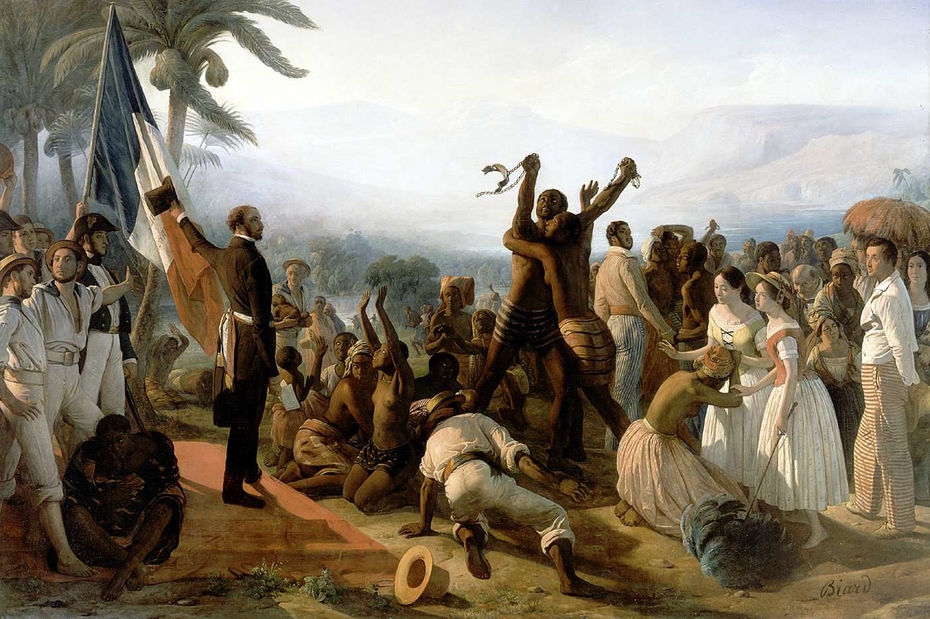

The transatlantic slave trade and the exploitation of enslaved African laborers in the Americas stand as one of the darkest, most horrific pieces of the history of Western civilization. Without the motive, the means, the organization, and the dedication of European colonial powers in establishing and perpetuating this system of slavery, the modern world may have looked quite different. Europe, in the wake of growing global recognition of the legacy and continued existence of systematic racism, is finally beginning to open its eyes to the real consequences of its actions in centuries past. However, there is little to no urgency amongst European leaders to atone for their nations’ crimes, with even basic apologies seeming a step too far for some. The issue of how states can or should repay the victims of slavery is a highly complicated one, and not one I will attempt to provide a definitive answer to in this article. But if it is difficult for the perpetrator to even acknowledge the pain they have caused, what hope can there be for justice?

Festering Wounds

Between the early 1500s to the mid 1800s, roughly 12 million Africans were captured and transported across the Atlantic Ocean and forced into labor in the Western Hemisphere. For those who survived the voyage through the “Middle Passage” – which claimed the life of roughly 20% of the enslaved captives – the conditions in the Americas were incredibly grim. Granted no pay, no freedom, no education, and living and working in conditions unfit for any human, enslaved Africans labored tirelessly to line the pockets of white businessmen, and to produce luxury goods for the white middle class. They were subject to arbitrary and horrific violence, were bought and sold like cattle, and were routinely separated from their families and loved ones. Of the Africans brought to the “New World”, nearly 6 million were on Portuguese ships, primarily destined for Brazil. Another 2.3 million were transported by the British to their Caribbean colonies, nearly 1 million were taken to British North America, and the French imported an additional 1.3 million to their Caribbean holdings.

The continued legacy of slavery is, as has been well-established, very visible today. It is no coincidence that Haiti, a republic formed following a successful slave rebellion, is today the poorest country in the Western Hemisphere. Its status as a republic created and led by formerly enslaved persons made it ripe for centuries of exploitation, extraction, and imperialist meddling by the likes of France and the United States. Many of Haiti’s neighbors in the Caribbean, where 40% of enslaved Africans were transported to, suffer from similar economic troubles, endemic poverty and hunger, and poor levels of public health, education, and houselessness. In Brazil, the country that received more enslaved persons than any other, Afro-Brazilians make up two-thirds of incarcerated individuals and 76% of the poorest segment of the population, despite only accounting for just over half of the nation’s total population.

This rampant inequality and societal underdevelopment is a direct consequence of the system of slavery built and operated by European states. The harms done are so substantial that it is incredibly difficult to imagine what could be done to ameliorate them. But the first step to take is to acknowledge one’s responsibility for the harms, something Europe is struggling to do.

The Long Walk to Recognition

Relative to the almost two centuries of total silence on the issue, definitive progress is being made in Europe towards recognition of their role in the slave trade, and potential efforts at reconciliation or restorative justice.

In 2020, the European Parliament took a significant symbolic step by declaring that slavery was “a crime against humanity”. Just this year, the European Union adopted a joint declaration, along with the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC), expressing “profound regret” over the “appalling tragedies” and “abhorrent barbarism” of the slave trade. The statement, given hesitancy from several European leaders, stopped short of committing to reparations, but did make a reference to CELAC’s Plan for Reparatory Justice, which delegates from the organization had hoped would be more firmly adopted.

Portugal, the nation responsible for exporting the most slaves and historically among the least willing to acknowledge its role in the slave trade in its education system, monuments, and popular culture, has also taken a significant forward. In April, Portuguese President Marcelo Rebelo de Souza said that his country needed to formally apologize for its role in the slave trade, and to “take responsibility” for its actions. Though he offered no specific plans for how to go beyond an apology, such a step would be rather monumental, as no nation in Europe apart from the Netherlands has ever issued any formal apology. Unfortunately, these examples stand in stark contrast to the actions of other European states, namely France and the United Kingdom.

In 2001, France became the first country in the world to recognize slavery as a crime against humanity via an act of parliament. The law, as it was originally drafted, opened the door to limited, individual reparations, but this section was cut from the final version. In the decades following, appeals to French courts for reparations have been roundly dismissed on the basis that plaintiffs have failed to show “direct, reparable harm” done to them by French slavery. Perhaps more disturbing is France’s failure to seriously consider reparations to its former colony Haiti. The Haitian Republic, only years after it gained its independence from France following a successful slave revolt, was forced by the French government to pay for the debt caused to French businessmen who lost their slaves, or to submit again to French rule. Between 1825 and 1947, Haiti paid the equivalent of between $20-30 billion to France. This massive wealth extraction directly contributed to the country’s rampant poverty and social disorder that has it currently in crisis. French governments have repeatedly dismissed accusations that they owe Haiti anything for ransoming their freedom, and references to this piece of French history are largely absent from education curriculums and scholarship. Last year, the Foreign Ministry told the New York Times that “France must face up to its history,” but dismissed calls to calculate the total amount of money it received from Haiti, retorting: “That is the job of historians.”

In the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak echoed this tone, claiming that Britain should “[understand] our history and all its parts,” while simultaneously arguing that “trying to unpick our history is not the way forward.” He is also staunchly opposed to considering reparations, in spite of a recent International Court of Justice report that suggested that the UK may owe at least $24 trillion in damages for its promotion of slavery. Meanwhile, King Charles III has commissioned an independent study into the British monarchy’s historical links to the slave trade. The King has expressed his profound sorrow over slavery and committed to learning more about his family’s ties to the practice, but has stopped short of acknowledging that any links do exist, despite significant public knowledge of past monarchs’ role in the slave trade.

What Will it Take?

To say that your nation must “face up to” or “understand” its history, but then to dismiss efforts to determine the legacy and impacts of that history as “the job of historians” or “not the way forward” is utter nonsense. They acknowledge that a problem exists but reject any semblance of responsibility for it. Of course, the likes of Rishi Sunak, Emmanuel Macron, and any other modern European leader did not directly participate in the institution of slavery. Whether or not their ancestors benefited from this institution, the institution they are charged with representing and leading – their country – owes much of its modern stature, success, prosperity, and power to the commodification, dehumanization, mutilation, and genocide of millions of Black Africans and their descendants.

An apology is the bare minimum anyone can ask for when harmed by someone else. Thus, the reluctance of European nations to so much as officially admit wrongdoing is rather astounding. But exactly why is acknowledgement so difficult? Two primary answers present themselves. One, European leaders and states are just racists who refuse to see themselves as owing anything to Black and brown people. Or two, European leaders are afraid to acknowledge the reality of their country’s past because they are afraid of what obligations that will create in the future.

I do not think that the first of these two explanations universally holds true in Europe, though racism and prejudice certainly remain real obstacles to justice. That is why I find the second explanation most compelling. Rishi Sunak fears apologizing for the U.K.’s role in slavery, not because he does not think it was a horrible mistake, but because acknowledging that mistake seemingly acknowledges the obligation to rectify it. Modern France may believe that forcing Haiti to pay reparations for its freedom was absolutely lamentable, but the thought of paying billions of dollars to an impoverished nation in crisis, and taking responsibility for the proper distribution of these funds, is far more repulsive.

These compulsions are understandable. Everyone wants to preserve the status quo, especially one that is personally beneficial. But so long as the current status quo persists, the consequences of slavery will continue to be lived out, everyday, by millions and millions of people. Conveniently for white Europeans—and Americans, it should be said—the problematic reality of slavery is a fact of history, one that can be ignored or addressed at will. For the descendants of those enslaved, and for anyone else living in a nation whose colonial-era wealth was built upon the institution of slavery, this problematic reality is a thing of the present and future. So long as the will to apologize is so weak, the will to implement real restorative justice will be far off. The world is moving in the right direction, but there are millions if not billions of people for whom justice and compensation are already far too late. For the time being, it seems likely they will remain elusive.

Featured Image Source: Useum

Comments are closed.