The weather has been a running joke for residents of San Francisco. Karl, the name they have given their fog, blankets their sky year-round. There is no snow season (it has snowed six times in the last 150 years.) And, due to California’s historic drought, residents of The City are losing their rainy season. But over the last decade, one season has crept into existence: fire.

A State at War with Residents, Weather, & Water

Record-breaking fires are no longer an oddity to residents of California. Year after year, California’s wildfires are causing more destruction, more damage, and more death. “What’s changed recently since things started to get quite bad is it really seems like just some significantly dry years,” says Andrew Johnson, a Ph.D. candidate working in UC Berkeley’s Stephens Lab, which focuses on research and education in wildland fire science.

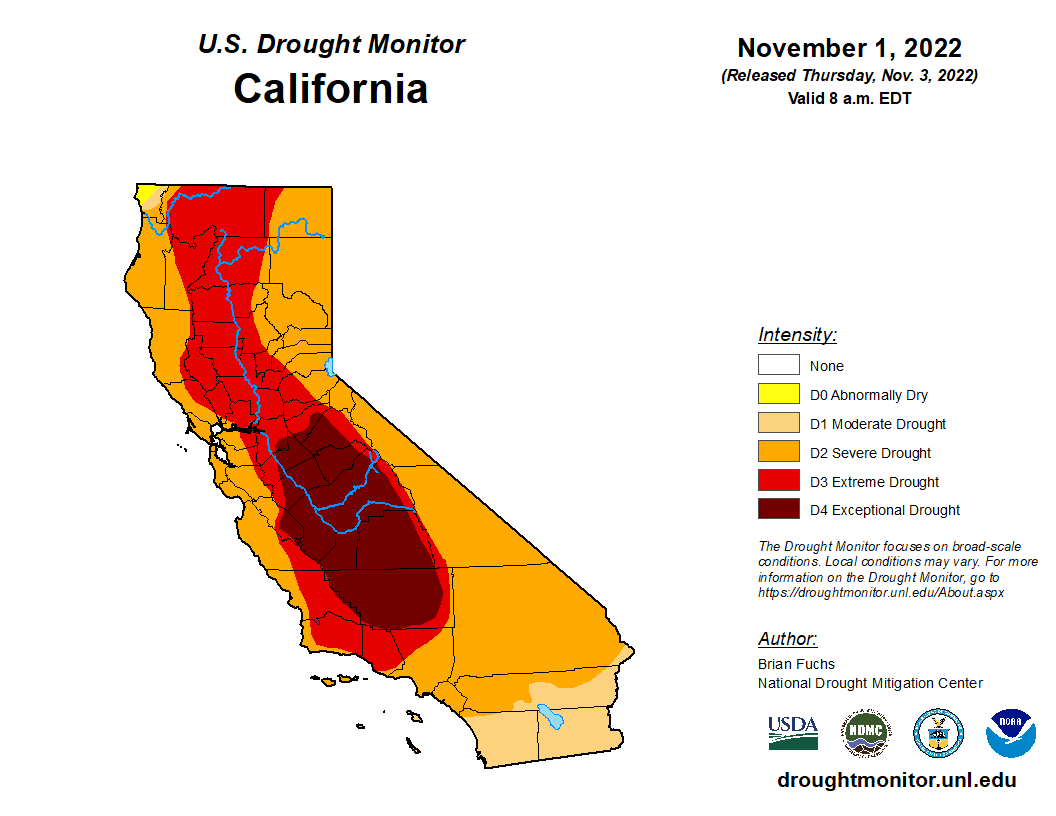

Along with rising sea levels, forest fires are on the front lines of an impending climate crisis. Throughout the last decade, California has been teetering back and forth from “Severe Drought” to “Exceptional Drought.” This historic drought has removed water from the state’s ecosystem and left California dead and dry.

The growth in California’s population also appears to play a role. As California real estate becomes increasingly unattainable, many Californians have been forced to move further away from costly cities. Trinity County, located in Northern California, is the state’s most rapidly growing county, increasing in population by over 20 percent since 2010. The county is relatively rural, given that Weaverville, the largest consolidation of people in the county, has a population of 3,667. As the population has grown, Trinity County has parallelly become one of the counties most impacted by recent massive wildfires. Between 2017 and 2021, four of the state’s largest wildfires have impacted the county.

“The expansion into what we call the ‘wildland-urban interface’—expansion into rural areas—is definitely a big contributor to fires,” says Johnson. “[You] have more potential sources of ignition if people accidentally start [a] fire.”

“I wouldn’t say it is the biggest part of the problem by any means,” Johnson continues. “I would just say it’s a fair amount of the problem.”

“How did we get to this point?” Johnson asks rhetorically. “It really is mostly forest management.”

Failed Forest Management

Fires have shaped California throughout its history. But more recently, politics and public perceptions have turned the state away from a phenomenon as old as the state itself.

“Burning as a management tool goes back thousands and thousands of years. Native Americans used fire…to do things like make pathways or to reduce the risk of fire,” says Johnson.

Indigenous Peoples employed land-burning practices to maintain the health of their land. “This is old land,” says Robert Goode, tribal chairman of the North Fork Mono Tribe. “It’s been in use for thousands and thousands of years. And so what we’re doing out here is restoring life.”

But that is a lesson that modern American forest managers have long since forgotten. In 1910, Americans got their first taste of massively deadly fires. ‘The Big Burn’ or the Great Fire of 1910 demonstrated to Americans the true danger of wildfires out of control. The Great Fire of 1910 burned three million acres in Northern Idaho and Western Montana, killing 87 people, the majority of them firefighters. It burned down many towns and resulted in a billion dollars of damages.

In the aftermath of the fire, politicians raced to ‘improve’ America’s fire response capabilities. In reality, politicians’ response to the fear of fire was too aggressive.

One such policy was the ‘10 AM rule,’ put in place by the Forest Service in 1935. The policy demanded that “every fire should be suppressed by 10 a.m. the day following its initial report.” Aggressive policies like this caused minor fires to be suppressed immediately, rather than burn their course.

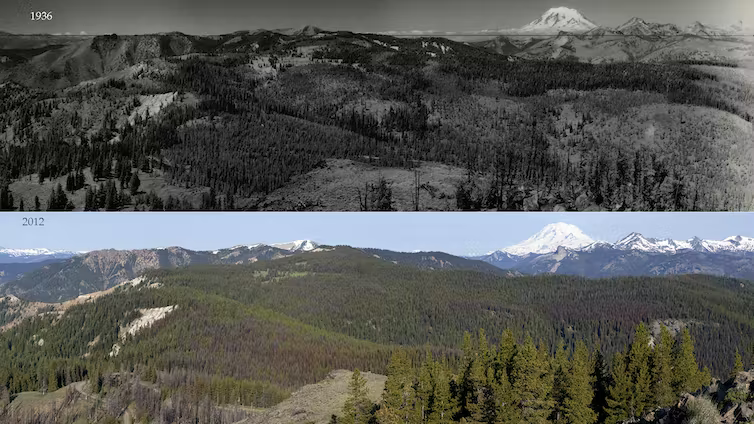

American fear of fire in the aftermath of the Great Fire of 1910 ushered in an era of overly suppressive forest management techniques. This left large portions of the country, especially California, overgrown and highly flammable.

“They instituted a policy of what we call fire exclusion. They excluded fire from the landscape and then started putting out all fires. And that has been done, they’ve been doing that since like the early 20th century. So now you have over a century of fuel, of what we call fuel,” says Johnson. Over-suppression of wildfires caused forests to become too unburned and too dense.

Current Solutions & Where We Go From Here

California forests have long been mismanaged. But there is an active movement on the West Coast to look to the past for help moving forward.

“[A] prescribed burn is an intentionally set fire under various specific sets of conditions,” Johnson tells me. “[They]could be just to reduce the risk of a catastrophic or a bad fire in the future by reducing the amount of flammable vegetation rotation.” Prescribed burns create the perfect conditions for plants that need fire to grow, such as certain pine trees. They also facilitate the growth of species that thrive in a burned environment.

Prescribed burns are California’s best step forward. But due to red tape, prescribed burns are easier said than done. Government agencies, such as the California Air Resources Board (CARB), provide the biggest limitation to prescribed burns. CARB sets air pollution limits that stand in the way of intentional fires. “[P]rescribed fires do produce a certain amount of smoke. Smoke is a big limiting factor,” says Johnson. “There’s so much of it that it’s very challenging to accomplish a prescribed burn.”

Some organizations have persisted even still. The Colville Tribes in Washington State, for instance, are on the frontier of using prescribed burns to manage their land.

“Without management, we’re trying to convert these types of areas that were…unmanaged”, says Cody Desautel, natural resource director of the Colville tribes. “We get to manage what species composition is, what the stocking is, so when we see these types of fire events in the future, you don’t see this type of severity, where you have a hundred percent mortality.”

While there are many ecological benefits to a well-maintained forest, direct profit is also one. The Coville Tribes generate 8-10 million dollars annually through logging. “That supports the tribal budget, and that supports both natural resource goals and objectives, but also non-natural resource objectives, such as healthcare, education, law enforcement,” Desautel explains.

Through forest mismanagement, California has brought itself to the state that we are today. Foresters up and down the West Coast are seeing the harms of aggressive fire suppression and shifting back to Indigenous People’s original forest management techniques. Desautel says that the tribes’ goal is “replicating [the] historic conditions that would have been here pre-European contact.” And, if California wishes to undo the harm done to the state’s forests, it should make that its goal as well.

Featured Image: SFGATE

Comments are closed.