At the dawn of the 20th century, failing dictatorships and crumbling empires left millions of people vulnerable to poverty, hunger, war, and extermination. The “free” world, with all its graciousness, has aided tens of nations to alleviate their suffering. Statistically, numerous humanitarian assistance projects, which the Western bloc primarily manages and funds, have shaped the world we live in today. The U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) helped save more than 30 million children in Africa through its aid projects to end hunger; the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA) spent 29 billion dollars on humanitarian assistance in 2023 alone; and the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) and the European Union (EU) have supported Ukraine with 80 and 5 billion dollars, respectively, in lethal and humanitarian aid since Russia’s invasion of the country in 2022. However, as Bruce Bueno de Mesquita and Alastair Smith point out, when aid does little good in the world, it causes much more harm.

To seek a better understanding of this controversial dilemma, BPR spoke with Professor Martha Wilfahrt, Assistant Professor at the Charles and Louise Travers Department of Political Science at UC Berkeley. Professor Wilfhart teaches and researches the political economics of development.

One of the first efforts of humanitarianism, Wilfahrt believes, is the British Anti-Slavery Movement, which is largely attributed to the founder of the former British Province of Georgia, James Edward Oglethorpe, who convinced the British Parliament to ban slavery in Georgia between 1735 to 1750. The movement shows one of the earliest signs of exerting resources for a foreign cause. In this case, the Anti-Slavery Movement publicized much of its anti-slavery rhetoric to eventually influence the Abolition Acts of 1807 and 1834 which emancipated 800,000 slaves across the British Empire.

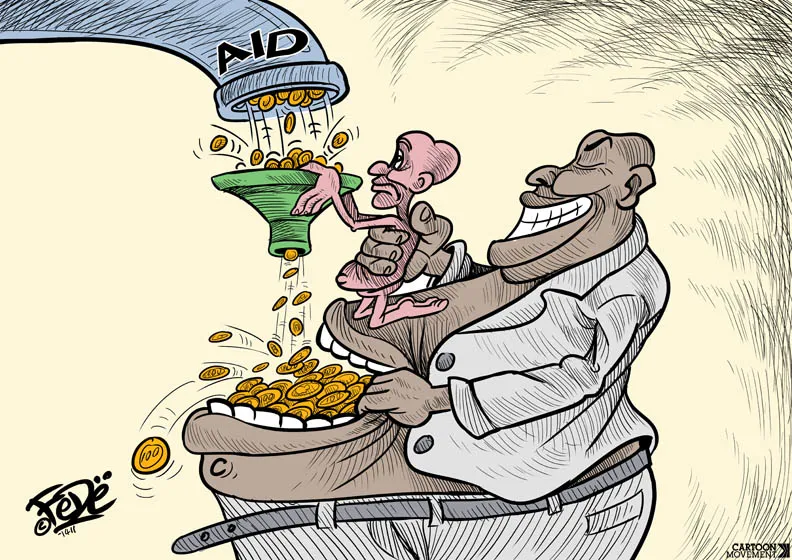

But foreign aid can be extremely harmful, too. In 2002, a junior public servant in Kenya reported cases of corruption in the deals made between some Kenyan politicians and Angle Leasing Finance. The U.K.’s commissioner in Kenya would later accuse the entire government of corruption and bribery going as high as the President, Mwait Kirbaki, when 11.5% of the national budget came from foreign aid. More recently, after the 2020 Beirut Explosion in Lebanon, many countries surprisingly decided to restrict or withhold any aid to the Lebanese government. Between 1193-2012, Lebanon received over 170 billion dollars, which is equivalent to the entirety of the Marshall Plan, with no improvement in the economy, infrastructure, or basic needs. By 2022, UN agencies alone donated 300 million dollars to the Lebanese government, which is a quarter of Lebanon’s annual spending. However, this unfettered flow of aid inspired a leading elite class that separated itself from the suffering of the public while depending on international aid to pay for “public education, health care, social assistance, security, and more—even sponsoring partial salaries for teachers and soldiers.”

The fact is, the Lebanese government waited for the aid packages to come after every crisis to take their share and keep the country running just well enough until the next crisis. The government, for example, has staunchly objected to foreign aid appropriated to NGOs, which they claim could transform the state into the “Republic of the NGOs.” However, it is this same government that perpetrated such unprecedented levels of dependency and corruption that the need for NGOs exists in the first place. Lebanon is not the only country to deceitfully petition for humanitarian aid just to keep its administration favorable and unimpeachable enough.

Today, foreign aid is almost always used as a tool for the donor country to achieve some level of influence within the recipient state. The Emergency Trust Fund for Africa, for instance, is the EU’s migration management tool to regulate uncontrolled migration flows. With a promise of more than 5 billion Euros in development aid, the regional body has funded multiple developing countries to help them accommodate a larger influx of immigrants and regulate their route towards Europe. However, the recipient states often use that aid to further persecute the refugees and strengthen their grip on power.

Why do States Give Foreign Aid in the First Place?

Scholars have largely accepted the U.S. Marshall Plan as the first action to grant foreign aid from one state to another. However, there appear to be two beginnings to the story of aid: one that precedes the modern nation-state world, and the other is the Marshall Plan after World War II. The reason why some historians have started studying aid projects before the Marshall Plan is to understand the older forms and motivations of this aid, which was influenced by the primitively anarchical world of the time, according to Daniel Markovits, Austin Strange, and Dustin Tingley. The first evidence of said assistance dates back to 464 BCE when Sparta, an ancient city-state in now Greece, received 4,000 soldiers and engineers from the Athenians as a supplementary backup to help the Spartans resume their fight with the Helots.

In almost all cases of foreign assistance before World War II, the absence of international cooperation only allowed for “gifts:” less politically oriented in the sense that the aid did not go from one state to another, but rather from one leader, or leading party, to another. Over time, as the nation-state system started dominating after the Peace of Westphalia, the decision of aid grants started decentralizing, and the new states started prioritizing political factors in making their decisions on awarding foreign assistance.

The Marshall Plan, on the other hand, constitutes the first evidence of modern foreign aid for its precedence-setting process of implementation, conditionality, scale, and underlying motives. The Foreign Assistance Act of 1948 appropriated approximately 13.3 billion dollars—equivalent to around 170 billion dollars adjusting to 2024’s inflation rate—to help rebuild 18 countries in Western Europe. The aid package, competing with the more aggressive Morgenthau Plan, was split between grants and loans, where around 1.5 billion were allocated for repayable loans. The Plan was marginally different from the traditional “gifts,” including multiple conditions set by the U.S. government for domestic and international interests. For example, recipient countries drastically increased their trade relations with the U.S., and that includes an increase in American exports. American intentions also had a political side behind the motivations; the U.S. leveraged the aid provided by the Marshall Plan to contain Communist movements in Europe and influence other states’ decisions. In 1949, for instance, the U.S. threatened to withdraw all aid from the Dutch government if it did not cease colonial authority in Indonesia after the Indonesian National Revolution.

Since the end of the Cold War, numerous humanitarian catastrophes and military conflicts forced an unprecedented need for development and humanitarian assistance. When the institutional aid network expanded to circulate more than 168 billion dollars annually in 2021, the motivations, structures, and success rates of aid diversified as much. Today, there are more than 30 ongoing armed conflicts, 828 million people still facing hunger daily, and tens of humanitarian crises. Aid conditionality, Wilfhart affirms, has evolved to fall under two central categories: ideological homogeny and foreign policy strategy. However, a new trend to setback aid—or at least remove the “humanitarian-oriented” aspect from aid packages—has been emerging globally as the international political atmosphere is transforming.

Ideological Hemogony: France’s Neo-colonial Aid to Former French West Africa

Despite France’s efforts to distance its government from accusations of neocolonialism, the French government has long held onto its last reins of imperialist practices through “stabilization” aid. From one side, France, as of 2021, has been awarding African countries around 4.7 billion dollars in aid per year. On the other hand, until that same year, fifteen West African countries, members of the Francafrique, were required to keep 50% of their currency reserves in the French treasury. Even though the French economic development system helped the recipients maintain lower inflation rates than most other African countries, the financial dependence on a democratizing France has only further alienated the West African state, and forced them into state breakdown and Russian alignment.

After Burkina Faso’s two coup d’états in January and September of 2022, for instance, the junta—the Patriotic Movement for Safeguard and Restoration—has adopted an anti-French and anti-Western stance, proclaiming that Russian aid is much safer than colonial-infused French assistance. Since the outbreak of the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria (ISIS) insurgency in West Africa, many of the African countries’ governments have shown massive failure in protecting millions of their citizens from displacement. In Burkina Faso, Paul-Henri Sandaogo Damiba, the leader of the first 2022 coup, implored then-President Roch Kabore to hire Russian private militia, the Wagner Group, to fight the insurgents. As Kabore strongly rejected the recommendation, citing the West’s potential outrage at such a plan, the public, influenced by the military, further deviated from any support to the civilian government, and rather saw a military coup as the final step for decolonization.

Professor Wilfahrt believes that the economic and security issues of the Sahel countries, including Burkina Faso, are far more nuanced to be exclusively attributed to the French government’s actions. While she asserts that the French post-colonial influence is undeniable, she remains “skeptical of claims that all the problems French West Africa are because of France.” Rather, African “elites,” Wilfahrt explains, marginally contributed to the failed economic takeoffs in more of the countries in that region through corruption, bribery, and bureaucratic dysfunction. She further explains that the CFA Franc monetary system—the recently reformed French-controlled monetary system in West and Central Africa—has been a “stabilizing fact of those economies,” unlike what the current revoluting governments believe, which is that CFA has merely been a colonial tool to seize the former colonies’ financial sovereignty.

In West Africa’s case, it seems like development aid, especially one provided by the former Western colonial powers, is a contributing factor to the recurring economic and national security setbacks in the region. However, claiming this aid is the exclusive reason why countries like Burkina Faso are in the state they are in right now is a populist narrative used by junta leaders to justify overthrowing weak governments.

‘Humanitarian-exit:” The Massive Abandoning of the Humanitarian Part of Assistance

After a few decades of a humanitarian boom and a shift towards thinking of aid as a general international duty, the new ‘humanitarian-exit’ nature of foreign assistance has minimized the humanitarian factor in aid and focused on national foreign policy agendas. Jan Egeland, then-Under-Secretary-General for Humanitarian Affairs and Emergency Relief Coordinator, recalls that back in 2005 when he urged Zimbabwean President Robert Mugabe to allow the UN to supply the 700,000 unhoused citizens—because of Operation Murambatsvina—with tents, Mugabe replied that he did not want the world to know that such a crisis is happening under his watch in the first place. Today, this notion of putting unsubstantiated political agendas ahead of urgent humanitarian considerations has only been widespread.

Since 2015, numerous European states faced an overwhelming wave of refugees fleeing wars and disasters. The once migration-friendly countries started deploying less humanitarian-oriented assistance and more controversial “solutions.” With more than 1.3 million refugees coming from all over the Mediterranean just that year, the EU switched to adapting more nefarious policies like its deal with Türkiye, for example. For an exchange of 72,000 Syrian migrants and 6 billion euros in “aid,” Türkiye agreed to accept more than one million rejected asylees who were transported from Europe. Multiple governments and international organizations, including the UN, eventually criticized this “refugee exchange” deal as an outright violation of international laws. Later in 2016, the EU would be forced to suspend its deal after Türkiye’s undemocratic response to the 2016 attempted coup against Erdoğan’s regime.

Today, with the rise of more far-right governments around Europe, especially in countries bordering the Mediterranean Sea, more strict immigration policies are being signed into law every day even in the once most immigrant-friendly states in Europe like Germany. The European Commission’s “Migration Management” agenda, for many humanitarians, is the continent’s first step to abandoning humanitarian causes, which could eventually lead to an isolationist European response to ongoing conflicts like the ones in Ukraine, the Middle East, former Soviet nations, and the Balkans, to name a few. Some scholars even accuse the EU of indirectly consolidating Erdoğan’s authoritarian regime with such aid for purposes of securitization.

Wiflahrt agrees with the idea of a “refugee aid recession,” yet she is also skeptical of how much uninformed blame has been placed on European countries for responding to the “domestic pressures that regimes are facing.” There has been a rapid setback, she explains, in aid and support for refugees even in the most urgent cases like Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Sudan. She counterargues, however, by discussing how the refugee influx is also “extremely stressful” with very “high needs,” which, in some part, justifies Europe’s subsequent response. When European leaders were initially willing to try and accommodate resettling refugees, they were never willing to try for that many people. Along with the rise of the far-right national parties and the center parties’ hesitancy to face the right, Europe is adopting a new approach to solving migration issues: legislative whatever is most popular in the polls and “solves the problem.”

Where is the West’s Aid Headed?

Out of all the humanitarian disasters infecting the world today, two have particularly taken the front page of global news: the wars in Ukraine and Palestine. Ukraine, for instance, has suffered from lagging, poor-quality European weapons while worrying about a complete halt on American aid by the current House of Representatives. As Putin allegedly plans a new winter offensive, the low performance in capacity expansion and aid flow may subject Kyiv to invasion. Similarly, many of the Western donor countries have been under intense pressure from pro-Israeli and pro-Palestinian citizens who have been protesting these states’ funding of both Israeli military development and humanitarian aid to Gazans. The United States has pledged 121 million dollars in aid to the Gaza Strip by the end of December 2023, and just on March 2, the American military dropped 38,000 meals on Gaza. Similarly, Germany has pledged around the same time that it would donate 50 million dollars to aid Palestinians. At the same time, the US House appropriated 14.5 billion dollars, along with the annual 3.3 billion, to Israeli military funding, and the German government has exported 323 million dollars worth of weapons to Israel, which is ten times more than all German defense exports approved in 2022. In the end, those same governments are currently under scrutiny from their citizens who think that no aid should be allowed in Gaza without Israel’s approval while others believe that their governments are funding a “genocidal campaign.”

Despite all this, Professor Wilfahrt concludes that the pursuit of neutral aid—that is aid with no attached political motivations—is an impossible mission. “No matter what you are doing, if you say you want to help a community, you have an idea that your change to those people will be desirable to the world. This impetus of change is the core of it all,” Wilfahrt explains. As aid is innately an action of “tinkering in other people’s business,” it seems like the politicization of aid is inevitable, yet this trend has been negatively influencing Western-funded aid, which could eventually hurt the donor and recipient nations.

Comments are closed.