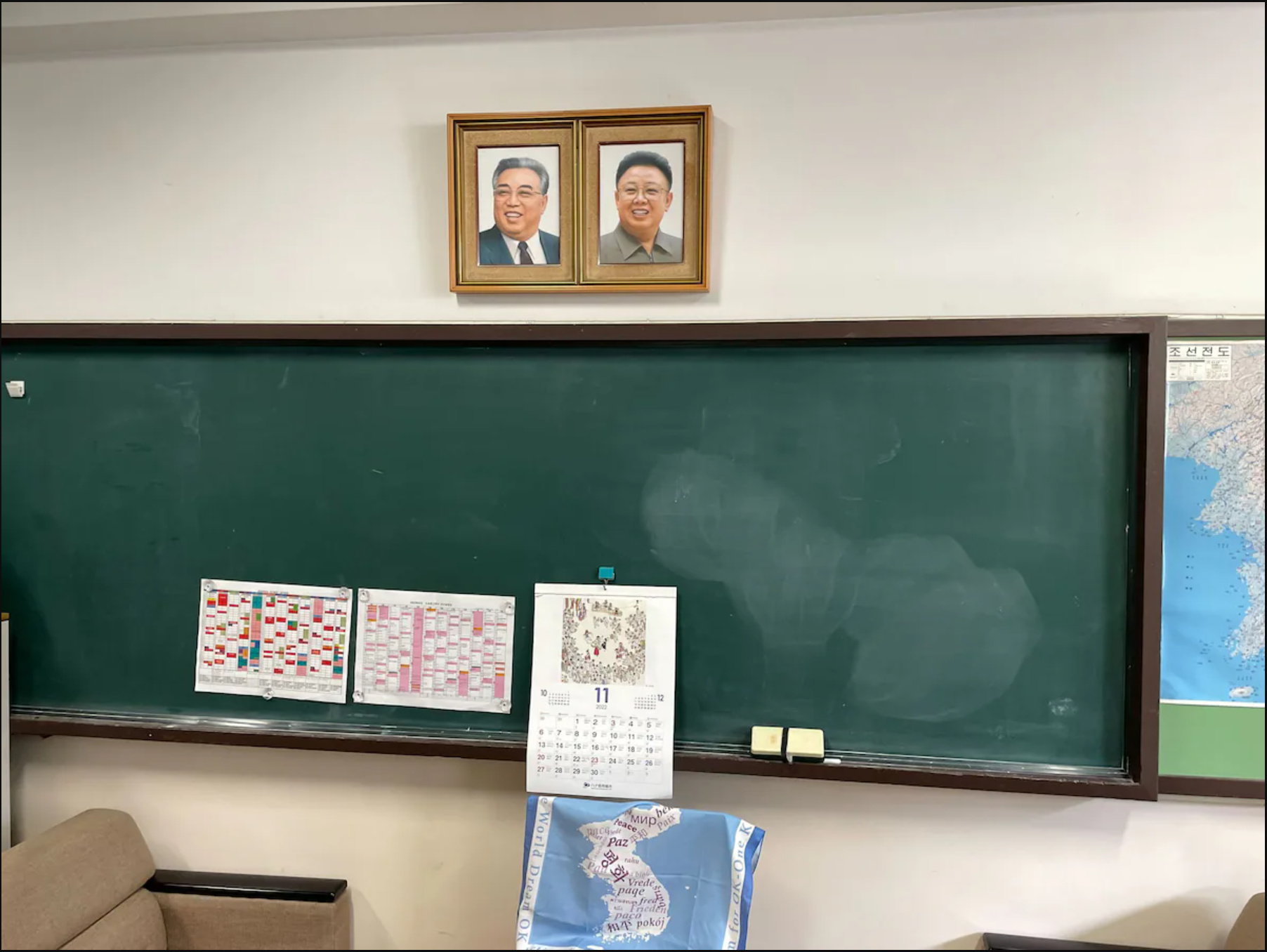

Every morning, in a school located in the heart of Tokyo, high school students change into traditional uniforms, file into their classrooms, and gather under portraits of North Korea’s former leaders Kim Jong-il and Kim Il-sung. Most have never set foot on the Korean peninsula.

This is a school for Koreans in Japan; specifically, those who support Chongryon, an established association running North Korean-funded high schools and even a university. Initially an ideological group founded in response to hostile nativism from the Japanese ethnic majority, Chongryon represented Koreans who found a community identifying with Soviet-backed North Korea, regardless of their actual ancestral ties.

Immigrants in Japan

Prior to the Japanese occupation of the Korean peninsula in 1910, relatively few Koreans lived in the main islands of Japan. However, the Japanese economy began to suffer a shortage of labor in the 1920s, after which scores of Korean immigrant workers migrated to work low-paying, physical labor. Tied together by minority discrimination and widespread poverty, many formed separate communities of their own.

During World War II, labor shortages led Japan to forcibly conscript Korean men and women for manual labor in factories or mines. It is estimated that this led to approximately 239,000 Koreans losing their lives from war-related injuries. Following the defeat, the majority left Japan.

Those who remained were dubbed Zainichi — foreigners ”residing in Japan.” This expression created a perception of the Korean minority as simply residing in Japan temporarily, rather than as immigrants creating a new life in their country. It served to create a harsh division between those ethnically Japanese and ethnically Korean.

After the war, Japanese officials who had initially worked to integrate Korean immigrants into society pivoted to a drastically different response. Post-war Japan began to consolidate its identity as a homogeneous society with ethno-nationalist tendencies.

This continued throughout the second half of the twentieth century. In 1986, the Washington Post reported that the then-Japanese prime minister Yasuhiro Nakasone had “observed” in a speech “that the level of education and intellect in the United States is low because of its large black and Hispanic populations…” as opposed to Japan.

Isolated by discrimination, Korean communities grew increasingly distant from their Japanese neighbors. In response, many Zainichi Koreans joined organized groups that sought to align with one of the two Korean governments, such as Chongryon or Mindan.

As the North Korean-funded organization grew, Chongryon continued to operate North Korean state-funded schools, activities, and others.

“It was North Korea that during the hardest times, in the 1950s, offered their assistance,” says Yu-Sop Kim, the headmaster of the Chiba Korean school. “…We were trying to build schools with very few resources.”

The separation of Korean immigrant society from the Japanese majority created an isolated community with its own educational system. North Korean funding only served as a further motivator to create separate schools and communities for immigrant Koreans, who were then exposed to the propaganda and indoctrination of North Korea. As a result, students brought up largely isolated from outside society began to identify themselves with a foreign autocratic state.

Return to Paradise

Beginning in the late 1950s, Chongryon facilitated the move of around 100,000 Zainichi Koreans, mostly Chongryon members, to North Korea through their “Return to Paradise” program. The generosity of the North Korean government and the pain of second-class treatment in their own country convinced them they were entering a socialist heaven.

Hyangsu Park is one former Zainichi Korean whose relatives moved to North Korea. Years later, Park visited her uncle’s family, only to be told that her uncle was arrested and imprisoned in a harsh labor camp.

“When we arrived, they all started to cry. They were under threat. They told me they might be arrested too. They were shaking.” Later, Park discovered that her uncle had been tortured to death, and the rest of the family was sent to the horrific Yodok concentration camp for “political prisoners.”

“My mum had so much pain and regret,” Park told South China Morning Post. “It’s like being held hostage. We had to be loyal to the North Korean government so we could protect [our families]. We had to be obedient to Chongryon.”

She and her mother never heard from their relatives again.

Many blame the Japanese government for its ignorance regarding the move. South China Morning Post reports that declassified documents reveal Japanese officials discussing ways to convince Zainichi Koreans to leave Japan prior to Chongryon’s migration scheme. Pyongyang facilitated the move, but Tokyo’s ethno-nationalistic beliefs led to willful ignorance of Zainichi Koreans’ fear and grief.

Isolation from Japanese Society

Many members, born and raised in Japan, do not have citizenship due to the requirement to adopt a Japanese last name. They identify with their Korean identity and choose not to adopt a Japanese name. Therefore, they are significantly disenfranchised from participation in politics and voting, receiving little representation in government.

Anti-North Korean activists in Japan have identified Chongryon students, as well as students attending other Korean schools, with the North Korean regime. Cultural disengagement has only widened—as well as discriminatory behavior towards the community.

“The worst thing was being turned away at the blood donation center. I heard the center’s officials say we don’t need Zainichi blood,” said Kim Song-rang, a Chongryon member. “ I was shocked to have heard that.”

Others face discrimination in searching for jobs, difficulties traveling abroad, and bigotry near schools.

“[If I wear my traditional clothing outside] I feel scared,” a student wearing her Korean school uniform told Vox. “People stare at me. I change into it only for school.”

Schools began to place men from their communities at street corners in 2017 on children’s way to school, to prevent students from harassment by those who blamed the community for the recent North Korean nuclear testing.

The government continues to cite actions by the North Korean government as reasons to avoid funding Korean schools. In 2012, the government excluded Korean schools from tuition subsidies due to the ongoing issue of abductions of Japanese nationals by North Korea. The continued association with the North Korean government has prompted discrimination against Korean students.

In 2022, North Korea launched a mid-range ballistic missile over Aomori Prefecture. Chongryon reported at least nine instances of verbal or physical violence against students after the launch. One specific instance had a male train passenger stomp on a student’s feet while criticizing Korean schools for calling for the reinstatement of tuition subsidies. Increased fear of similar harassment has further isolated the community from Japan.

Political Cards

It was the supposed generosity of the North Korean regime that turned many Zainichi Koreans into supporters of North Korea. However, North Korea’s economic collapse after a widespread famine resulted in a significant loss of funding to foreign groups aligned with them.

Chongryon struggled to operate under the loss of funding. Eventually, the Japanese government demanded they repay their overwhelming debt. When Chongryon failed to repay, Japan seized multiple organizational buildings, leaving little but the schools still standing.

In recent years, schoolchildren have faced increased harassment from anti-North Korean activists. “It’s not right to politicize issues that have to do with education and children…” says Kim. “It’s like taking these children hostage to play diplomacy.”

Although many Koreans in Japan now support South Korean organizations, such as Mindan, Chongryon supporters send their children to North Korean schools, participate in North Korea-funded activities, and harbor loyalty to the North Korean regime. The worsening discrimination has continued to perpetuate the divide between Japanese individuals and Chongryon Koreans in Japan. Popular association of Chongryon schools to North Korean aggression results in widespread tensions between ethnic Japanese and Chongryon members.

By continuing to perpetuate separation, supporters of North Korea in Japan will be more likely to consolidate their loyalty to the Kim regime, resulting in continued tensions between Koreans and Japanese in Japan. Japan must address this issue by recognizing Zainichi Koreans as genuine, real members of Japan’s community, rather than temporary inhabitants. By working to create an integrative environment for Koreans, the government can address problems of historical discrimination and discourage present-day xenophobia. Only then will the Korean community truly begin to integrate into Japanese society.

Japan is known as the world’s fifth-largest democracy. However, the Korean community often suffers from disenfranchisement due to their legal status as non-citizens. While more and more Chongryon Zainichi Koreans are obtaining Japanese names and citizenship, many are still stateless. Japan must pursue a strategy of encouraging integration into Japanese communities and society to encourage Koreans to obtain citizenship. By breaking down the walls between Korean communities and Japanese society, Zainichi Korean communities will feel more welcomed by the country they live in and be less susceptible to the North Korean regime.

Featured Image: Portraits of former North Korean leaders over a blackboard at the Saitama Korean Elementary and Middle School in Japan. © 2022 Michelle Ye Hee Lee/The Washington Post.

Comments are closed.