What does it mean to be a worker in America? This is the fundamental question at the heart of the United Auto Workers’ strike.

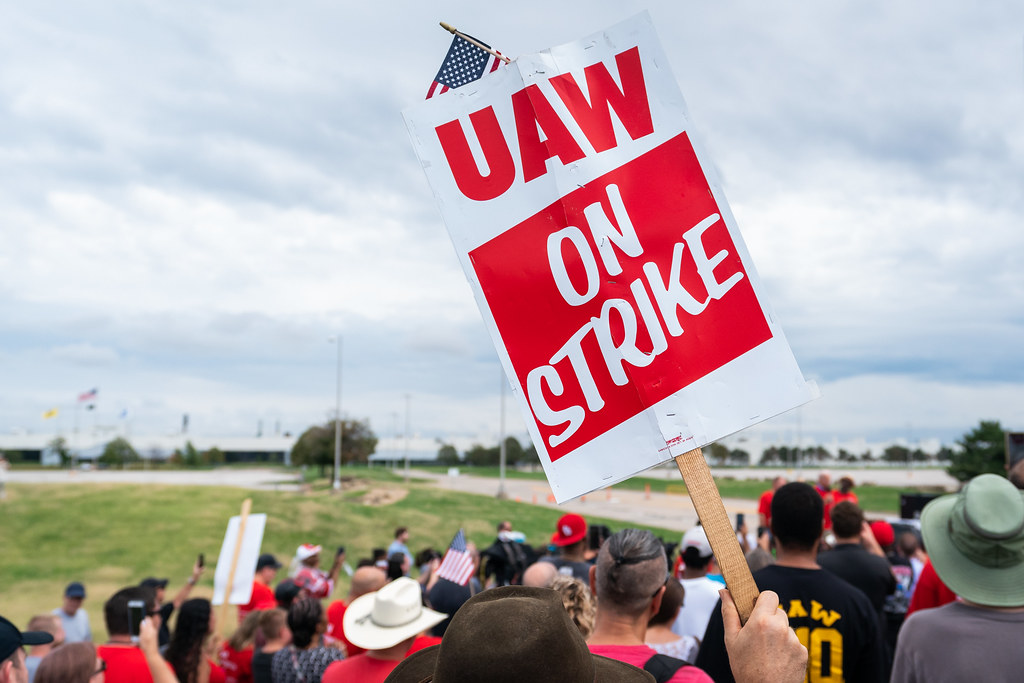

On September 15 the UAW made history by simultaneously striking each of the Big Three auto manufacturers: Ford, General Motors, and Stellantis. The move comes off the back of Shawn Fain and the militant wing of the UAW changing union leadership by winning the March 2023 International Executive Board elections.

While the UAW may not be the largest union in America, it is arguably the most influential in the public eye. When Americans think of blue-collar manufacturing work, the type of work that created the middle class, few would ignore auto-workers in the Midwest. Thus, when the UAW makes demands and goes on strike, the results have the potential to set a standard for the rest of the nation.

With the ability to set a national standard, it is worthwhile to view what the actual demands are. The UAW is asking for a 36% increase in wages over 4 years, restoration of pensions, an end to two-tiered wage status, the return of cost-of-living adjustments, a 32-hour work week with 40 hours worth of pay, and job security guarantees amid the electric vehicle transition. A 36% wage increase over four years seems substantial; some would even call the ask outrageous. In a vacuum, it may seem that way, but when a decade’s worth of context is added, the big ask becomes considerably more justifiable if not outright deserved.

In 2008 the UAW agreed to take a haircut on wages and benefits in order to help bail out the Big Three Auto-makers during the Great Recession. In the 15 years since, the Big Three have fully recovered, garnering a combined $21 billion in profits in the first half of 2023 alone. Over the past ten years, the auto companies have seen combined profits to the tune of $250 billion. The CEOs of the Big Three have seen an average of 40% increase in their compensation packages over the past four years.

So where does this leave the UAW?

On the whole, the UAW has seen a decrease in real wages when you account for inflation. While the CEOs saw massive increases in their compensation, the UAW obtained only a 6% wage increase over the same four-year period. To paint an even clearer picture: Ford CEO Jim Farley makes 281 times more than the average Ford worker, General Motors CEO Mary Barra makes 362 times more than the average GM employee, and Stellantis CEO Carlos Tavares makes 365 times more than the average Stallantis employee. For context, the average CEO made 20 times more than their average worker in 1965.

The argument made by workers is simple: record profits, record wages. The CEOs and stakeholders should not be the only ones to reap the rewards—the blue-collar workers who make it all possible deserve a larger piece of the pie.

What workers make after they finish their careers is arguably just as important as what they make during their careers. One of the concessions made in 2008 was that all new union members would receive a 401k instead of a pension. The current strike looks to overturn that change and restore pensions for current and future UAW members.

The main benefit to a pension plan compared to a 401k would be that the employer is the primary funder of the former while the employee is the primary funder of the latter. In either system there can be a combination of the two funding one’s retirement plan. While some would argue the flexibility and individual decision-making associated with a 401k is superior, a pension plan provides stability and dependability, making pensions much better suited for retirement. More importantly, the workers themselves are fighting for this type of benefit.

The two-tier wage system is more union-specific, but still has implications for what other unions may fight for in future strikes. Longstanding union members receive better benefits and wages while newer members receive watered-down compensation packages. An example already mentioned can be found in pensions as opposed to 401ks: members before 2008 got to keep their pensions while new hires were forced into a 401k.

The two-tier system has historically been used as a tool to slowly wean unions off of better benefits. Newer members cannot be angry over not receiving benefits they never had while older members can be satisfied with keeping their original benefits. UAW members are now showing an extreme sense of solidarity in advocating to end the system, though. Workers who can still receive the greater benefits are fighting for those who lack them. This goes beyond the individual, it is a fight for workers and the union way of life.

The fight for cost of living adjustments (COLA) is something familiar to the Berkeley campus. The GSI strike last fall was heavily predicated on the need for COLA in an environment of inflation and ever-rising housing prices. The same is true for auto workers in the Midwest, albeit to a different degree.

The fight for a 32-hour work week on 40 hours of pay is not one of just compensation but of redefining what it means to be a blue-collar worker in America. A hundred years ago it was uncommon to see a 40-hour work week. The idea that people would have a standardized work cycle was ludicrous, almost too much to ask for. Yet here we are. A 32-hour work week seems unfeasible now, but it only takes one union to start the normalization process.

The UAW is making big asks in these negotiations, but each one is logical and worthwhile. Redefining what it means to be a blue-collar worker is not easy, but it’s a fight we should all get behind.

Featured Image: Adam Schultz / Biden for President

Comments are closed.