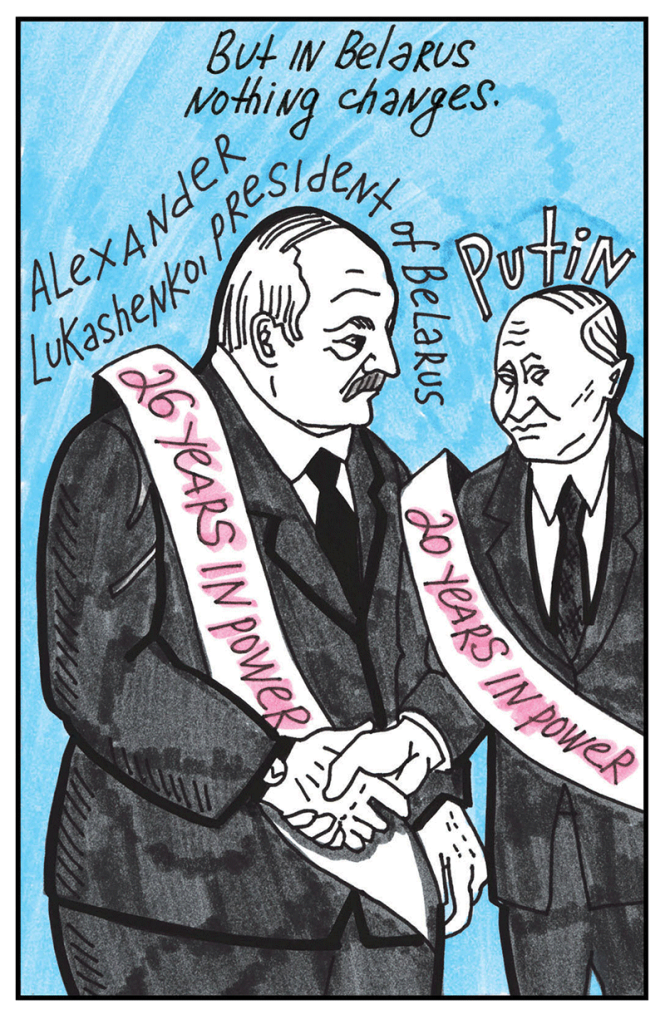

Ukraine fights for freedom, while Belarus clings to dictatorship. At the heart of both struggles lies the same force: Vladimir Putin’s relentless pursuit of control over post-Soviet states. Ukraine is not the only country fighting against Russian influence. Aleksandr Lukashenko, who embraces the title as Europe’s last dictator, was elected president of Belarus in 1994. His iron-fisted three decade rule has been met with frequent protests against predetermined election cycles. His ties to the Kremlin have turned the country into a mirror of the former USSR’s surveillance and political repressions.

Ukraine, a state that resisted Russian influence through protests with ambitions to join the EU and NATO, is at war with Russia largely because of its attempts to separate from Putin’s control. Belarus, a country that because of its cooperation with Moscow, has become one of the least democratic states in the world and a Russian vassal state. The state of these countries describe the danger behind Putin’s action as a threat not only to sovereignty, as in the case of Ukraine, but also as a threat to democracy.

Section One: Belarus—Russia’s Puppet State

Like many post-Soviet states, Belarus has struggled to break away from Russian influence. After Lukashenko’s election in 1994, he began to strengthen ties with Russia by joining the Kremlin’s Collective Security Treaty Organization to counter NATO. Belarus became economically dependent on Russia during Lukachenko’s reign of power. The dependance has transformed Belarus into a ‘puppet state’ in Russia’s orbit. For Russia, its influence in Belarus is necessary to Putin’s rebuilding of the Soviet Union and regaining the power the country once had.

The first major peaceful demonstration against Belarus’s puppet government was in 2010, when the country announced an eighty percent victory for Lukashenko. Government special operation forces and riot police responded violently, arbitrarily arresting anyone who challenged Lukashenko’s regime.

Over 600 protesters were arrested, along with five former presidential candidates who were thrown in jail under the pretense of inciting riots. In the elections of 2020, a government exit poll claimed Lukashenko won the election with nearly eighty percent of the vote. Thirty-five thousand protesters were arrested, and seven thousand were violently suppressed in police custody. Lukashenko labeled the protesters as “foreign puppets,” enemies to Belarus.

During the 2020 protests, Putin vowed to send his own forces into the country in order to fight what he called “violent extremism.” Belarusian elites were split in their support for Lukashenko. The opposing elites were perceived as a threat to Lukashenko. Putin donated a sum of 1.5 billion dollars to regain support for Lukashenko. Putin’s actions were representative of Moscow’s vested interest in sustaining autocratic regimes like Belarus, where Russian influence is easily maintained.

Belarus’s alignment with Russia represents the critical role that these post-Soviet states have in the Kremlin’s broader geopolitical strategy. During the war in Ukraine, Belarus allowed for Russian use of its airfields, and use of its shared border with Ukraine. The border gives Russia close proximity to Kiev, Ukraine’s capital. Belarus highlights how former Soviet states can either fall deeper under Russian control, or in the case of Ukraine, resist this control and fight for sovereignty.

Section Two: Ukraine—The Fight for Sovereignty

Ukraine’s Orange Revolution in 2004 marked a decisive rejection of Russian control by overturning the results of the fraudulent election of a Moscow-backed candidate. The nonpartisan Committee of Voters of Ukraine claimed the 2004 election was “the biggest election fraud in Ukraine’s history.” Over one million protested, leading to Ukraine’s supreme court declaring a runoff election overturning the fraudulent election results with Viktor Yushchenko winning the presidency.

Yuschenko ran with ambitions to join the EU and NATO, and typically aligned with ideologies pushed by the west. It was the start of Ukraine protesting against Russian influence, and for Putin, a threat to his interests in Ukraine ultimately leading to Russia’s aggressive responses.

The Orange revolution was a prelude to the 2014 demonstrations in Kiev’s giant square, dubbed “Euromaidan,” which generated a tidal wave of Ukrainian nationalism. Ukraine’s defiance demonstrates the dangers of rejecting the Kremlin’s control.

For Belarus, it is an opposite tale of a country that accepted Russian influence from its beginnings. Lukashenko’s autocratic rule relies entirely on Russian support, allowing him to suppress demonstrations. The country, according to Freedom House, is currently ranked in the bottom twenty-five percent across all categories of democracy, performing the worst amongst European countries. While Ukraine has fought to break free from Russian control, Belarus’s acceptance of Russian influence has entrenched autocracy.

Section Three: Belarusian Defiance

A key opposition leader, Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya, has led an oppositional Belarusian government since she was exiled in 2020 by operating from Lithuania and Poland. Lukashenko calls Sviatlana a puppet of the west, while she calls Lukashenko a puppet of Russia.

Since the founding of her oppositional party, Tsikhanouskaya has recruited volunteer fighters from Ukraine. She attended the 2024 United Nations General assembly to shed light on the autocratic government in Belarus and the war in Ukraine.

“No war, no fight can be won without allies,” she stated, referring to the United States as “a beacon of hope for many nations.”

Both Ukraine and Belarus demonstrate the importance of this war, not only to the country of Ukraine, but to all post-Soviet states. Tsikhanouskaya not only represents a challenge to Lukashenko’s regime, but also strikes at the heart of Putin’s strategy to prop up autocratic governments in post-Soviet states. Her fight symbolizes the broader struggle for democratic governance that Russia seeks to suppress across these former states of the USSR.

Section Four: The Spread of Russian Influence

Georgia is another country that has seen an increase in Russian influence ever since the 2008 Russo-Georgian war. The war was described by journalist Peter Dickinson as “Putin’s green light”. Russian forces fought against the Georgian military in South Ossetia, an autonomous republic in Georgia. It was a breach of Georgian sovereignty and the first major European aggression since World War Two. Since the war, the Georgian government has experienced Russian infringement on its politics through South Ossetia, which Russia effectively controls.

At the end of September, the Georgian parliament signed an anti-LGBTQ bill that bans public displays of the LGBT flag and censors LGBT representation in popular media. This bill mirrors Russia’s own anti-LGBTQ bill. The acceptance of the bill demonstrates how the Kremlin’s traditional and conservative values still hold a grip on the country. The bill distances the country from the pro-European stance it had previously undertaken with hopes of joining the EU. Georgia’s president Salome Zourabichvili, a supporter of Ukraine, is losing support in the country as it is becoming increasingly pro-Russian, with the majority Georgian Dream party supporting the bill.

The stories of Ukraine and Belarus give indications of the complexities of being a post-Soviet state in the 21st century. Citizens in these states strive to reject Russian influence, yet Putin has dominated state politics by supporting domestic autocratic groups like Lukashenko’s. Ukraine managed to break free from Putin’s grasp. Because of this, the country now faces a war within its borders. These two states depict the extreme realities of being a former Soviet state in the 21st century, and how thirty years later, the world is still recovering from the USSR’s collapse.

Featured Image Source: The Nib

Comments are closed.