Just a few months ago, leftists and liberals worldwide braced for a grim future. Right-wing parties and candidates across Europe—boasting a common catalog of xenophobia, Euroscepticism, and Islamophobia—were gaining traction. In elections for the European Parliament, these parties rattled long-standing balances. The once-taboo, far-right National Rally (RN) in France trounced President Emmanuel Macron’s centrist coalition, with nearly one-third of the vote. A similar pattern played out in Germany, Austria, and Italy—an ominous warning of national rightward surges to come.

But, in national legislative elections, France defied all expectations and the left breathed a sigh of relief. In calling June’s snap elections, Macron challenged the French people to reject Marine Le Pen’s xenophobic nationalism after her strong performance in the European elections. Surely those results were a fluke. It seems he cockily and naively assumed that French voters would embrace his increasingly unpopular Renaissance party. But when the smoke cleared, things didn’t pan out as Macron hoped. His centrist coalition didn’t win, but perhaps more surprisingly, neither did Le Pen’s RN. The New Popular Front (NFP), the left-wing coalition with whom Macron begrudgingly made a haphazard alliance, emerged victorious with 188 seats.

A disgruntled Macron stalled for two months before finally cobbling together a new government. He named Michel Barnier, a member of the conservative Republicans (LR) party, as the new prime minister. Barnier, who previously ran on campaign promises of mandatory military service and immigration crackdowns, is a far cry from what the French electorate wanted. After all, the center-right, represented by LR, won only 48 out of 577 parliamentary seats.

So, in essence, Macron called the elections to sideline the far right, forging an alliance with the left to do so, then turned his back on the left and appointed a right-wing prime minister.

Treachery aside, however, Macron effectively overruled election results to extend an olive branch to the right. French constitutional convention dictates that the president’s power to appoint the prime minister is symbolic. The prime minister, in true democratic spirit, is meant to come from the party with the most seats—in this case, the NFP, the left. While this is not officially written in the constitution, it is longstanding convention. The betrayal stung and thousands of aggrieved French leftists took to the streets to protest Barnier’s appointment.

Macron does have a history of abusing his presidential powers. Recall the retirement age scandal of 2023, when he invoked the controversial Article 49.3 to bypass parliament. However, his decision to appoint Barnier and exalt the right was ultimately a strategic choice to ensure government stability.

While the NFP won a noteworthy 188 seats—a sign that the French left is alive and well—it fell over 100 seats short of a majority in parliament. France hardly experienced a resurgence of the left, much less a quashing of the right-wing coalition, which holds a not insignificant 142 seats. Not to mention that the RN holds more seats than any other party. In an unruly parliament such as this one, votes of no confidence are a looming, ever-present threat. Macron picked Barnier not so much because of who he is but because he stands a fighting chance.

Perhaps Macron simply didn’t like the NFP’s proposed candidate, Lucie Castets. I wouldn’t put it past him. Being bitter, scornful, and a sore loser would be very on brand, after all, and a leftist victory caught him by surprise.

It isn’t just Macron who resents the NFP, however. While the far left is celebrated in certain elite circles, it elicits contempt and suspicion in most of the French public. Jean Luc Mélenchon’s party, France Unbowed (LFI), is just that—obstinate and disinterested in compromise. Members of the party announced that they would enact “its program, nothing but the program, and all of the program.” Not only does this approach boil down to a contempt for the democratic system, it also breeds a contempt for the left, one that unifies the center and the right.

The NFP is a large coalition, though, and surely could have found a viable prime minister somewhere in the mix. But the coalition was again bogged down by hardheadedness. French leftists bickered among themselves for several weeks, only to land on Lucie Castets: a little-known civil servant with no real governing experience. This obscure choice certainly did not reconcile the NFP with the center. In nominating Castets, the NFP simply slapped a new name on its old stances. And this was not lost on the right or Macron, who immediately rejected her.

Barnier has what the French left does not: palatability. He served as a key Brexit negotiator and, unlike the NFP, cultivated a reputation as a man of compromise. And as a centrist candidate, he is well-positioned to appeal to the widest array of parties. He also has Marine Le Pen’s blessing. She was reportedly in negotiations with Macron over the prime minister pick and gave her nod of approval to Barnier, who could plausibly pursue RN interests. With no real majority in parliament, any French government will require the tacit approval of both the center and Le Pen’s troops to stay afloat.

Within weeks of Barnier’s appointment, the left tabled a motion of no confidence in an attempt to topple the government. But, unsurprisingly, it raked in a measly 197 votes—presumably the NFP and a handful of centrist dissidents. With those few exceptions, Barnier retained the support of the centrist and conservative blocs. That was only 200 or so seats—not enough to save him. This left him in the uncomfortable position of having to flirt with the RN so that its 126 members didn’t join forces with the left. Though unpopular, his strategy evidently worked.

That said, Barnier is on thin ice. The government’s fate rests on the condition that he will keep Le Pen happy, or in other words, act as an RN pawn. She is poised to help Barnier survive, for now, but only insofar as he pursues policies that address her party’s populist and nationalist concerns.

After July’s fanfare around the NFP victory – and the supposed triumph of European liberalism – the present picture of France is rather bleak. The government is at the mercy of the far right, but not because that’s what France voted for. Macron’s decision justifiably alarmed the French left. In abandoning constitutional convention, he compromised the integrity of French democracy. However, neither Castets nor Mélenchon had sufficiently broad appeal. A far-left government would not have stood a chance in the face of a no-confidence vote. Macron knew it, Le Pen knew it, and the NFP ought to come to terms with this fact too.

This is not to say that the NFP’s agenda is outrageous or objectionable. The LFI and Mélenchon aside, the coalition’s policies are straight out of the social democracy handbook. They are not radical by any means and they are exactly what France needs to clean up the mess of Macron’s presidency. But NFP’s public image is one of extremism, not one of reasonable and level-headed reform. As long as Mélenchon’s left continues to frame itself as a force of havoc and division, the French will perceive it as such. For the sake of democracy, and itself, the French left must stop alienating France.

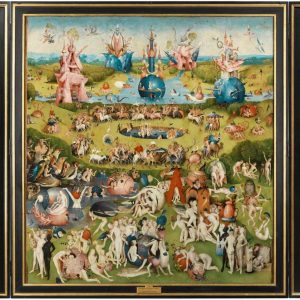

Featured Image Source: Le Monde

Comments are closed.