Every year in northern France, between the popular tourist venues of the Opal Coast and the cold Flemish beaches at the border with Belgium, thousands of people hide behind dunes and between bushes waiting for the sun to set. When the sky is dark and the air still, they drag on the shore precarious embarkations—commonly known as “small boats”—and cross the English Channel, leaving France for the United Kingdom. This channel crossing is yet another obstacle in the course of a migrant’s quest for survival.

According to Oxford’s Migration Observatory, 11,434 people on the move arrived on the English shores between January and June 2023. The influx of undocumented migrants seeking to reach the U.K. has significantly increased since 2020, when Great Britain exited the European Union. In doing so, the country broke from the Dublin Regulations, one of the main European immigration treaties stating that each illegal migrant ought to remain in the first EU country of arrival. Thus, hundreds of people arrive every day at northern France’s two largest refugee camps, the Calais “Jungle” and the Grande-Synthe encampment, waiting to be smuggled by unreliable “passeurs” in overcrowded and crumbling embarkations.

Although the refugee camps are located at the center of the two cities’ urban areas, local and national administrations ignore their inhabitants. Aside from the police’s multiple forced evictions, the authorities never set foot in the camps, neither to provide them with tents and blankets during the freezing winter season nor to distribute food, water, clothes, or phones. These duties are entirely left to English, French, and international NGOs, which collaborate to ensure that migrants’ primary needs are met. Naturally, because of inherent budget limitations and organizational capacities, it is impossible for these organizations to assist more than 45,755 people—based on data from 2022 —per year.

In 2022, I spent the last part of my summer holidays volunteering in the refugee camp of Grande-Synthe with the French NGO Utopia56. The association was born in December 2015, when pictures of the two-year-old Syrian child Aylan Kurdi lying dead on the beach, having drowned en route to Europe, were circulating in the news, leaving many horrified. After spending a weekend volunteering in Calais, co-founders Yann Manzi and his wife, Gaëdig, were struck by the lack of French NGOs operating in the refugee camp and created Utopia56, which today has nine branches throughout France. In Grande-Synthe and Calais, Utopia56 adjusts to the changing necessities of refugees, taking care of emergencies of any nature arising in the camp and on the neighboring beaches. Every day, we assisted families, unaccompanied minors, and individuals in their daily quest for survival. While Utopia56 was responsible for bringing migrants to the doctor, calling ambulances, checking the beaches at night to make sure they were empty of people in need of help, and spreading safety information to keep in mind during the sea route, Refugee Community Kitchen (RCK) distributed hot meals and Refugee Women’s Center took of care of women and families’ safety.

Despite the collective efforts, the health and safety conditions at the camp are extremely poor. In the Grande-Synthe refugee camp, migrants are forced to sleep outside, with temperatures plummeting to 35° Fahrenheit during winter nights. NGOs are equipped only with a limited amount of tents and sleeping bags, which they assign first to families and unaccompanied minors, hoping that enough will be available to cover the needs of everybody else as well. During the summer, high temperature levels worsen the extremely unhygienic conditions of the camps. Thus, infectious diseases such as scabies spread at a record rate and they prove to be hard to eradicate. Despite the high count of scabies cases and dental infections, the Dunkirk Hospital’s “PASS”, the French term to describe a hospital’s branch dedicated to undocumented people, is open only three days per week, and the dentist office opens its doors to migrants two times per month.

Moreover, the lack of basic services forces people to put themselves in dangerous situations. On August 9, 2022, a Sudanese boy drowned while swimming in a basin near the encampment. During that week, RCK’s communal showers, which are usually available every other day, had broken down, leaving the refugee camp’s inhabitants without the possibility to access clean water to wash themselves. One week after, while I was driving to Dunkirk’s hospital, I glimpsed down to the basin and found three of the boy’s friends swimming in the same place. Had the local administration intervened, by financially sustaining RCK in replacing the shower truck, migrants would not have needed to test their swimming skills by washing themselves in the basin.

European states consider refugee camps as autonomous enclaves in their territory, whose existence is undesired but inevitable and whose inhabitants should not expect any kind of assistance from the outside. However, this relationship is characterized by a major exception: law enforcement agencies. Police interventions are, in fact, very frequent within both the Calais and Grande-Synthe refugee camps. According to a 2020 report drafted by three local NGOs—Human Rights Observers (HRO), the Auberge des Migrants, and Help Refugees (Choose Love)—the number of evictions in Calais increased from 452 in 2018 to 961 in 2019. HRO has highlighted multiple times the illegality of these evictions: oftentimes, the police officers destroy or take possession of the migrants’ belongings, while they should only temporarily confiscate them and give them back whenever the owner claims them.

I indirectly witnessed several such instances. One day, I was sitting on a shopping cart turned upside down when a Syrian man approached me and, with the help of a virtual translator, communicated that the antidepressants that he had been taking for the last months had been confiscated by the police in the previous week’s raid. He wanted to ask me if the pills that he had found close to his tent could have been a good replacement. The harm inflicted on the man was clearly not limited to his impossibility to access his prescribed treatment as this spurred him to find alternative medicaments, whose unknown nature constituted a potential danger.

To ameliorate the precarious living conditions in which refugees live at Europe’s borders, specifically at the Franco-British border, two main courses of action are crucial. First, a greater amount of public budget should be allocated to projects designed to meet the needs of undocumented people permanently or temporarily stationed in European refugee camps. Many such initiatives already exist and are entirely run by local NGOs, however, they could greatly benefit from additional funding and support. For example, migrants stationed in the camp sleep in tents when NGOs can provide them; thus, their living conditions would greatly improve if the government helped fund permanent buildings to house them. Current efforts to provide temporary housing to migrants already exist thanks to the refugee assistant organization Afeji Hauts-de-France and to a net of local households, but, because of spatial limitations, these are almost exclusively directed to unaccompanied minors, fragile people, women, and their families.

Moreover, new projects that go beyond the NGOs’ reach should be put in place. These can take the form of partnerships with Dunkirk’s dentists, psychologists, and hospitals to ensure a broader service for undocumented people or the establishment of a permanent phone charging station inside the Grande-Synthe refugee camp. The former policies would address one of the main problems affecting migrants en route in Europe: mental and physical health. People on the move are often victims of human rights abuses such as torture, beatings, sexual assault, and rape which can take place in their home country, throughout their journey, or in Europe. Currently, the psychological scars left by such experiences are greatly neglected, and there are no systematic programs designed to provide psychological support to undocumented people. In Dunkirk, the “PASS” is equipped with only one psychologist available a limited number of days per week. However, given the high demand for mental health assistance and the undeniable superiority of French private psychologists’ network over the public one, the French state should partner with local private mental health professionals who, through virtual meetings, can assist their patients also when they leave Dunkirk.

Second, governments should establish a more thorough “policing” of law enforcement agents. Associations like HRO have limited power and resources to effectively monitor the police’s actions and to impede them from breaking the law; hence, the state should actively intervene in this process, building a system of accountability for its law enforcement agencies. It is intolerable that migrants are stripped of their right to private property and that the French government never investigates the unlawful grounds underlying refugee camps’ evictions. A national ombudsman holding French law enforcement agencies to account for their actions directed specifically to undocumented people should be established. Again, this should not substitute current NGOs’ projects, rather, it should support them with additional resources and political leverage, and complement them by expanding their reach.

At the border between France and the U.K., like in other European borders, the state’s conscious neglect of migrants’ rights, coupled with the police’s unlawful actions to keep undocumented people from crossing invisible lines, is one of the main causes of their deaths and precarious living conditions. To effectively address these circumstances, it is necessary to hold European states accountable for their inaction and to spur them to implement concrete public policies aimed at the improvement of migrants’ lives both in refugee camps and in their desired destination. Such policies should adapt to the specificities of the context in which they are going to be implemented; for this reason, governments should collaborate with local NGOs, whose years of field experience will prove to be crucial in upholding the dignity and humanity of all migrants.

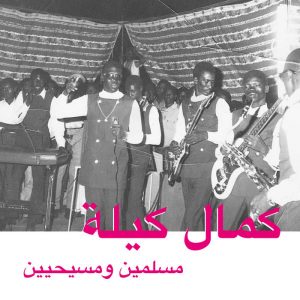

Featured Image Source: HuffPost

Comments are closed.