As the world was rocked by the tremors of Putin’s invasion of Ukraine, people across the globe were awed by reports of thousands of ordinary Russian citizens protesting against their autocratic leader’s war. That they incurred considerable risk in doing so was quickly evident as protestors were arrested and beaten by police officers, and media outlets across the globe broadcast the tenacity and courage of the protesters.

On another continent, outside of the international spotlight, protesters in Sudan are fighting a similar battle against authoritarianism.

When military dictator Omar al-Bashir was ousted from his post in 2019 after widespread resistance, it seemed for a moment that Sudan had cast off the hold of oppressive rule. A Transitionary Military Council, divided between the military and civilians, assumed executive power in his place, with Abdullah Hamdok appointed as the civilian prime minister. However, pro-military protests–criticized as being under the aegis of the military government itself and sympathetic to the old al-Basir regime–urged a military coup in October of 2021. Since then, the military has maintained an iron grip on the administration. Despite the dangers associated with standing up to those in power, protesters have gathered across cities in large numbers to demand democratic reform. Neighborhood committees and the Sudanese Professional Association (SPA) are leading the charge for democracy, united by their discontent with current military control and seeking complete civilian rule in its place.

As protesters have been assailed with tear gas, stun grenades, and bullets, at least 80 people have been killed so far. Security forces have been aggressive in their response as they target protesters with violence and arrests. There have also been accusations of sexual violence, including gang rape. Despite the military’s claims that peaceful protests are allowed, those who take to the streets face clear and severe risks. Nevertheless, the resistance continues, especially as the Sudanese economy suffers from devaluation of its currency and withdrawal of international aid. Spiking prices, limited resources and a looming hunger crisis have pushed Sudan’s people to keep up their efforts against military rule.

Although there are evident risks to continued resistance activity, these protesters remain motivated. In part, this stems from past experiences. Sudan has already established networks and organizational structures for protesters, as exemplified by the rise of the neighborhood committees. Students and youth began to organize local peaceful protests, attracting members from a wide breadth of socioeconomic classes, ethnic backgrounds, and regional affiliations. Through it all, women and youth groups have also played a pivotal role in the charge, and they stand firm in their commitment to realize democracy in Sudan. Women have long led resistance movements in the country. They have organized groups such as No to Women’s Oppression to protest the arrest of women who wore trousers, participated in sit-ins at military headquarters and constituted an estimated 70% of street protesters resisting the al-Bashir regime. Likewise, students have led protests across Sudan’s provinces and adopted slogans uniting Sudanese people across ethnic lines. Energized by the commitment of young and female activists, the resistance movement has been further bolstered by the success in toppling the al-Bashir regime.

The protesters, therefore, have learned from what works, but they have also learned from what doesn’t. Many protesters have anchored themselves in an anti-compromise stance, complicating international efforts to push for a solution. Compromising with the military previously led to the power-sharing government, whose defects ultimately led to the coup, so protesters are now hesitant to yield once more. For example, SPA turned down a UN initiative to begin negotiations between the military and the civilians. Other groups like the Forces of Freedom and Change (FFC) coalition, however, have encouraged the UN effort. Finding a solution therefore remains elusive, with democracy unlikely to be achieved in the short term and compromise for some seeming to connote only a temporary peace.

In a world plagued by mounting democratic decline, Sudan is an illustrative case of how everyday citizens can rise up against authoritarianism. However, the impacts of police brutality and removal of international aid provide solemn warnings that it is also the civilian population who will suffer the most, both at the hands of their own government and as a result of the international response ostensibly in opposition to that government. Targeted sanctions, such as those proposed during the United States Senate hearing on Sudan, could offer a more focused approach. However, it is unclear whether these would have the desired effect or merely worsen conditions for Sudanese citizens. Whatever the case, standing by as authoritarian leaders wrest power from democratic institutions is a perilous path for the international community.

It is apparent that the Sudanese military’s seizure of power and crackdown on protesters is not an isolated incident. Across the world, tenuous attempts at democracy are increasingly struggling to keep above water, and the war in Ukraine may further draw the line in the sand between those who align themselves with democracy and those who oppose it. In a possible sign that Russia seeks to cement its ties with fellow anti-democratic governments, the Deputy Chairman of Sudan’s Sovereignty Council, General Mohamed Hamdan Dagalo, known as Hemeti, visited Moscow on February 24, for talks soliciting Russian support. On the same day, Putin launched an invasion of Ukraine.

“Russia has the right to act in the interests of its citizens and protect its people under the constitution and the law,” Hemeti said.

This action contravened the urging of Western diplomats to condemn Russia’s aggression, although it may have contributed to tensions between Hemeti and Abdel Fattah al-Burhan, the head of the Sovereignty Council. Backing Russia may be part of an endeavor to stave off a hunger crisis, which was a significant factor in the fall of al-Bashir.

When it comes down to it, authoritarian governments isolated by Western democracies will seek support from one another. The position of countries like Sudan cannot be ignored, particularly in the face of popular movements for democracy. If Sudan is to realize its long-simmering hopes for democracy, international efforts should focus on diminishing the resources of the coup instigators and presenting a more stable solution than the previous attempt of joint military-civilian rule.

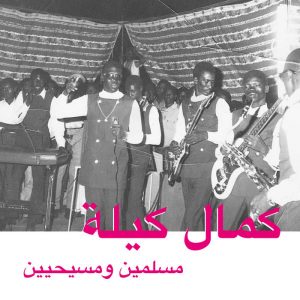

Featured Image Source: The New York Times

Comments are closed.