Western society has become entrenched in finding solutions to climate change that fit into a colonized understanding of the world. Much of Western academia operates on the widely-held assumption that the Anthropocene Epoch has led to the current climate crisis and the solution to climate change lies in reverting the world to how it was before the epoch began in the 1950s. However, many Indigenous people all around the world, specifically the Māori tribes of Oceania, have been preaching a contrasting point of view. They believe that the Anthropocene ignores the role of colonialism in environmental degradation, and they argue that returning land back into Indigenous hands, restoring their cultures and self-determination and acknowledging Indigenous voices when creating climate polices will help ease the crisis.

How is Western Climate Policy Rooted in Colonialism?

In the early 2000s, the term Anthropocene Epoch became the prominent line of thought to explain the extent of damage to the environment that had occurred as a result of human occupation and enterprise. The expression emphasizes how the great acceleration of human activity has led to an increase in the concentration of carbon dioxide and other gases in the atmosphere, higher surface temperature, ocean acidification, biosphere degradation, deforestation, and international tourism, all of which have negatively impacted earth systems due to humans’ domination over the land, air and oceans. This epoch is thought to have begun as a result of an underlying human need to pursue capitalist gain at the expense of the environment and Indigenous lives, societies, and self-determination. Such ideals of modernity and progress within the capitalist system, at the expense of many Indigenous cultures, have created the current climate crisis.

Debates have occured over when, specifically, the Anthropocene period began, but it is largely held that it was pioneered in the 20th century among largely white academic spaces in the Global North. However, several Indigenous scholars have rebuked the term. For instance, Jessica L. Horton, a scholar of modern and contemporary art and Indigenous studies and politics at the University of Delaware, has critiqued the Anthropocene through her art collection “Indigenous Artists against the Anthropocene,” which aims to bring attention to Indigenous peoples who have persisted through white supremacist systems that threaten both the environment and Indigenous communities. In this context, she has evaluated the shortcomings of the Anthropocene as a theory. Horton and many other Indigenous scholars argue that the notion of Anthropocene is built on the claim that universal human nature has created the current crisis and ignores the central role of colonialism, a system that, as Horton describes, a “minority of humans created and other humans powerfully resisted.” The Anthropocene label thus excludes the effects of colonization on the climate crises and denies the history of people who have been exploited by colonial institutions.

Other Indigenous academics have drawn a connection between centuries of racial capitalism and settler colonies to the modern climate crisis. Colonial imposition has been a violent invasion of the earth, sky, and sea and a means of subjugating lands, humans, and non-humans to maintain colonial relations and garner capital. For several hundred years, European intellectual development led to the genocide of Indigenous peoples and the perversion of their lands.

What Does it Mean to Decolonize Environmental Justice?

Decolonizing environmental justice means changing the Western understanding of human-nature relationships. The Western materialist tradition is rooted in “desacredizing” the universe. In the name of progress and development, Russel Means, an Oglala Lakota political activist, posits that Western colonizers were able to take “piece of the sacredity of human existence and convert into an abstraction.” There is no longer any satisfaction to be gained from simply observing the wonder of a mountain or a lake or a people in being. The European colonial mindset so deeply imbedded within people socialized in the West forces us to see the mountain as gravel, the lake as coolant for a factory and people as a laborious means of production. Satisfaction is measured in terms of gaining material.

In a practical sense, we must envision and develop a world in which Indigenous climate-led solutions are at the forefront of conversations about climate change and in policy-making and legislative circles. Colonial structures in place must not only acknowledge, but actively reallocate their resources in order to offer support to existing Indigenous systems. This will require the deconstruction of current oppressive systems to create space for Indigenous peoples to have their own independent and self-determinative societies built around a balanced approach to the climate crisis and a respectful and reciprocal relationship with the environment.

In short, we must return their land.

The Māori Tribe as a Case Study of Indigenous-Led Climate Policy

The Māori people arrived to modern-day New Zealand around roughly 1300 AD and, up until the arrival of European settlers in the 1800s, they lived in small tribes with a rich, vibrant culture featuring spoken stories and traditions of warfare. The Māori’s relationship with their ancestors and the natural world was of paramount importance, and they recognized a link between humans and the environment. This connection is expressed through ‘kaitiakitanga’, a way of managing the environment based on the Māori world view that humans are an integral and equal part of nature. This belief system, this intimate relationship with the land, and this understanding of their place in nature means that they usually have a very deep respect for nature and practice systems that support conservation and sustainable use of resources.

The arrival of Europeans from the early 1800s had a major effect on these early communities. Among the newcomers were missionaries, and many Māori were forced to abandon the culture of their ancestors and succumbed to Western traditions and religion. The Treaty of Waitangi signed in 1840 established British law and government, but it could not prevent warfare in the 1840s and 1860s as Māori defended their lands and local authority. After the wars, Māori lost land through confiscation and sale, mostly to British settlers. Today, the Native people of New Zealand make up a mere 16.5% of the population

Furthermore, modern anti-climate change policies are influenced by pre-existing colonial biases. These biases in environmental policy are perpetuated with policies that dispossess local communities from their land in the name of producing renewable energies or label traditional uses of land as a threat to conservation. Climate policies continue to exclude Indigenous people worldwide even though they are disproportionately affected by rising sea levels and extreme weather events. For example, the Māori people of New Zealand have not only had their land taken from them, but are also disproportionately affected from climate change. Their specific impacts include loss of culturally significant structures and places, access to equitable resources, cultural traditions, and practices. Since many of the Māori people were forced out of their traditional lands into sub-optimal living areas, such as river or coastal floodplains, climate-crisis-induced phenomena such as flooding, coastal erosion, and storm surges are more likely to harm Indigenous peoples. Rural communities also do not have steady access to safe drinking water and are more susceptible to the effects of droughts. The climate crisis has implications in many other practical sectors of life for indigenous people such as poorly serviced water and sewage systems, decreased agricultural productivity, and increased job insecurity. On a cultural level, many Māori have strong cultural and historic affiliations with coastal lands in Aeotorea that will be affected by rising sea levels, and traditional uses of the land such as gathering food will be interfered as planting seasons are unpredictably shifting due to climate change

The Māori people have, fortunately, made minor strides with regard to implementing Indigenous-led climate policy. For example, the New Zealand government created an initiative with the goal of achieving self-determined and Indigenous leadership over ocean climate change. The ocean initiative supports Māori to protect and monitor New Zealand’s coastal waters and high seas in partnership with local communities, using both traditional approaches and modern science. Efforts will focus on marine conservation and providing direct benefits to Māori tribes and coastal communities, from jobs to infrastructure. In addition, the initiative will also establish a marine recovery plan with Māori to accelerate the recovery of populations of taonga species, which are species that were present in New Zealand prior to European contact with the Māori in the 17th century.

The efforts of the Māori people should inspire other Indigenous communities around the world to mobilize and aim to create solutions to the climate crisis that follow Native tradition in the sense that they respect nature and utilize their knowledge of practices that support conservation and sustainable use of resources. In addition, non-Indigenous people and governments should include Indigenous voices in climate action and policy projects.

In Conclusion

Colonialism was motivated by the premise of plundering the environment and subjugating populations, and the pervasive and persistent institutions of colonialism make it far more challenging to address the climate crisis and implement solutions in a just and equitable way. However, the Western idea of climate change and modern climate policies ignore the significance the colonialism on the state of the environment.

The Māori tribe of New Zealand represent a marginalized and colonized peoples that have been making significant efforts to unpack the influence of colonization on climate policy. They have created an initiative that works to monitor New Zealand’s coast using a combination of modern understanding of environmental science in combination with their sustainable traditional and cultural practices. By observing the Māori tribe, we can see that the most effective climate policies work with Indigenous people by utilizing their knowledge and respect of the land rather than building of the Western idea of the world by aiming to, contradictorily, exploit the earth whilst also trying to save it.

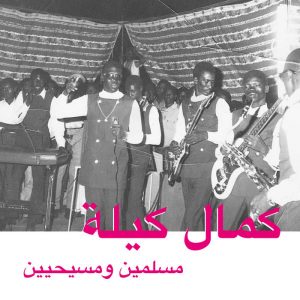

Featured Image Source: Indigenous Climate Action

Comments are closed.