Welp. That was over quickly. Within an hour of the polls closing at 8 PM PT on September 14, the recall race was already called for Governor Newsom. Governor Gavin Newsom’s victory was basically the same as his 2018 landslide (both 61.9%).

The recall race has been estimated by Sonoma State University Professor David McCuan to have cost over $450 million, including $276 million in California taxpayer dollars, according to the California Department of Finance. It has also caused much anxiety and taken up media attention that undoubtedly deserved to be elsewhere. In short, it was a colossal waste of time and money, and a huge letdown for those fed up with Governor Newsom. The world has moved on, but I don’t think we should just yet. Let’s think about how we can improve this recall process to make it fairer for challengers, more democratic, and less of a money game.

Here’s how the recall works: The first question on the ballot asks if the governor should be recalled (removed) from office, and the second question asks which of the replacement candidates should replace the governor if the governor is recalled. The governor is not listed as one of the replacement candidates.

The first reason why the California gubernatorial recall process is unfair is that replacement candidates can’t receive donations from individuals, corporations, or PACs above $32,400, while the incumbent governor is not subject to those limitations. The incumbent governor can receive donations of unlimited dollar amounts. A case in point was when Netflix CEO Reed Hastings cut Newsom a $3 million check for the race. These one-sided rules contributed to the comically lopsided fundraising battle, with Newsom raising over $70 million (a low estimate), funded mostly by unions and corporations, and Newsom’s biggest challenger Larry Elder raising $13.9 million.

This one-sided affair was why, in the final stages of the campaign, my YouTube ads were flooded with anti-recall messages from Elizabeth Warren, Bernie Sanders, and Barack Obama. On Google and YouTube, Newsom spent almost $4.1 million, compared to Elder’s $600,000. They undoubtedly made a difference, as Democratic and Republican strategists would attest to; Kerman Maddox, a Democratic strategist in California and party fundraiser said, “If Gavin didn’t raise the money, given the amount of apathy and angst, he could have lost… I’m just going to be real.” And, GOP strategist and recall campaign veteran Dave Gilliard said of Newsom’s giant fundraising advantage: “It’s definitely made a difference.”

Another unfair element of California recalls is that political parties in California—namely the California Democratic Party and the California Republican Party—can give unlimited donations to candidates in state races, allowing them to put their financial weight behind candidates who serve party leaders over and instead of rank-in-file party members or members of the public. Money should never be a reason why a race is won or lost. People should win or lose on the basis of ideas. The governor should be subject to the same rules as challengers, and parties should be subject to limitations as well.

However, critics would argue that political parties should not be subject to contribution limits because they can be a moderating force in politics. Candidates need money to win elections and if political parties are restricted in their contributions, candidates will need to get their funds elsewhere. They would turn to large donors and PACs, which are very oriented toward special interests. Limiting the contributions of political parties, critics argue, could also give Super PACs more influence since their independent expenditures are not being balanced out—or neutralized—by political parties. While large donors, PACs, and Super PACs are special interests whose goals do not represent the public, political parties are large coalitions of the public. As such, critics would argue that political parties should have a good amount of influence on the candidate nomination process because they want candidates who can have broad appeal. On the other hand, special interest candidates are more polarized.

That being said, the fundraising process also unfairly penalizes less wealthy candidates. Currently, candidates can use as much of their own money as they want to fund their campaign, putting them at an unfair advantage over their less wealthy opponents. Candidates and the governor should not be allowed to self-fund as much as they want. Campaigns should be publicly funded with taxpayer dollars to give everyone an equal shot. Policymakers must decide how much money each candidate must be given and if each candidate must poll a certain number to get funds, so we don’t give out funds to unserious candidates.

Another way that the current system for recall elections benefits the wealthy is in the signature-gathering process. Campaigns have professional signature gatherers and if a recall campaign cannot afford them, it likely won’t be able to put a recall on the ballot. This isn’t a huge problem nowadays since both sides have boards of political cash, but it’s a flaw nonetheless. Establishing a nonpartisan state agency to poll Californians and conduct focus groups to see if there’s enough public support to warrant a recall would circumvent the signature gathering and verification processes, wasting less time and money.

Alternatively, California could use public money to fund signature gatherings. However, that would mean having to place restrictions on whose requests for recall signature funding would be worthy to avoid recall petitions popping up like weeds and taxpayer money being doled out to water them.

Also, California must reform and raise the threshold for the number of signatures needed for a recall. Requiring a number of signatures equal to 12% of the total votes cast in the last election is far too few. The recall must have enough public support to have a chance, so it isn’t just a huge waste of money like this one was.

Lastly and most importantly, we need to reform the recall process to make it democratic, period. Currently, if a majority of voters vote to recall the governor, the next governor will be the replacement candidate who wins the most votes. They don’t need a majority of the replacement vote (over 50%), just more than the other replacement candidates. In other words, they can still win even though they receive fewer votes than the incumbent governor.

Let’s imagine the following scenario: 51% vote to be called the governor, meaning 49% voted for them to stay in office. If 51% voted to recall the governor, they are out of office. The public is split on who should replace the governor if they are recalled. It’s a race between many candidates and the replacement candidate with the most support got 25% of the vote. All of the replacement candidates got less. The candidate who got 25% of the vote will be the next governor even though they received far fewer votes than the incoming governor (25% versus 49%). A scenario like this one was the fear of many going into the 2021 recall.

In fact, such a scenario has already played out in the past, not with a gubernatorial recall, but with a California State Senate recall, which uses the same process. In 2018, Senator Joshua Newman was recalled. 91,892 voted for his removal, and 66,197 voted for him to stay in office. The replacement candidate who got the most votes and won the seat got only 50,215 votes.

The person who is elected governor should win a majority of the vote. The simplest way to reform the process is to put every gubernatorial—including the incumbent governor—on the same ballot and ask voters to choose who they want as governor, with only one question. If one candidate wins over 50% of the vote, they’re automatically the next governor. But if no one reaches over 50%, the top two candidates with the most votes move on to a runoff between all of them, and the person who gets over 50% is the next governor. This is the process for non-recall California gubernatorial elections.

We need to stop referring to the process as a “recall election” and instead think of it more as a “snap election,” like in the UK Parliament. A snap election is when an election is called before it was originally scheduled to occur, but it works the same as any other election. The question on the ballot will no longer be about if the governor should be “recalled,” but rather who should be governor. This will produce more democratic outcomes and has the added bonus of scourging the word “recall” from this entire election. The word “recall” is confusing because unfamiliar voters have no idea what it means. When you search “recall” on Google, the recall process is in the third definition. The first definition is “to remember” and the second is “to order something back,” like a manufacturer recalling a dangerous product. The word “recall” confuses voters, so let’s get rid of it altogether.

Critics of changing the recall election procedure would argue that the recall election should remain a unique procedure centered around the removal of an elected official, not just like any other election. Other critics would argue that the recall process balances out the power in California between Democrats and Republicans since it’s the only feasible way a Republican can be elected governor. They would argue that Republicans in California deserve to have representation in the governor’s office too.

Taken altogether, these reforms would redistribute power from donors to voters. While the 2021 recall election was a grand waste of time and money and accomplished little, it does give us the opportunity to analyze the procedure and propose reforms. Hopefully, this will start a nationwide trend of state by state and federal reforms that would make our political system more accountable to people, not money, and actually reflect the will of the voters.

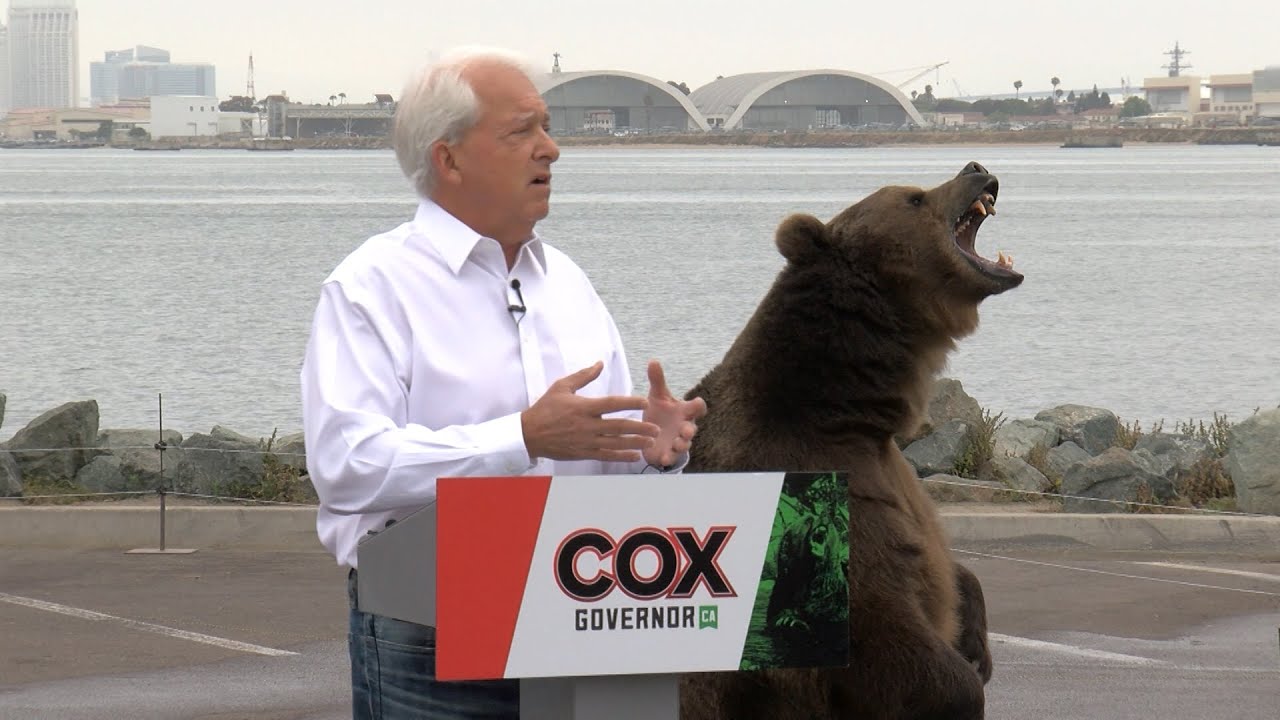

Featured Image Source: KPBS, John Carroll

Comments are closed.