Like a gathering flood, the United Farm Workers-led caravan of protestors surged toward the state capitol. Along the capitol mall, a throng of supporters gathered in a state of animated anticipation.

The approaching human mass was a cacophony of sensory stimulation.

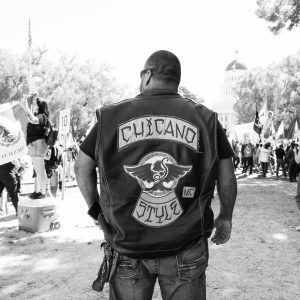

The Chicano Styles motorcycle club acted as a vanguard for the marchers on foot, thundering towards the capitol building on a pack of candy-painted choppers glistening in the bright midday sun. Behind them, a river flowed forth. The protestors were weary but spirited. Many wore work clothes: sun-faded jeans and thick high-top boots, wide-brimmed hats, and red UFW t-shirts.

Among the marchers, traditional dancers pirouetted and stomped their feet to the rhythm of drums pushed tirelessly along on wheeled carts. Some burned bundles of incense, filling the air with wisps of aromatic smoke. As the caravan descended on the capitol building, a chorus of conch shells filled the air.

The dancers’ brightly colored penachos, or pheasant-feather headdresses, swayed and undulated in time with the beat. Their ankles bore ornately-adorned cuffs of cowry beads; with each rhythmic footfall, the figurative heartbeat of the movement pulsated through the crowd.

The march began twenty-four days earlier and a winding 335 miles to the south at the Forty Acres, the historic headquarters of the United Farm Workers nestled in the valley fields west of Delano. It was at the Forty Acres where, in 1968, Cesar Chavez carried out a twenty-five day hunger strike to protest better working conditions and wages for farm workers.

More than a half-century later, many of the issues that the then-nascent UFW sought to address remain at the forefront of California’s agricultural politics. The caravan of protestors that arrived at the capitol building marched in support of State Assembly Bill 2183, a bill that would legislate a suite of rights and protections for workers voting in union elections. For thirty days, a determined group of protestors remained at the capitol building, calling on Governor Gavin Newsom to sign the bill into law.

The governor had previously held out on signing the bill, despite pressure from President Biden. Part of the problem was that the bill would have allowed workers to vote by mail in union elections. “We cannot support an untested mail-in election process that lacks critical provisions to protect the integrity of the election,” explained the governor’s communication director Erin Mellon. But on September 28th, the thirty-first day of the protestors’ vigil, the governor relented. “CA’s farmworkers are the lifeblood of our state & have a fundamental right to unionize and advocate for themselves in the workplace.” Newsom’s office said in a statement announcing the bill’s passage.

The bill became law with the promise that legislators would make changes to it during the next legislative section. In its current form, the law allows workers to vote by mail. However, the bill was signed with the promise that this provision would be removed in the next legislative session. A key edit involves the removal of the proposal to allow farmers to vote by mail. Nonetheless, the law preserves the ability of workers to form a union via “card check”.

Under the traditional framework, union organizers are required to prove workers’ interest in a union election before they can make the case that an election should occur. Union advocates claim that having to pass through multiple hoops before a union election can take place leaves organizers vulnerable to coercion and intimidation.

The card check process – so named because of the cards that organizers sometimes use to gather signatures – allows organizers to circumvent the traditional route to unionization. In order for workers to unionize, the card check process simply requires proof of majority support for a union among workers. Under the new legislation, prospective union members are allowed to vote by dropping off ballot cards at designated locations or by signing a petition. Additionally, because they no longer have to prove workers’ interest in an election, union organizers are not obligated to disclose their intent to unionize. Once organizers gather enough support, California’s Agricultural Labor Relations Board has the option to certify the union.

Despite the jubilant scene on the capitol mall after Newsom’s surprise change of heart, the bill did not receive universal support. The California Farm Bureau, a group representing farmers and ranchers and one of AB2183’s most vocal opponents, expressed disappointment at the bill’s passage. The bill’s critics allege that the card check process reduces oversight in the unionization process and may allow unions to intimidate workers into supporting their cause. Some have also expressed concern that the bill may increase the instance of fraud if union members are allowed to unfairly prefill workers’ cards under the pretext of translation.

AB2183’s passage will allow farmworkers the opportunity to seek representation and bargaining power. The Public Policy Institute of California estimates that over 90 percent of California’s farmworkers are immigrants, and more than half of them are undocumented. The threat of deportation often looms over the heads of undocumented farmworkers seeking to advocate for better working conditions.

Prior to AB2183, prospective union members were only able to vote in person at polling sites designated by the Agricultural Labor Relations Board. These polling locations were typically located on the employers’ property, creating a climate ripe for voter intimidation.

The bill’s passage was brimming with symbolism. The once-mighty UFW had been struggling, with estimated membership as low as 7,000. UFW supporters say that this is due in part to the challenges of organizing a labor force composed of workers uniquely vulnerable to coercion. With the success of AB2183, the UFW has reaffirmed that it is still a force to be reckoned with in the state capitol. And while the impact of the new law remains to be seen, the protections enshrined will undoubtedly make it easier for farmworkers to unionize if they choose to do so.

Moreover, the recent legislative changes came as climate change has made working conditions ever more dangerous for laborers. As protestors marched to the capitol, temperatures routinely soared into triple digits. Such temperatures have become the norm during the growing season in the arid Central Valley, where farmworkers are doubly vulnerable because of the physical nature of their work and the lack of shade in the fields.

In 2015, UFW efforts resulted in mandatory changes to workplace practices after a pregnant woman fainted and died while working in triple-digit temperatures. The changes included the implementation of guidance improving access to shade, as well as the requirement that water be provided to employees free of charge. Workers were also more easily able to report violations, and employers were ordered to implement heat illness prevention plans.

Ultimately, AB2183 helps eliminate the barriers preventing farmworkers from raising their voices against the powerful agricultural conglomerates that dominate Central Valley politics. Farmworkers – not the wealthy landowners for whom they work – remain the bedrock upon which rests California’s status as an agricultural powerhouse. Yet they are continually mistreated and underrepresented, both in the workplace and in the state capitol. AB2183’s passage marks a small step towards justice.

Amidst the jubilant crowd of dancers and protestors waving red UFW flags celebrating the law at the foot of the capitol building, one could not help but feel a prevailing sense of hope.

Featured Image Source: Jonathan Hale

Comments are closed.