“The school boards are the key that picks the lock,” said former Trump advisor Steve Bannon in August of last year. Bannon, along with other vocal conservatives, has been avidly pushing for takeovers of local political institutions such as school boards—and they’re winning.

The recall failure trend ended on February 15th, 2022, when San Francisco voters ousted three members from the Board of Education, a keystone progressive city institution. In a city more Democratic than its heavily Democratic state, the response from voters to the school board recall was met with shock.

“I definitely know [the political landscape] has changed,” recalled President of the Board of Education, Gabriela Lopez, told me over the phone one rainy morning in early January. “When I was elected in 2018, even the field of candidates was completely different.”

“Starting with the governor,” Lopez continues, “[people learned that] infinite resources and infinite funding can get something on a ballot.” Lopez claims that recall proponents hired individuals from out of state to gather signatures, an expensive process that would not be possible without large amounts of funding. While acknowledging that frustrations with the closure of schools during the pandemic were a factor, Lopez believes that other motivations led the recall charge. “There were multiple people who wanted elected [officials] removed … who were focusing on inequities, racial injustice, a lot of things that people in power, people with privilege don’t really want us to talk about.”

In that way, Lopez finishes, the recall of the school board and the District Attorney four months later were “hand in hand.”

Four months after the recall of Lopez and her Board-member colleagues, Fauuga Molina, and Alison Collins, another recall took place in San Francisco. This time, the recall was of District Attorney Chesa Boudin, a promoter of restorative justice initiatives and mass incarceration reduction. Boudin, just like other progressive D.A.s across the country, had been in the spotlight since day one. His opposition was diverse, from the head of the San Francisco Police Union to national media figures like Tucker Carlson.

But shifting political landscapes is the symptom, not the cause of successful San Francisco recalls. Lopez believes that her opposition in her recall was not disgruntled parents, yet rather a greater political force. “Ultimately, I know that this was a tactic that was used by outside forces … across the country.”

Election records back up that statement. SF Guardians, a 501(c)(4) social welfare organization that behaves virtually as a campaign donation vehicle, spent a total of $20,683.97 opposing Lopez in 2022. From that, thousands of dollars came were donated from around the country, from New Hampshire to Washington D.C.—the largest being a $7,000 donation from Kilroy Realty, a real estate investment trust firm based in Los Angeles.

The trend of out-of-state donations doesn’t stop there. Speaking on the Boudin recall, Richie Greenberg, a local conservative political critic and director of Recall Chesa Boudin, the campaign calling for the recall of the District Attorney, stated proudly that the movement to repudiate San Francisco’s District Attorney was not just local, but national. “International, too!” Greenberg said, grinning.

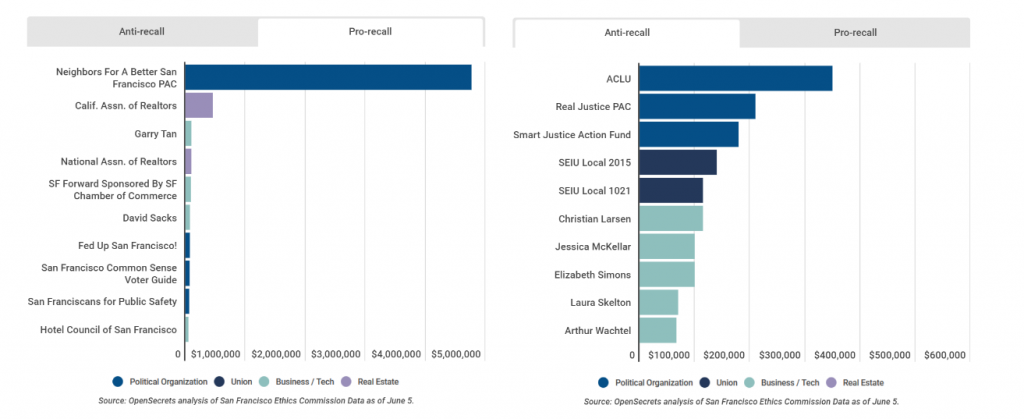

Greenberg doesn’t see this barrage of cash as a problem. Rather, he sees it as democratic—people speaking with their wallets, testing out political experiments on a small scale, in areas like San Francisco. Donors use local political action committees, similar to SF Guardians, to funnel donations in from outside of San Francisco. One of them, a little-known, yet colossally funded PAC named Neighbors For A Better San Francisco (NFABSF) has been a goliath in this field. NFABSF has been the largest sponsor for many local campaigns, such as Boudin’s recall, all while being made possible by hundreds of thousands of dollars in out-of-state donations.

Contributions by donor for Prop H, the recall of District Attorney Chesa Boudin. Source: OpenSecrets

Reviewing the website for NFABSF, only two things can be learned: that they are neighbors and that they want a “better San Francisco.” One of those is false. NFABSF seems to be flexible on who is a “neighbor,” and who should have a stake in local politics.

Take donations leading up to 2022’s midterm elections for example. On August 19 of 2022, NFABSF received a $50,000 donation from James and Cecilia Herbert of Jackson, Wyoming. Kilroy Realty gave NFABSF $50,000 on October 6, 2022, following that up with another $25,000 twenty-one days later. On October 17, NFABSF received $100,000 from Arash Salkhi, a gas station owner in Marin County. Betsy and Robert Reiner, of Hailey, Idaho made a $100,000 dollar contribution to NFABSF on October 27. Most shocking of all was a $300,000 donation from Silicon Valley billionaire William Oberndorf, an active political contributor who has bankrolled Republican candidates all over the country.

San Francisco has strict election contribution policies. Candidates for elected offices, such as Supervisor, or Mayor, are bound by a $500 dollar campaign individual donation cap. Those small individual donations, and small amounts of public campaign funds, make SF elected official campaigns relatively inexpensive.

For a supervisorial bid, campaigns can cost “approximately $350,000,” Ahsha Safaí, Supervisor of San Francisco’s District 11 (whose office initially declined an interview), told me over text. This is in contrast to other large California cities, where individual donations cap out at $1,600 and campaigns cost upwards of $3.3 million.

But what is not protected against is the economic might of seemingly local political action committees. “Often, elected office campaigns have independent PACs support them,” Supervisor Safaí explained to me. Safaí stressed that these PACs act independently of the candidate, and cannot coordinate at all with the campaigns they support. But, nonetheless, PACs like NFABSF remain vessels for insurmountable amounts of campaign contributions.

If outside spending can influence multiple recall elections at this scale, then San Franciscans must beg the question of who has power in their city. Is it the voters, who turn out at a rate of below 50% in off-year elections? Or is it the donors, who bankroll the creation of propositions, then purchase their way to victory?

And what remains?

A broken city, crumpled by the desires of unaffected donors.

Research Assistance by Henry Donald.

Featured Image: DALL-E

Comments are closed.