On a cold day in January of 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a Black woman from Virginia, rushed to the Johns Hopkins Medical center after experiencing heavy vaginal bleeding and severe uterine pain. Dr. George Otto Gey, a white, male physician, examined her, diagnosed her with a severe case of cervical cancer and began treatment. Eight months later, Lacks died in the “colored” ward of the hospital, her body disposed of in an unmarked grave. Unbeknownst to her or her family, Dr. Gey took samples of the cancerous cells from Lacks’s cervix during an examination. These cells not only outlived Henrietta; they revolutionized modern medicine.

The HeLa Cells

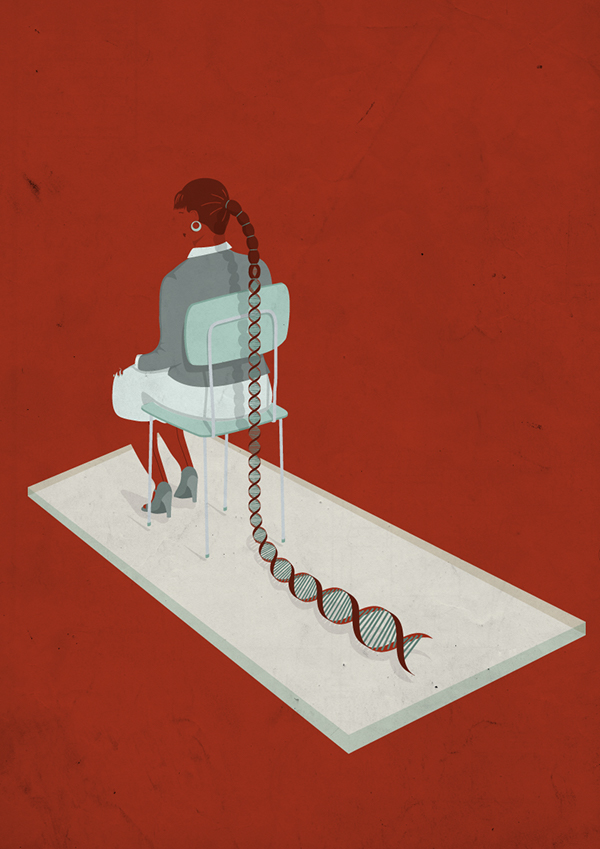

The cancerous cells Dr. Gey took without Henrietta’s consent had a strange quality to them: they never died. Named the HeLa cells after Lacks’s first and last name, these cells continuously multiplied and were thus deemed “immortal.” The scientific community shared the cell line amongst themselves and used it for various types of research. From developing vaccinations and drugs to helping humans walk on the moon, the HeLa cells were used in countless clinical trials, even helping create the Covid vaccine. Henrietta’s cells have quite literally shaped medicine as we now know it.

While Dr. Gey himself gained no profit from the HeLa cells, by distributing them amongst his colleagues, he inadvertently allowed for their commercialization. They have since generated billions of dollars for various scientific companies, helped people win Nobel Peace Prizes, sent man to space, and accomplished much more, with few people knowing their origin.

And what did the Lacks family get? Nothing.

It wasn’t until over 20 years after Henrietta’s death that her family even knew the cell line existed—and they only found out by accident. Researchers continued to exploit the Lacks family and their lack of medical or scientific experience as poor, uneducated Black Americans. When the Lacks family heard that scientists were working with Henrietta’s cells, they believed these very scientists were experimenting on her corpse in horrific ways.

Even worse, countless pharmaceutical companies and individual scientists have patented different methods of using the HeLa lines, with companies like Thermo Fisher Scientific making billions from the genetic material. With these companies selling Henrietta’s cells at $25 per vial, the profit generated by her genes is phenomenal. And yet, her family has continued to struggle to survive, with one of Henrietta’s sons living homeless for a period of time and many of them lacking health insurance and unable to get treatment for their illnesses. Her daughter, Deborah, explained her frustrations:

I always have thought it was strange, if our mother cells done so much for medicine, how come her family can’t afford to see no doctors? Don’t make no sense. People got rich off my mother without us even knowin about them takin her cells, now we don’t get a dime. I used to get so mad about that to where it made me sick and I had to take pills. But I don’t got it in me no more to fight. I just want to know who my mother was.

Who Was Henrietta?: The Woman Behind the Cells

Henrietta Lacks deserves to be known for more than just her cancer cells.

Born on August 1, 1920 in Roanoke, Virginia, Lacks lived 31 years filled with joy, laughter, and dancing around the kitchen table with her children. She had a challenging childhood—after her mother died when she was only four years old, her family moved to Clover, Virginia and her father left. She and her nine siblings were split up among family members, and authorities gave Henrietta to her grandfather, Tommy Lacks.

Henrietta had very little education, finishing school after sixth grade and working on her grandfather’s farm as a child instead. She was “the prettiest girl in Lacks Town” and was known for her darling smile and warm eyes. Two of her cousins, David (“Day”) and “Crazy Joe,” constantly fought for her attention, despite the fact that her and Day shared a room in their grandfather’s house. Her and Day had their first child together when she was fourteen. Soon after, they had a daughter, Elsie. Elsie had a form of epilepsy or neurosyphilis, but at the time her family only described her as “simple.” After Henrietta had more kids, she was unable to spend the time and care on Elsie that she needed. The child she once dressed in homemade dresses and lovingly rocked back and forth at night began bumping into walls and doors, burning herself accidentally on the stove, or running out into the streets in a seeming delirium. So, Henrietta and Day sent Elsie to the Hospital for the Negro Insane, and “a bit of Henrietta died [that] day.” The dedicated mother visited her daughter once a week from there on out.

As a mother, wife, sister, and beloved friend, Henrietta’s life revolved around those she loved. Her cousins loved her spaghetti dinners; family members deemed her rice pudding “famous.” Henrietta and her cousin, Sadie, frequently went out dancing when Day worked the night shift, Sadie saying that “Hennie made life come alive—bein with her was like bein with fun … Hennie just love peoples. She was a person that could really make the good things come out of you.”

When doctors took Henrietta’s cells, it was common practice for doctors to use patients from public wards for research without their knowledge. At Johns Hopkins, Dr. Gey had been using patients’ cells to attempt to find the cause and cure of cancer; he described himself as “the world’s most famous vulture, feeding on human specimens almost constantly.” It wasn’t until Lacks’s cells that his vulturous hunger was satiated.

The scientists working with HeLa cells did everything they could to force Henrietta Lacks into anonymity, claiming the cells derived from a woman named “Helen Lane” rather than admitting to their unethical past. Not only was this deception a disservice to the woman killed by these very cancer cells, but it also prevented her family from gaining any financial or emotional compensation for the loss of their beloved mother, wife, and friend.

While Henrietta’s life only lasted 31 years, her legacy lives on in her immortalized cells and their gifts to the world of science and medicine. We owe so much to Henrietta, and her family deserves compensation for her contributions and for the wrongful way they were made.

The Tuskegee Syphilis Study

The injustice of Henrietta Lacks’s story has opened the medical community to a new standard of care, bringing to light “several bioethical issues, including informed consent, medical records privacy, and communication with tissue donors and research participants,” according to Johns Hopkins. The use of cells in research is complicated and convoluted, and the question of ethics related to cell ownership plagues the scientific community.

There is a deep rooted history of Black inequality and abuse in science. In the 1930s, governmental researchers at the Tuskegee Institute began a study on syphilis, entitled the “Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negros Male.” Over 600 Black men participated in the study, with none of them providing their informed consent. During the study, penicillin became widely available as a treatment for syphilis, but none of the study participants were offered the treatment. The experiment only ended in the 1970s after the Associated Press reported that “the federal government… had let hundreds of black men in rural Alabama go untreated for syphilis for 40 years for research purposes” and public outrage ensued. There’s no doubt why countless Black Americans refuse to participate in clinical trials (only 3.1% of clinical trial participants for cancer drugs are Black, for example, yet cancer is the second highest cause of death for Black men and women within the United States). The scientific community has failed Black Americans by refraining to provide safe and trustworthy medical services that do not treat Black bodies as disposable. In order to gain proportional representation in medical studies, doctors must first reevaluate the way they treat Black patients.

Our country has historically failed the Black community, and we still have a ways to come. After the implementation of the Affordable Care Act, the uninsured rate among Black people declined and allowed for many Americans to gain healthcare accessibility. Still, around 15% of Black Americans are uninsured. This number is even worse for Hispanic Americans, with a 2% increase of uninsured from 29.3% to 31.4% in the past year. Henrietta is but one of many non-white Americans who experience healthcare inequality.

Changes in Scientific Legislation

After the Tuskegee Syphilis Study, the government adopted the National Research Act and created a commission to protect human subjects involved in clinical research. Researchers were now required to get voluntary informed consent from participants in their clinical studies. A few years later, the commission published the Belmont Report identifying “basic ethical principles and guidelines” for human clinical trials. The government was determined to make sure nothing like the Tuskegee Syphilis tragedy occurred under their dime again.

In 1991, the Common Rule was adopted, acting as standardized guidelines for federally funded research on human subjects, seeking “to present a unified ethical and regulatory framework for the future.” The Common Rule originally lacked certain important specifications that would protect the human subjects. While informed consent forms were provided, the medical jargon and dense information made it difficult for ordinary citizens to fully understand what they were signing up for.

In 2017, however, the Common Rule was revised, requiring that informed consent forms present key information about the study easily legible at the top of the document; the informed consent process is documented digitally; consent forms are publicly available; among other administrative changes to lighten the administrative burden for researchers.

Yet, the Common Rule has limitations. Since it only applies to federally funded research, anything outside of the federal domain remains unregulated and complicated, especially in regards to technological usage of human data. Moreover, not all human subjects research has to be approved by the Institutional Review Board (an ethics committee). Even worse, unidentified biospecimens (blood, tissue, anything “not associated with private information that could be used to identify the donors”) remain uncovered by the law. Even NIH director Francis Collins argues that the Common Rules needs revisions that protects the privacy of human subjects through informed consent on the usage of biospecimens, “regardless of identifiability.” He writes:

. . . the US biomedical research community should do more than simply acknowledge that what happened to Lacks and her family was regrettable. It is time to take concrete action by establishing a Henrietta Lacks biospecimen consent policy, and thereby ensure that what happened to this woman and her family will never happen again.

The Legal Battle Against a “Racially Unjust Medical System”

In a groundbreaking lawsuit, the Lacks family estate sued Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., a biotechnology company using HeLa cells without any consent from the family. Directly fighting against the commercialization of stolen cells, the lawsuit challenges the lack of firm verbiage against use of unidentified biospecimens in the Common Rule. The lawsuit asks Thermo Fisher Scientific to disgorge any profits obtained from the HeLa cell line to the Lacks Family Estate and to refrain from using HeLa cells without the Estate’s formal permission.

Ben Crump, one of the Lacks family lawyers, stated: “It is outrageous that this company would think that they have intellectual rights property to [the Lacks’s] grandmother’s cells. Why is it that they have intellectual rights to her cells and can benefit billions of dollars when her family, her flesh and blood, her Black children, get nothing?” Another lawyer later hinted that this lawsuit was only the beginning; the Lacks family intends to sue more biotech companies using Henrietta’s cells for commercial profit. The United States Justice system must finally fight for Lacks and hold these companies accountable.

Henrietta’s Lasting Legacy: What Now?

On October 13th, 2021, Henrietta Lacks received global acknowledgement for her postmortem impacts on the scientific world. The World Health Organization presented the Lacks family with a posthumous award to Henrietta, finally acknowledging her lasting contributions to the medical field. The presentation of the award featured world renowned scientists, doctors, along with Henrietta’s family members, reminding the world of the importance of the HeLa cells and the woman behind them.

After the 100th anniversary of Henrietta’s birth, doctors in the World Health Organization launched a campaign to eliminate cervical cancer with the approval and advocacy of the Lacks Family. The family also tirelessly advocates for global access to the HPV vaccine, a “life-saving tool that protects against cervical cancer but remains inaccessible to girls in some of the poorest and most heavily burdened countries.” Beyond the HeLa cells themselves, Henrietta Lacks’s legacy remains alive and thriving thanks to the modern efforts of her descendants and doctors worldwide.

Henrietta Lacks deserves more than recognition. Learning about her life and legacy in high schools needs to be commonplace; history books should tell her story and the role she and her family played in combating racism in the medical industry. Her story is a common one for Black people throughout history, and an important step towards righting the historical wrongdoings is through education and reparations. Schools cannot stop at just discussing the HeLa cell lines. They must teach of Henrietta Lacks herself.

Featured Image Source: Madan Law PLLC

Comments are closed.