyond park borders. With a helicopter and a biplane, his team routinely conducted village sweeps. “The scouts raid villages all night,” Delia Owens described in The Eye of the Elephant, “[They] burst… into poachers’ huts while they sleep—and drive back to [park headquarters] in the morning, their truck loaded with suspects.”

While the Owenses viewed sweeps as an effective anti-poaching tool, residents remember them less fondly. “The scouts took the men to one side of the village, and they… beat the ones they said were poachers,” one villager remembered. Others recall the scouts breaking into houses without warrants (which in Zambia is illegal) and beating men so badly they had to be hospitalized.

Captured prisoners were cruelly punished. One of the Owenses’ former scouts recalled how detainees would sometimes be tied to stakes and left in the blistering sun all day. Another scout recounted that “Mark Owens told us that anyone with [game] meat or a weapon should have a beating.”

The Owenses’ view towards local Zambians lacked even-footed respect. In Eye of the Elephant, Delia wrote about a discussion she had with her cook, Sunday Justice (the namesake of a prison cat in Crawdads) about traveling on airplanes. “I myself always wanted to talk to someone who has flown up in the sky…,” he reportedly said, “if you fly at night, do you go close to the stars?” However, Justice doesn’t remember saying any such thing. “I always knew what an airplane was,” he told New Yorker reporter Jeffery Goldberg, “I used to fly to Lusaka all the time… as a child and as an adult.” After working for the Owenses, Justice joined Zambia’s National Air Force.

Mark and Delia Owens’s view of Africans radiated with paternalism, often taking more unsavory flavors. Mark Harvey, a safari guide in the Luangwa Valley described the Owenses’ attitude as, “Nice continent. Pity about the Africans.” The Owenses wanted to live in an Eden-like Africa, free of human presence no matter what that entailed. “Despite the ravages of AIDS and a plethora of other diseases,” a passage from Secrets of the Savanna demurred, “Africa’s populations continue to outstrip the carry capacity of the continental resource base.”

The Owenses’ resentment towards local Africans is only a symptom of a strain of prejudice prevalent throughout American environmentalism. Like older environmentalists, such as John Muir, they frame “naturalness” as a separation of humans from the environment, rather than a viable relationship between the two. This perspective especially excludes local people who have always been a part of regions’ landscapes.

The Owenses also borrow from the forefather of American conservation, Aldo Leopold, insisting that overpopulation is the root cause of most environmental problems. In reality though, affluent lifestyles in advanced economies pose a far greater risk to the environment than developing countries’ birth rates. Though population growth can hurt ecosystems, sustainable forms of development, which are more accessible than ever before in history, can dampen if not entirely prevent damage.

While the Owenses’ prejudices are leaps and miles from those of Muir and Leopold (both of whom supported eugenics), it’s unfortunate that, rather than advocate sustainable ways to work with local communities, the Owenses chose to tepidly lament the “ravages of AIDS.”

In 1992, after the publication of Eye of the Elephant, the Owenses appeared on the Tonight Show and caught the attention of Janice Tomlin, an ABC news producer who became smitten with their story. She arranged for them to participate in a documentary special titled “Deadly Game: The Mark and Delia Owens Story.” The ABC camera crew followed them everywhere, on airplanes, through savannas and in that fatal interaction with a suspected poacher.

In a 2010 New Yorker article, journalist Jeffrey Goldberg documented Mark and Delia Owenses’ case, detailing the fallout from the televised death. As authorities investigated the homicide, they faced several immediate obstacles. They had no body, no witnesses from the ABC crew and no access to the unedited footage. The Owenses weren’t in Zambia when investigators arrived at their campsite, having returned to the US on a regularly scheduled visit. In the Owenses’ absence, investigators seized their materials and equipment. The American Embassy shortly contacted the Owenses, advising them not to return.

Despite multiple appeals to the Zambian government, Mark and Delia Owens have lived in exile from North Luangwa and Africa ever since. In the immediate aftermath of their expulsion, an official from the American Embassy demurred that, “hundreds of Zambians who worked for the project must now wonder how they will feed themselves, [as] Zambia’s North Luangwa National Park once again lies open to unrestrained poaching.”

Without the Owenses, who would save the poor people of Zambia?

In 2018, poachers did not kill a single elephant in North Luangwa National Park. Instead of raids and shootouts, today’s conservationists credit a number of other factors: declining ivory demand in East Asia, rising incomes across Zambia and, more than anything else, community cooperation. The NPWS’s communal management pilot from the ’80s has evolved into a system of Game Management Areas reliant on local involvement. This system expanded nationwide through Zambia’s Wildlife Act of 2015, which mandates that local people be consulted about and benefit from hunting and tourism near their homes.

The community-based system takes aim at Hauenstein’s diagnosis of poaching’s root causes: bad economics and bad politics. The approach bolsters economic institutions, like property rights and contract law, by adding value to natural resources and sustainable practices. It also strengthens political institutions, encouraging rural Zambians to engage in state governance and community affairs. Though the benefits of profit-sharing are whittled down by government bureaucracy and poor allocation by local councils, the program is a strong step forward.

Still, threats persist. In the wake of pandemic-induced downturns, the socioeconomic factors that underlie poaching have become a renewed threat. In 2020, COVID-19 spurred Zambian poverty to its highest level in decades. The country’s economic situation is exacerbated by a continued reliance on copper (and, in our era of omnipresent technology, cobalt) that leaves Zambia at the mercy of multinational corporations and global mineral prices.

As Zambia’s economy shows warnings of backsliding, so do its institutions. Following a narrow 2016 election, President Edgar Lungu, hedged up by the IMF and other NGOs, clamped down on political dissent, suspending over 48 opposition party members and arresting their party leader on trumped up treason charges. Though Lungu has since been voted out of office, replaced by the very leader he sought to jail, the country’s score on Freedom House’s Global Freedom Index has slid considerably, from 56 in 2017 to 51 in 2022, out of 100 possible points. While the opposition’s electoral victory is a promising step in the right direction, the further removed Zambia’s government grows from the interests of Zambians, the greater the risk of poverty and corruption, and by that measure, the greater the threat to the environment.

Throughout its history, Zambia has been courted by messianic figures claiming to offer definitive solutions to existential problems: Kenneth Kaunda guaranteed ceaseless development; copper mines pledged endless prosperity; Mark and Delia Owens promised to return Zambia’s wilderness to nonexistent paradise. But as history shows, self-described saviors rarely ever are. The greatest day for Zambian conservation will be when robust and inclusive institutions grant Zambian citizens firm control of their collective destiny. Even the Owenses recognized institutions’ ecological provenance, prefacing The Eye of the Elephant with a note that, “it is only because of [Zambia’s change to democratic] government that we have the freedom to tell our story…by telling the truth, no matter how controversial, we incur a measure of personal and professional risk, but by not telling it, we all risk much, much more.”

Featured Image Source: William Campbell Photography

Comments are closed.