Less than two months before the presidential election, Nebraska lawmakers sprang into the national limelight as Republicans sought to change how the state awards its electoral votes. Unlike 48 other states, Nebraska does not award all of its electoral votes in the Electoral College—the body that ultimately elects the president—to the winner of the statewide popular vote in a “winner-take-all” system. Instead, it awards two electoral votes to the statewide winner and one electoral vote to the winner in each of the state’s congressional districts. With a competitive election against Vice President Kamala Harris, supporters of former President Donald Trump saw changing Nebraska to a “winner-take-all” system as giving an edge to the Republican ticket in the Electoral College. Republican Lindsey Graham, Senator of South Carolina, summed up the appeal in one sentence: “to my friends in Nebraska, that one electoral vote could be the difference between [Kamala] Harris being president and not, and she’s a disaster for Nebraska and the world.” For example, if Harris won the three Rust Belt states of Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin, but lost the Sun Belt states that Biden won in 2020, one electoral vote from Nebraska would decide if she wins or if the Electoral College ties. Although this effort ultimately failed after proponents did not secure a united Republican front in the Nebraska state legislature to overcome a Democratic filibuster, it provides insight into the politics of the Electoral College beyond just its implications in the final tally. Thus, splitting electoral votes by congressional district encourages competition outside of traditional swing states and increases representation, but is also prone to gerrymandering and extenuating polarization.

The practice of proportional electoral votes is not new, as both Maine and Nebraska—the only two states that have such a system—have done so for decades. Maine passed legislation in 1969, while Nebraska adopted the same process more recently, in 1991. Though the two states differed in their rationales for enacting such a system, both were done so to increase voter representation in electing presidents. Disparity in representation in the 1968 presidential election, featuring Republican Richard Nixon, Democrat Hubert Humphrey, and third-party candidate George Wallace, motivated the split in Maine’s electoral votes. In that election, Nixon won the national popular vote by just 0.7 percentage points, yet held a 110 electoral vote advantage over Humphrey (Wallace won 13.5 percent nationally, carrying 46 electoral votes as his support was concentrated in the South). In Maine, all of the state’s four electoral votes were awarded to Humphrey despite around a 12 point difference between him and Nixon. This stark discrepancy made the case for reform to account for an Electoral College that is more representative of voters for candidates with a minority of the statewide vote. Maine remained unique in its adoption of the reform case until Nebraska joined it in 1992. However, Nebraska legislators were convinced by another point: a desire for increased relevance in presidential politics. At the time of the proposal (and with the exclusion of Lyndon B. Johnson’s 1964 national landslide), Nebraska had voted for the Republican presidential candidate in 12 consecutive elections. Using the logic that presidential elections are often decided in a handful of swing states, it would be ineffective for a Democratic presidential campaign in a “winner-take-all” Nebraska as, statewide, is solidly in the Republican column. Democrat DiAnna Schimek, a Nebraska legislator, argued that moving away from awarding electoral votes solely to the statewide winner would increase Nebraska’s stature in the Electoral College math and bring candidates to engage the state. Schimek’s Republican colleagues agreed and the measure passed, albeit narrowly, joining Nebraska with Maine in this unique electoral rule.

Source: Lincoln Journal Star

Neither Maine nor Nebraska would see their electoral votes split until the 21st century, but these instances demonstrate the system’s relevance and impact in representation. In 2008, Democrat Barack Obama carried Nebraska’s 2nd congressional district, though Republican John McCain won Nebraska statewide and in the other two districts. The Obama campaign ran a significant operation to sway the 2nd district, with NBC News noting it had “three campaign offices in the district and had 16 paid staff during the campaign.” This presence would have been unlikely if Nebraska did not split its electoral votes, as the Obama campaign would not have been able to overcome the state’s overwhelming Republican lean. Democrat Joe Biden would again win the Omaha-centered district in 2020. Across the country, Republican Donald Trump won Maine’s aptly numbered rural 2nd congressional district in 2016 and 2020. In 2016, then-candidate Trump made five visits to the district that paid off as he siphoned an electoral vote from Democrat Hillary Clinton, who had won the rest of the state and the 1st district. Beyond increasing relevance for the minority party, the prospect of split electoral votes also engages the majority party. With Maine’s 2nd district’s voting history, the Harris campaign has opened 10 of its 17 Maine offices in the district. Under this system, Maine and Nebraska voters are in play: major party candidates campaign in districts less partisan than the rest of the states they are located in, paying attention rather than writing them off as insurmountable challenges. Political analysts agree, with University of Maine professor Mark Brewer telling Nebraska Public Media that “George W. Bush campaigned in Maine to try to grab a vote. Trump went out of his way to come to a site in Maine’s second congressional…and he wouldn’t have done that if there wasn’t a split electoral college vote.” Furthermore, voters for the losing candidate are still represented in the Electoral College tally rather than being ignored in the map of “red states” versus “blue states.” Brewer said this system allows a hypothetical voter living in a competitive congressional district to think “since it’s a split vote arrangement, then my vote can still matter.”

Splitting electoral votes by district is not without its challenges. With their small allocation of congressional districts and, by extension, electoral votes, Maine and Nebraska have not been battlegrounds for gerrymandering—the process of manipulating electoral boundaries for partisan gain. However, if every state adopted this system, it could easily morph into a new problem where the decennial redistricting process could be manipulated to win presidential elections (in addition to congressional elections). Barry Burden, an elections researcher at UW Madison, projected this drawback and pointed out that in 2012, Barack Obama won the national popular vote although Republican Mitt Romney won a majority of congressional districts. In 2020, Joe Biden became the first Democrat to win the state of Georgia since 1992, with a plurality of the statewide popular vote, but carried a minority—six of 14—of the state’s congressional districts. During redistricting after that year, the Georgia state legislature enacted a gerrymandered map to increase the GOP majority in its congressional delegation. It worked; Democrats lost a seat in the 2022 elections after Congresswoman Lucy McBath switched districts and defeated another incumbent since the map essentially ceded her seat to the GOP. Had Georgia followed in Maine and Nebraska’s footsteps by splitting its electoral votes, Biden would’ve been underrepresented in the Electoral College in 2020 and would’ve had an even harder time with later elections in 2020s. In a twist, a similar issue arises in states where one party routinely carries the state by small margins at the presidential level but the other party controls state government. This dynamic created support for splitting the state’s electoral votes by district amongst Republicans in Michigan, Pennsylvania, and Wisconsin—three states that, with the exception of 2016, fell into that categorization—with the rationale being that such splits would dilute a future winning Democrat’s advantage compared to the “winner-take-all” system. While none of the proposals were implemented, they were criticized for the imbalance that they would create. Regardless of which way this challenge is spun, the argument for states to split their electoral votes by district must also take into account that the process of drawing congressional districts is not necessarily fair.

Source: Travel + Leisure

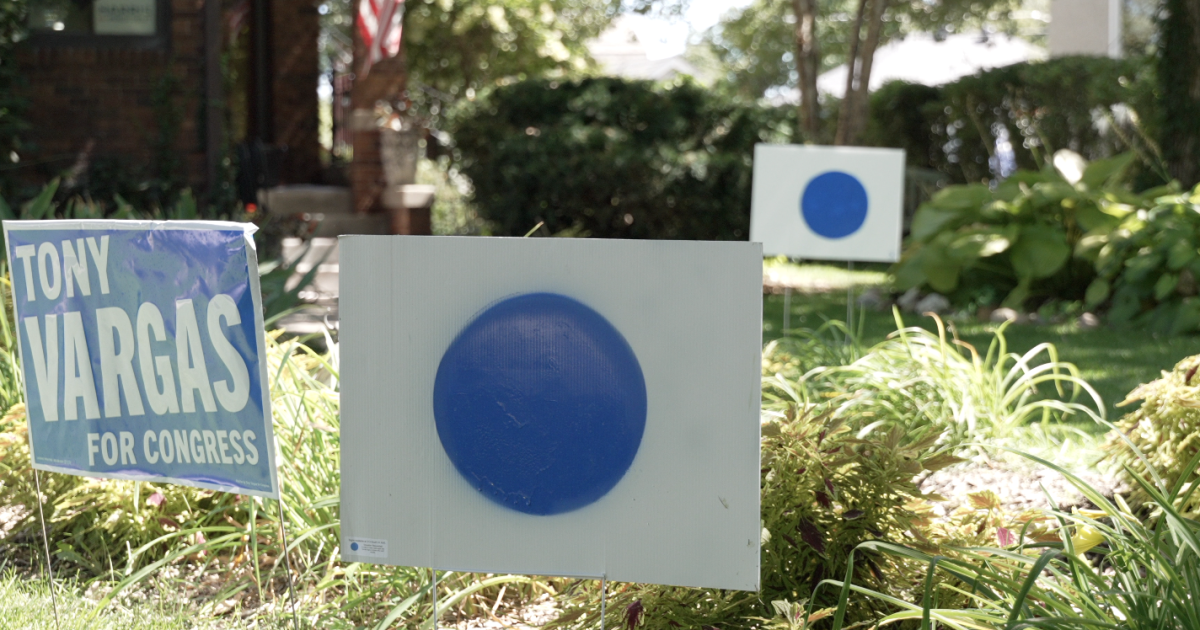

A second challenge to proportioning electoral votes by district raised by Stanford Professor Jonathan Rodden is the urban-rural divide. 2024 data from the Pew Research Center shows urban and rural counties are nearly mirror opposites in their partisan preferences (suburban counties, practically even, are the “battleground”). In Maine, the rural 2nd district voted for Trump twice although the more urbanized 1st district—encompassing the state’s most populous city of Portland—is more consistently Democratic. In Nebraska, the Omaha-centered 2nd district contrasts the state’s more rural 1st and 3rd districts. Supporters of Kamala Harris in the 2nd district have put up around 10,000 “blue dot” yard signs, symbolic of a “blue” island in Omaha within the “red” sea of Nebraska. This pattern repeats itself across the country, from Pennsylvania to Florida and Virginia to Nevada. Regardless of how the divide manifests itself, splitting electoral votes by district has the potential to enable increased responsiveness from presidential candidates. The issues affecting urban and rural voters are as different as they are similar. A rural voter might want to know a candidate’s agricultural policies, but an urban voter is likely more concerned with housing affordability. Rather than one carefully crafted speech designed to capture voters—many with different priorities—from an entire state, candidates can tailor their message as necessary.

The American electorate has become more and more negative. A component of this dissatisfaction relates to institutions, including the Electoral College, on which 63 percent of voters support replacing with a popular vote system. A first step towards restoring faith in democracy is making presidential elections more representative and relevant to the everyday American, no matter where they live. A state should not be written off as for one party or the other, nor should a voter be forgotten in a winner-take-all electoral vote count. Of the many proposals to improve American institutions, splitting a state’s electoral votes by congressional district has the potential to do just that, if coupled with other reforms to guarantee that it is a solution and not a Trojan horse in the making.

Featured Image: KMTV 3 News Now Omaha

Comments are closed.