The Big, the Bad, the Un-American…

In 2020, New York Times writer Kashmir Hill set out to answer a salient question: how dependent are we on Big Tech? Working with a technologist, Hill designed a virtual private network that blocked all internet addresses controlled by tech’s five largest companies: Amazon, Google’s parent company Alphabet, Meta, Apple, and Microsoft. The change was drastic: Hill lost access to any site hosted by Amazon Web Services, including Netflix. The loss of Google was similarly debilitating: almost every website uses Google to track users, block bots, and run ads. Until recently, Uber and Lyft relied on Google Maps’ de facto monopoly on navigation. Blocking Meta meant forfeiting Instagram and WhatsApp—difficult, but functionally possible. Because of Apple and Google’s (Android) duopoly on smartphones, she was forced to use the discontinued Nokia 3310, keypad and all. Microsoft was easier to eliminate on a consumer level since it mainly services business customers with Skype and Microsoft Teams; on a professional level, avoiding Google’s GSuite and Microsoft 365 was virtually impossible.

Hill’s experiment showed how indispensable tech giants have made themselves in our daily activities. This is not a fact that we should live with comfortably. The level of market consolidation today evokes Rockefeller-era oil monopolies and the big banks whose collapse triggered the 2008 global financial crisis. Only this time around, we are dealing with companies and products pervading nearly every aspect of our lives.

Put simply, Big Tech’s “Frightful Five” are antithetical to every core American belief. We celebrate entrepreneurship and innovation; they engage in blatantly anticompetitive practices. We pride ourselves on our democratic institutions; they allow foreign actors to meddle in our elections. We value our private lives; they profit off our information. The urgency of the matter is not lost on politicians: regulating Big Tech is one of the few issues with bipartisan support in Congress. Why then, has it taken so long for the American people to notice?

Innovation vs. Anticompetitive Practices

Over the years, Silicon Valley’s Big Five have developed a virtually impenetrable business ecosystem. Consider Amazon’s network of seamlessly integrated smart home devices, or Google’s ubiquitous search engine. Apple too has mastered the art of designing products that keep users safely within its glorified “ecosystem.”

None of this is by coincidence. In August this year, court documents revealed that Google paid more than 20 billion dollars to Apple, Mozilla, and other companies to guarantee its status as the default search engine on their smartphones and Internet browsers. This allowed Google to control nearly 90 percent of the market for search engines in general and 95 percent for mobile devices in particular. District Judge Amit P. Mehta concluded that “Google is a monopolist, and it has acted as one to maintain its monopoly.” Apple has only recently ended its App Store’s monopoly on iOS apps following the passage of EU’s Digital Market Act, now allowing vetted third-party app stores in the iOS environment. This came with a catch: the company added substantial fees for apps sold on third-party stores, which the Coalition to App Fairness criticized as a “shameless insult to the European Commission and the millions of European consumers they represent.”

But perhaps Big Tech’s most harmful practice is “co-opting potentially disruptive startups” before they become competitive threats. Tech giants have acquired more than 400 firms and startups over the last decade, many of which had the potential to disrupt their respective industries. Google bought AdMob and DoubleClick, Facebook purchased Instagram and Whatsapp, and Amazon acquired Audible and Alexa, to name a few. Stymieing competition is an explicit goal for these companies. Before Meta bought Instagram, Mark Zuckerberg wrote to his CFO to float the idea of buying smaller competitors like Instagram and Path, because if they were to “grow to a large scale, they could be very disruptive.” How ironic—this is someone who consistently preaches the gospel of innovation.

Democracy vs. Electoral Influence

In 1913, Woodrow Wilson warned: “If monopoly persists, monopoly will always sit at the helm of the government.” In this day and age this statement rings especially true—though perhaps not in the way Wilson originally intended. Forceful lobbying aside, tech giants’ true political power is much more pernicious.

Meta came under fire in 2016 for various instances of election interference on its platforms. Propagandists leveraged Facebook to turn fake stories—that Pope Francis had endorsed Trump, for example—into viral sensations. More concerningly, Russians posing as American voters were able to sow discord among the electorate by creating online groups and sharing divisive ads and images. These were seen by an estimated 126 million users before and after the 2016 election. As a result, Mark Zuckerberg spent several years on an apology tour, appearing before Congress multiple times to acknowledge his company’s missteps.

The core of the issue is simple. Up to that point, Zuckerberg’s proprietary News Feed algorithm was just an engineering project. He consistently refused to take any form of editorial responsibility. If any changes are made to its code, it is only to reflect some signal that users are demanding change; no human editors are involved. This ethos assumes perfectly rational users, whereas in reality, people are far from it. Research has consistently demonstrated that when faced with diverse sources of information, we lean into our preconceptions and do what feels easiest—we engage with media that confirms our ideas, and avoid what does not. What emerges then is a so-called “filter bubble.” In his book “Republic.com 2.0,” constitutional law professor Cass R. Sunstein warns of the urgent risks posed to democracy “by any situation in which thousands or perhaps millions or even tens of millions of people are mainly listening to louder echoes of their own voices.” Of course, Zuckerberg was always well-aware of this, but as a former Meta executive noted in 2017: “This was never a problem [Zuckerberg] wanted us to tackle. It was always positioned as an interesting intellectual question but not something that we’re going to focus on.”

However, as political scrutiny subsided, Meta has chosen to once again distance itself from politics, reducing the number of employees working on election security and fully disbanding its election integrity team. This year, Zuckerberg also decided not to have a “war room,” which Meta previously used to prepare for elections. This retreat comes on the heels of more misinformation: Donald Trump’s claim that Haitian immigrants in Springfield, Ohio, were eating pets originated in a debunked post on Facebook. The posts have since been shared millions of times. Despite its efforts to step away, Meta will not be able to escape politics.

What’s Next?

Both presidential candidates have largely shied away from regulating Big Tech. This is unsurprising since both platforms have forged close ties with Silicon Valley. Tech companies have enthusiastically supported Kamala Harris since she first ran for California attorney general in 2010. J.D. Vance’s election as a senator from Ohio in 2022 benefited greatly from conservative tech guru Peter Thiel’s $15 million donation. While Trump has expressed his desire to break up tech giants in the past, he was motivated by personal reasons, arguing that these companies have long “colluded” with Democrats. The 2024 Republican platform states: “We will repeal Joe Biden’s dangerous Executive Order that hinders AI Innovation, and imposes Radical Leftwing ideas on the development of this technology. In its place, Republicans support AI Development rooted in Free Speech and Human Flourishing.”

The prospect of real intervention looks dimmer than ever. And as our political leaders falter, Big Tech only continues to grow.

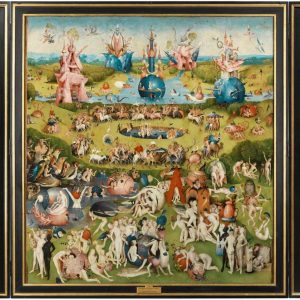

Featured Image Source: New York Times

Comments are closed.