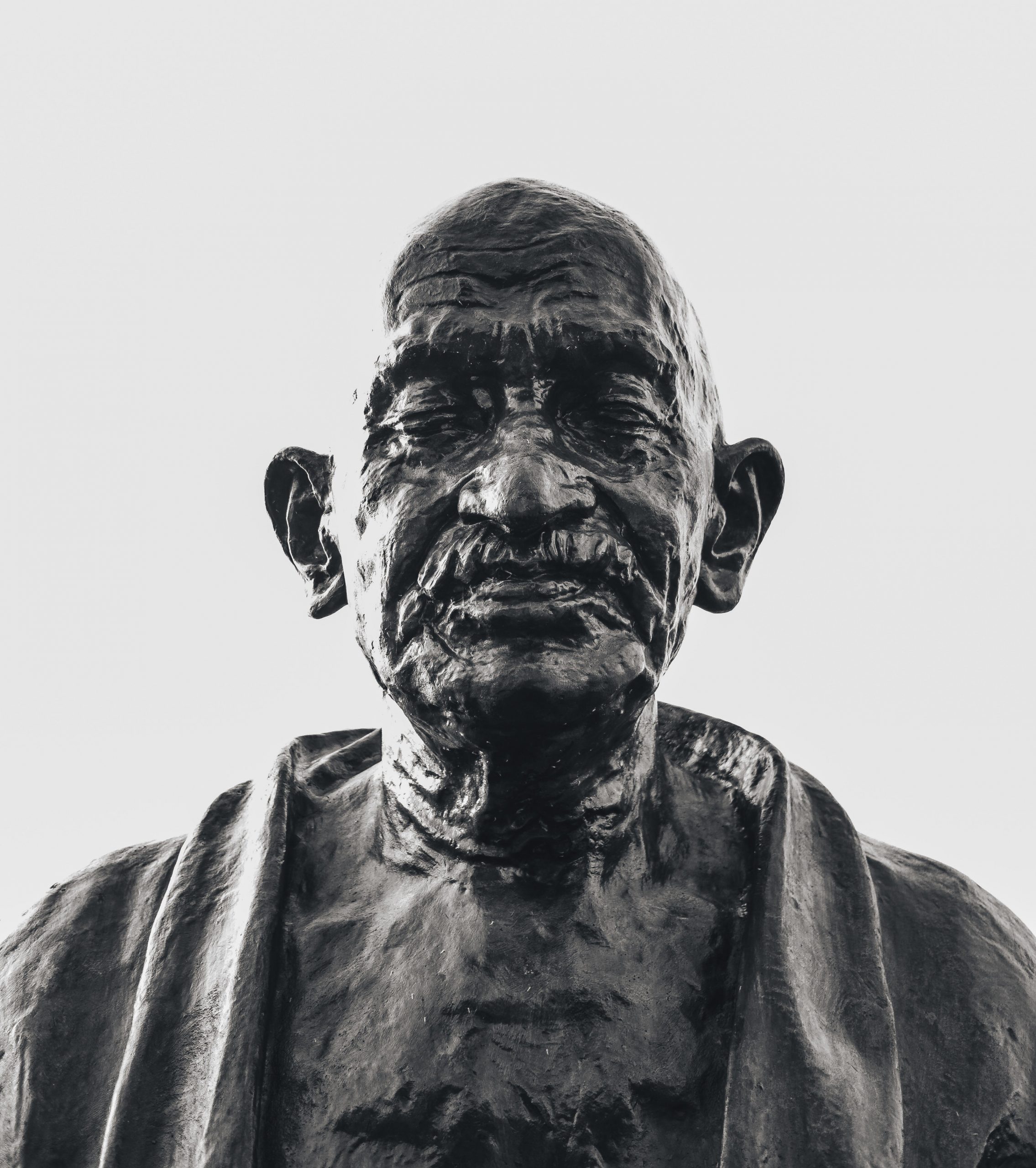

Clinging onto hope is a core tenet of the Quranic scripture, a book that Ulemas (Islamic Jurists)—who, as everybody knows, represent 100% of Pakistan’s population— believe form the basis of all institutional & civilian structures in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. But latching onto false hope for the coming of a Mahatma (Great Soul) like Gandhi is against the principles of the Ulema too. The Mahatma is a myth. It is a folklore created to exalt a politician who, like all politicians, was human, but arguably one of greater faults than the rest. Their concealment serves to disillusion the masses, who idly wait for a Mahatma to appear or seek one in every political leader.

Having grown up on a diet of Gandhi hagiographies, I was appalled to learn the truth of his days in South Africa.

In legends, Gandhi’s quest for equality began when he was thrown off a first class “white-only” train cabin in Pietermaritzburg, South Africa. In common accounts of the infamous incident, storytellers often omit the actual arguments Gandhi advanced to achieve his aim of “equality”. He did not take a stand for all parties facing prejudice, as many believe now. In fact, it was the opposite. Gandhi was upset that he was being treated as part of the native black community. This, he contended, went against the rules set out by Queen Vicioria’s 1858 proclamation stipulating equal treatment for traveling British subjects, by virtue of being representatives of the imperial mission in foreign lands. His disdain at being treated as ‘black’ and ‘native’ continued through his time as a member of the Natal Indian Congress (NIC) in South Africa, an elitist body funded by rich Indian merchants.

Gandhi’s first success as a part of the NIC was his triumph in the “Durban Post Office dispute.” The office had two entrances: one for blacks and one for whites. Gandhi disliked this system: how could Indian men so superior, purer, and higher in stature enter through the same gate as the natives? In a letter to the legislative assembly of the NIC, Gandhi asserted that Britishers and Indians “spring from a common stock, called the Indo-Aryan” and through being forced to enter with the South African, “(the) Indian is being dragged down to the position of a raw Kaffir (infidel).” For Gandhi, such a preposterous arrangement was unacceptable and a third entrance, exclusive to Indians, was the only solution. Gandhi got his third segregated door.

Mahatma was not done yet. He was committed to cementing the “Imperial Brotherhood” between the Indians and the British. An opportunity arose in 1906, when the British went to war with the Zulus, the largest ethnic group native to South Africa. Gandhi, the supposed freedom fighter, volunteered for active service to deny the Zulus the right to live in and control their ancestral land. He had previously been a member of the Indian Natal Ambulance Corps during the Boer war fought between the Dutch and the British, but disinfecting the wounds of his colonial oppressors had not, in his eyes, sufficed to prove his racial superiority to the native African.

In a letter published in the Indian Opinion, a Gujarati-English newspaper Gandhi founded in 1903, he opined that “at the time of the Boer war it will be remembered that the Indians volunteered to do any work that was entrusted to them and it was with great difficulty that they could get their services accepted even for ambulance work.” In 1906, Gandhi wrote again in the Indian Opinion, this time campaigning for Indian enlistment in the British army to crush the Zulu Rebellion: “It is not for us to say whether the revolt of the Kaffirs (infidels) is justified or not. We are in Natal by virtue of British Power…It is therefore our duty to render whatever help we can…we believe what we did during the Boer War should also be done now.” British and Indian soldiers killed 4,000 Zulus approximately.

Gandhi characterized this chapter of his life as “Satyagraha in South Africa” in his autobiography, “My Experiments with the Truth.” “Satyagraha” is a Gandhian invention promoting the practice of “Non-Violence” at all instances of his Civil Disobedience Movement. In his book, his objectively violent actions take a completely different form as inspirations for celibacy and poverty: “While I was working with the Corps two ideas which had long been floating in my mind became firmly fixed. First, an aspirant after a life exclusively devoted to service, must lead a life of celibacy. Second, he must accept poverty as his constant companion,” and more potently, “We had to cleanse the wounds of several Zulus which had not been attended to for as many as five or six days…We liked the work. The Zulus could not talk to us, but from their gestures and the expression in their eyes they seemed to feel as if God had sent them our succor.” Many history pundits turn a blind eye to these racist words and actions, chalking them up to Gandhi’s past and claiming his political philosophy had yet to fully develop.

Knighting himself as the flag bearer of socialism in India, his “experiments” with poverty, celibacy, and asceticism were funded by Birla, an Indian industrialist. Portraying himself as the only sane voice in India demanding equality—a highly ironic claim in light of his past—he never denounced the Varna Caste System that divides Hindus into a strict status hierarchy. Indeed, he actively supported it. He was an avid supporter of Hindu Muslim Unity and Akhand Bharat (unified India) and, in sermons at his ashram (religious monastery), he reflected nostalgically on ancient India as a time when its soil had not been corrupted by the “Mohammadeans (Muslims).”

There is no Mahatma in politics. Especially in Pakistan. The Pakistanis have to learn to treat every politician as a flawed human, capable of deceit, falsity and lies. The Republic has been butchered in the name of men who were considered the Mahatmas and prophets of the modern age many a time. Zia-ul-Haq, Pakistan’s military dictator from 1977 to 1988, is remembered as a great Muslim by many. Why a great one? He galvanized support in the backwaters of the Federally Administered Tribal Areas up north in Pakistan by selling a false Jihadi slogan to the impoverished. It was more popular than Afim (Opium) that is brought in from across the border into the region. Many were on their way to Afghanistan to fight the Soviets, the “infidels,” to save Islam, answering the call of the protector of Islam. If the civilian base would have questioned his motives then, it would have become clear that he was no messiah, just a crook who sold his people in return for US-Gulf aid. Most of the aid went into “deep pockets,” “Jihadi Camps” and, what was left, was used to build the Faisal Mosque in the capital city of Islamabad. Zia rests in a nice abode outside the idolatrous monument, much less a mosque. Even in his death, he cannot but serve as a thumping reminder that he fooled us. And fools we continue to be, walking giddily around the shiny edifice of the mosque laying blood-red rose petals on his grave.

The Pakistanis have been entrapped in the Mahatma complex too many times. Every once in a relatively short while, a new face comes along, bedazzled with the same jewelry, just in different places—and the Pakistanis drool at first sight. The newcomer beats the same drum to the same tune as his predecessors. People are entranced and start to move to it. Soon enough, they latch a newly minted tag to the person’s neck, ranging from “Mahatma” to “The greatest” to the “Father of the Nation.” What matters more than the specific label is the immunity it gives the newly knighted. No fingers can be lifted to question or probe the new hero. Where did he get his jewelry? Why does he wear it the way he does? And why is it always a “he”? If one raises an eyebrow and asks the questions, they are shut off by the drum, which beats faster and louder now, than before. The jewelry signifies a renewed Pakistan, one that shall have zeal and fervor. The tune of the drum is the slogan of Islam. The signifier of a promise that Prophet Muhammad’s name shall be securer than earlier, that God shall protect the people, the state and Zia’s mausoleum more now. All questions targeted at the orientation of the jewelry can be shut off by the drummer. Always. As did the Mahatma with a different drum and a unique tune whenever anyone poked at him.

A nation shall always regress socially if it makes a “Great Soul” out of everyone who has the drum. Pakistan does not have a good track record, with a knack of awarding medals to those who play it too well. Take Mumtaz Qadri, a cold-blooded murderer who shot Salman Taseer in 2011. Salman was a politician embroiled in a media war against the right wing at the time for speaking up against the Blasphemy Law that disproportionately targets non-muslim minority groups. Every year, thousands pay a visit to his tomb at the outskirts of Islamabad for his heroics the day he killed the “heretic” in broad daylight, when he should have been protecting Salman as his bodyguard. One cannot meaningfully protest against his actions in the political arena of modern-day Pakistan because of the immunity the tag, the jewelry, and the drum give him. As a result, pertinent issues are swept under the rug and parasites like political indifference, extremism, and ideological crises persist.

The drum may be beaten for as long as people pay respects to Mumtaz and Zia. We are the ones who have to break out of the trance and shatter the myth of the many Mahatmas that weigh down on us, our history and lay bare all truths that escaped us. For, as the proverb goes, ‘fool me once shame on you; fool me twice shame on me.’ Never shall a Mahatma fool us again, for one shall not exist here onwards.

Featured Image Source: Pexels

Comments are closed.