“After all, who can blame a country for being able to take advantage of another country to the benefit of its citizens?”

After visiting Beijing in 2017, former President Trump made a statement that may accurately reflect China’s contemporary foreign policy. Deemed the “Chinese miracle,” China has lifted 850 million people out of poverty since the 1970s. However, this rise to power has not come without international alliances and the exploitation of developing nations. During this period, China has embarked on a strategic journey to strengthen its ties with developing nations, extending its reach far beyond its borders. One notable arena where this diplomatic maneuvering is reshaping traditional alliances is Latin America, a region historically dominated by Western powers, particularly the United States, its neighbor to the north. As China boldly expands its foreign policy horizons, the contours of South-South relations, or relations between developing states, are being redrawn. With a keen focus on economic engagement, China’s outward foreign assistance and trading partnerships in Latin America are challenging the established narrative of development, led by the Western hemisphere, to a new one of conservatism and anti-democracy.

To comprehend the current dynamics at play, it is crucial to understand the historical context of China-Latin America relations. The region of Latin America has experienced exploitation from colonial powers since the 1500s, much of which has endured into the modern day. Upon and following the conquest of the Americas, indigenous societies were forced to subscribe to European rule. In many cases, this dismantled local economies, subjugated indigenous people to inhumane working conditions, and nearly eradicated native cultures. Although many colonized states gained independence in the 18th and 19th centuries, histories of colonialism led to corruption and poverty within these newly sovereign states.

Post-independence, the United States harshly shaped the political formation of many Latin American countries. Through conditional aid and other forms of informal influence, the U.S. pressured these countries to enter the global market, which often destabilized local economies. In an attempt to struggle with such crises as a result of legacies of resource exploitation and lack of institutional foundations, many states in the region have developed undemocratic, even autocratic, governments.

During the Cold War, many Latin American countries became ideological battlegrounds, fighting American and USSR influence both socially and economically. Still, despite attempts to rival American control, Latin America has largely been a sphere of influence for Western powers, with the United States at the forefront of political and economic engagement and acting as the main provider of foreign investment to the region.

However, in recent years, China has strategically pivoted toward developing nations, aiming to foster South-South cooperation. Launching the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in 2013, China officially set out its goals to increase its outward foreign direct investment to developing regions such as Africa and Latin America. This shift represents a clear departure from the conventional North-South paradigm and offers Latin American nations an alternative avenue for development. In some ways, the growth of the Chinese model in opposition to the Western model is forcing many developing states to pick a side in manners reminiscent of the Cold War. The evolution of China’s foreign policy, marked by the BRI and other collaborative frameworks, signifies a departure from the traditional dominance of Western powers in shaping the global order. This historical comparison underscores the significance of China’s engagement in Latin America.

China’s economic interests in Latin America are multifaceted, extending across various sectors such as infrastructure, energy, and technology. China has become South America’s top trading partner and the second in Latin America to the United States. From 2000 to 2022, trade between the regions grew from $12 billion to $315 billion. Unlike the Western model of development that often comes with conditions, Chinese investment is characterized by a non-interference approach, providing Latin American nations with more autonomy in decision-making. Yet fewer conditions have driven many states, like Venezuela, into “debt traps,” or a situation of ensured economic dependency to China. As China rapidly and exponentially deploys loans to the region, countries accept the aid but are unable to effectively repay the conditions, leaving many of China’s aid recipients on the brink of economic upheaval.

An analysis of major sectors targeted for investment reveals a strategic alignment between China’s needs and Latin America’s resources. The extraction of natural resources, infrastructure development projects, and technological collaborations form the cornerstone of Chinese economic engagement. As of 2023, Beijing has free trade agreements in place with Chile, Costa Rica, Ecuador, and Peru, and 21 Latin American countries have so far signed on to China’s BRI. The sheer scale of Chinese investment has the potential to transform industries and economies, presenting both opportunities and challenges for the recipient nations.

While economic expansion serves as a manifestation of China’s presence in Latin America, its implications extend far beyond trade balances and infrastructure projects. The economic influence wielded by China translates into political power, challenging established diplomatic norms and alliances. Employing a culture of soft power, China is attempting to extend the sway of the Chinese Communist Party indirectly through policies like BRI. As of October 2021, China has established 28 Confucius Institutes in South America located in Brazil, Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Venezuela. These institutes serve as locations for Latin American students to learn Mandarin and Chinese diplomacy, and in some cases offers scholarships to study in China. Since 2015, China has participated in three summits with leaders and foreign ministers of the Community of Latin America and Caribbean States (CELAC), a region-wide organization that excludes the United States and Canada.

As a result of such economic and cultural exchanges, changing political dynamics are observable through shifts in diplomatic alignments and international relations. China ranks countries like Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Mexico, Peru, and Venezuela as diplomatic allies in terms of its strategic Latin American partnerships. The Center for Strategic International Studies claims that it is no mistake that states with the closest ties to China have some of the most anti-democratic political regimes. A study by this organization finds that China spreads its model of authoritarian governance through soft power engagements in the media, education, and people-to-people diplomacy, which directly contributes to the backsliding of democracy. It also provides economic and diplomatic support to regimes that are experiencing democratic backsliding, even as these governments grow steadily separated from the rest of the international community.

Such democratic backsliding is evident in countries like El Salvador, Brazil, Venezuela, and Nicaragua. A range of motives underpin China’s involvement in these states, but the most prominent reasons include the possession of natural resources, growth of renewable energy industries in the area, the region’s proximity to China’s rival superpower United States, and the aim to bolster Chinese assertiveness on a global scale. Within El Salvador, China contributed substantial economic investments and have continued these investments amidst and in support of strongman President Nayib Bukele’s reign and consolidation of power. In Brazil, controversy arising after the election of President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has revealed Brazil’s interest in China-led regional blocs aimed at challenging the existing liberal systems in the state. In Venezuela, a country previously riddled with autocracy and human rights violations, China has provided continued investment in the state’s oil and security industry, regardless of this support’s implications in preserving anti-democratic structures of power. Lastly, in Nicaragua, China provided highly-centralized and authoritarian leader President Daniel Ortega with bountiful investments in infrastructure projects. Such investments were continued even during extreme human rights abuses and sanctions imposed upon the state.

Each of these examples elucidates Chinese anti-democratic attitudes. While China has not directly impacted a reformulation of political structures, it has provided support and investment to authoritarian regimes and to economic sectors that perpetuate human rights violations.

Although many Latin American states are accepting and utilizing Chinese foreign aid, their political structures have not changed dramatically. It is the states that have already struggled with democracy that are adopting the Chinese model of state-led capitalism. Nonetheless, while the political changes may not be robust, trading partnerships are major. China is South America’s primary trading partner and has grown consistently since their entrance into the World Trade Organization in 2001. Therefore, China may not be actively shaping the political composition of Latin America, but rather reinforcing and enabling existing antidemocratic structures.

As China continues to expand its global footprint, the region may witness further evolution in economic and political relationships. The potential for increased collaboration, enhanced diplomatic engagement, and regional integration could shape a new era of South-South cooperation. However, the diffusion of Chinese soft-power into Latin American society is actively unraveling democratic institutions and instead enabling a culture that promotes authoritarianism and, in some cases, tyranny.

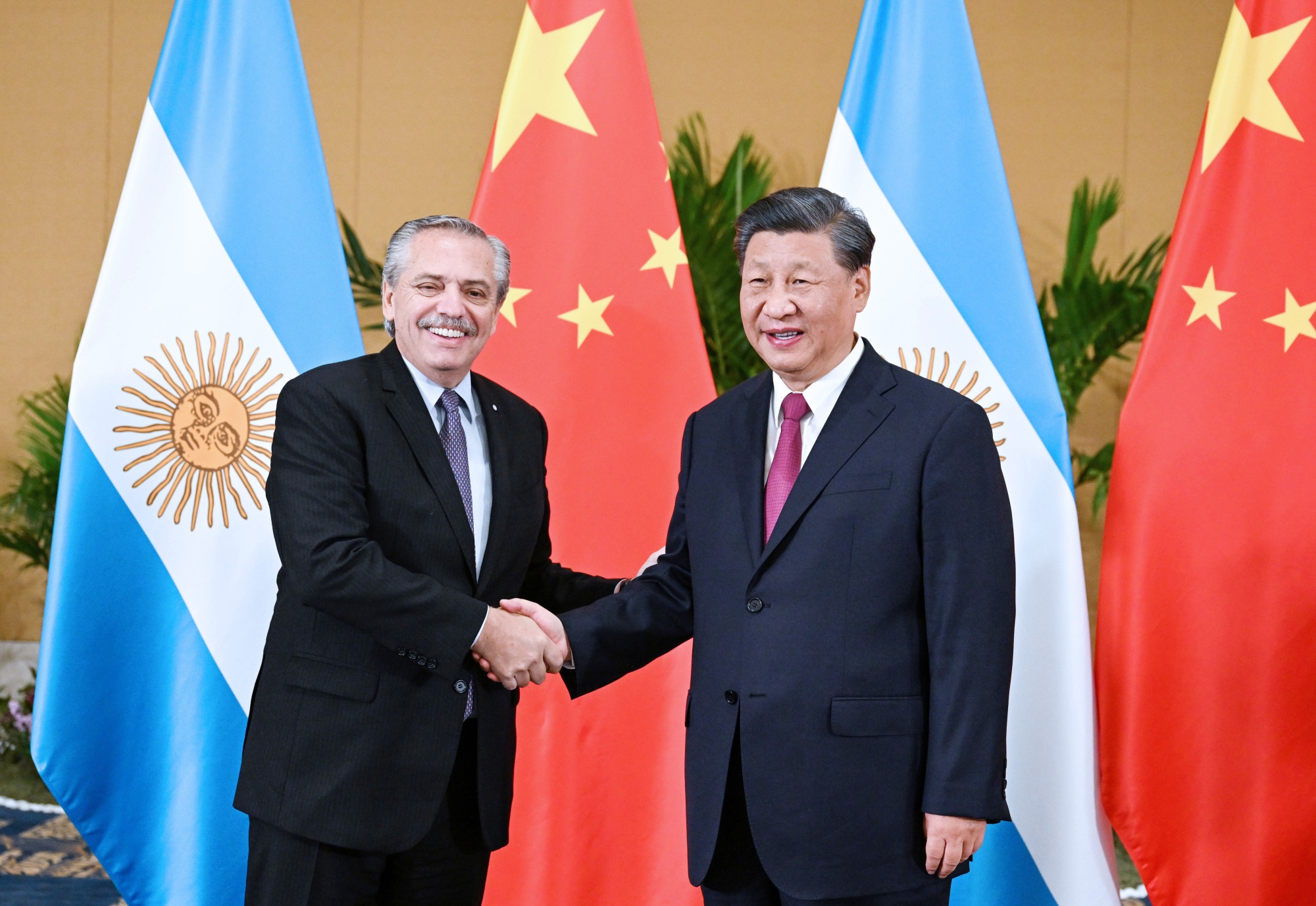

Featured Image Source: Bloomberg

Comments are closed.