In August, Democratic candidate Mary Peltola was projected as the winner of a special election in Alaska to fill the state’s lone congressional district following the death of former Republican congressman Don Young. Peltola beat the odds to win the seat, with pollster FiveThirtyEight forecasting just a 14 percent chance of victory in a state that Donald Trump won by 10 points in 2020. A key part of Peltola’s upset win against Republican challengers—including the divisive former governor Sarah Palin—was Alaska voters’ narrow approval of ranked-choice voting by ballot initiative in 2020.

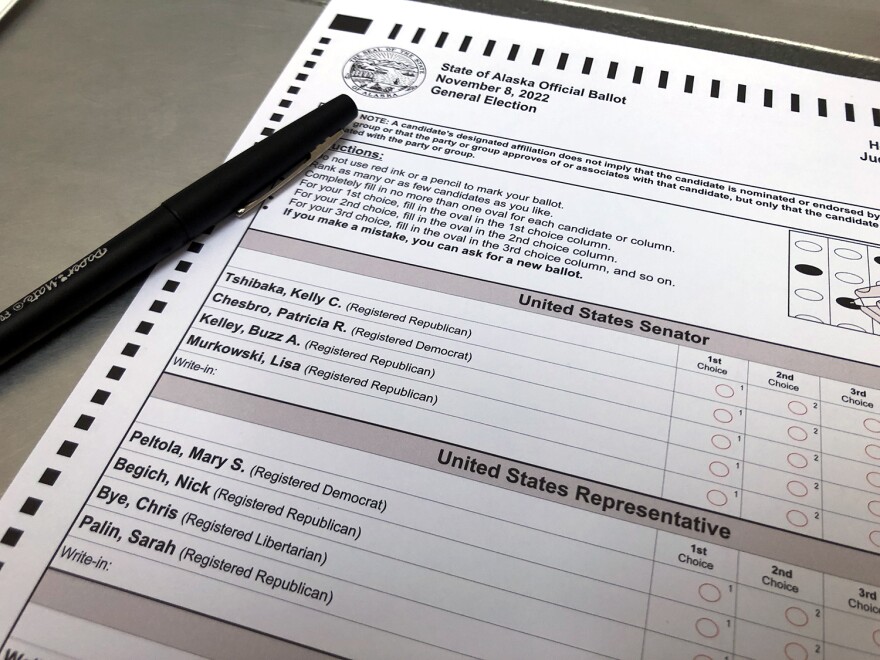

Ranked-choice voting (RCV) is a system of balloting that many Americans aren’t familiar with. RCV requires that voters give numeric ranks to candidates in the order of their preference; to win, a candidate must attain at least a 50% majority. If no candidate achieves this threshold after votes are initially tabulated, candidates at the bottom will be eliminated and their votes redistributed in the order of voters’ preferences in as many rounds necessary for a candidate to achieve this threshold. In contrast to RCV, most Americans are instead familiar with the concept of first-past-the-post (FPTP) method of election, whereby a candidate only needs to secure the most votes out of all other candidates contesting the election. This means that a candidate could win with a hypothetical 25% of votes as long as no other candidate surpassed this vote count. In essence, RCV is majoritarian while FPTP is pluralitarian.

In Alaska’s special election, Peltola was the only Democrat in the runoff from the primary. She was joined by Republicans Nick Begich III and Sarah Palin. Another candidate, independent Al Gross, dropped out after finishing fourth (though qualifying for the runoff) in the primary. While Peltola consolidated support as the only Democrat, the scars held by Begich’s and Palin’s supporters from the primary remained unhealed well into the runoff: a little less than 29 percent of Begich’s voters ranked Peltola before Palin on their ballots. A significant number of Begich’s voters also did not indicate a second choice, leaving the rest of their ballots blank. Crucially, only a little more than half of Begich’s voters ranked Palin as their second choice. The transferred votes from Begich coupled with the refusal of other Begich voters to vote for Palin were enough to propel Peltola to victory with a 5,000 vote margin over Palin. As Scott Kendall, a proponent of the Alaska voting system, said in the New York Times, “the campaign that Nick Begich ran was a clinic in how to have your party lose a ranked-choice election.”

While ranked-choice voting ensured that Peltola had support in one way or another from at least half of Alaska’s voters, the system does not always work perfectly. A cautionary tale can be found in the 2021 New York City mayoral election primaries which were hotly contested on the Democratic side. In this election, the city’s Board of Elections mistakenly counted 135,000 test ballots and released the results before retracting them. This experience sowed mistrust in the voting system and the results, leading to criticism from all candidates.

Source: Economic Times

RCV gives voters more choice in the process to choose candidates they really want to see in office while also reducing political polarization. In a plurality voting system like FPTP, voters may vote strategically for a candidate that may not have been their first choice but has the best chance of winning in the interest of ensuring that their least preferred candidate loses. Under ranked-choice voting, individuals can vote for their most preferred candidate knowing that if their candidate doesn’t win, their vote won’t be wasted. The requirement that candidates achieve a majority of votes to win ensures that candidates must have broad political appeal, as happened in Maine in 2018. This means that candidates would have to form coalitions with other candidates and reduce the level of fiery political rhetoric that has come to define American politics in the interest of not alienating voters that they would need if ranked-choice voting were to be triggered. For example, Democrats Jane Kim and Mark Leno cross-endorsed each other and urged voters to rank them both in San Francisco’s 2018 mayoral election. In Peltola’s case, she didn’t necessarily have broad political appeal as much as benefiting from being the ‘odd’ one out of two Republican candidates who waged a negative campaign that split the conservative vote. Peltola’s lack of political dis-appeal, something that Palin didn’t have with Begich voters, pushed her over the top.

Opponents of ranked-choice voting could argue that the system is confusing and enables questions about validity of results. Gabrielle M. Etzel argues for the Foundation for Government Accountability that expecting voters to know all relevant details about all the candidates on their ballot is unrealistic. Princeton professor Nolan McCarty agrees, saying “ranking candidates is confusing for voters – and that confusion only increases as more candidates are added to the ballot.”

Critics also argue that RCV leads to depressed turnout in elections. Etzel uses Minneapolis and St. Paul—two Minnesota cities that use the method—as examples since they “lag well behind other major metropolitan cities in municipal election voter turnout.” San Francisco, over a period stretching from 1995 and 2011, revealed a strong relationship between lowered voter turnout and implementation of RCV.

There are also arguments that RCV is not truly majoritarian. As mentioned previously, voters can rank up to the number of candidates on their ballot. However, voters who don’t do that exhaust their ballots. Thus, when none of their preferred candidates win, they lose their voice in choosing their representatives: “their ballot doesn’t figure in the outcome.” In San Francisco’s 2011 mayoral election, 27% of ballots were exhausted after the first round, meaning that over 25%of voters did not have a say in who was elected mayor.

Source: Alaska Public Media

Critics further point out that RCV is “a scheme to keep politicians in power.” One of the leading proponents of the 2020 RCV ballot measure was Scott Kendall, who had run Senator Lisa Murkowski’s past campaigns. Murkowski lost the Republican nomination for U.S. Senate in 2010 and subsequently ran and won a write-in campaign. She stands to benefit from the implementation of RCV as she is running for re-election this year after opposition to some of former President Donald Trump’s actions during his term, including voting to convict him on impeachment charges following the January 6 insurrection. Murkowski was subsequently censured by the Alaska GOP and faces a strong challenger in fellow Republican, Trump-endorsed Kelly Tshibaka. But, as Kendall says, “candidates can make their case to the entire constituency, rather than only the party faithful.” Murkowski will benefit from RCV in Alaska by potentially being able to power her re-election with votes from Democrats, independents, and third-party voters as well as sympathetic Republicans.

Despite the criticisms, RCV is not a uniquely American phenomenon. Australia, Ireland, and New Zealand all use the balloting system for their elections, just to name a few. In Australia, a form of RCV has dominated the country’s elections for over a century. The country combats exhausted ballots through compulsory ranking of preferences for every candidate. It is also a case study for how RCV prevents political extremism: “lower house electoral politics a contest for the middle ground.”

On the other hand, Canada and the United Kingdom both share the distinction with the United States of utilizing FPTP to elect their politicians. Canada suffers from a similar problem to the United States where many officials are elected with pluralities: members of Parliament from 205 of 338 ridings (national electoral districts) did not win a majority victory in the 2015 federal election. In the United Kingdom, a similar problem exists, leading to questions over if FPTP is truly democratic. However, unlike Canada and the United States, British voters were asked to decide their country’s electoral system in 2011 through a referendum for an alternative though it ultimately failed.

Circling back to Australia, the Oceanian country demonstrates the feasibility and practicality of deploying RCV on a national scale while also addressing some of the opposition to the method: compulsory ranking of candidates counters non-majoritarian criticism, political extremism is reduced, and turnout rates are high (Australia has compulsory voting). Though Australia has a comparatively smaller population, its close relationship, culturally and politically, with the United States means it is an excellent case study for applying RCV.

America has always valued its leadership from the American experiment, and RCV is no different. Many parts of the United States have already successfully implemented the system and, although it isn’t a catch-all to fight the woes of American democracy, ranked-choice voting offers a beacon into expanding voter choice. Ranked-choice voting has a learning curve as voters develop habits in ranking their candidates and elections officials around the country implement it. But it is this spirit of experimentation that has created the current, unique brand of American democracy we have today—RCV is simply another locus of democratic development.

Featured Image: Alaska Public Media

Comments are closed.