The Prussian General Carl von Clausewitz famously said “War is merely the continuation of policy with other means.” A state sets a definable list of objectives, and when diplomatic or conventional political means do not suffice, it turns to military means to achieve its goal. War may be accompanied by violence, destruction, and chaos. However, it should not be aimless. This policy-centered paradigm can be applied to Israel’s current war efforts in Gaza, Lebanon, and potentially Iran.

On October 7th 2023, the Palestinian militant group Hamas launched an attack on Israel’s southern communities. Nearly 1200 people died and around 251 Israeli citizens were taken as hostages.

The day after, a closely connected conflict began on its northern border. The Lebanese military group Hezbollah, in a supposed act of solidarity with Hamas, began firing rockets at Israel’s towns. As a result, the Israeli Defence Forces (IDF) have been dually locked in a mass scale war in Gaza and simmering skirmishes with Hezbollah. In the south, the war has resulted in mass destruction and the death of more than forty thousand Gazans. In the north, fighting has internally displaced about sixty thousand Israelis fleeing the conflict.

Israel’s stated goals are to destroy Hamas, return the hostages, and neutralize Hezbollah in the north so that it can return its citizens to the north. However, all of these official policies are local and do not constitute Israel’s fundamental geopolitical aims. To understand Israel’s wider aims, one must recognize the thread that connects these separate policies together: Iran.

Since the Islamic Revolution of 1979, Iran has been uncompromisingly committed to Israel’s destruction. Its previous Supreme Leader Ruhollah Khomeini described Israel as the ‘little Satan’ to America’s ‘big Satan’ and made opposing Israel a central part of Iran’s political culture. Prior to the recent conflict, Iran has never directly struck Israel, opting to apply pressure through proxies like Hamas and Hezbollah. To use Clausewitz’ maxim, one might say that the supplying of military groups like Hezbollah and Hamas are the ‘other means’ by which Iran has continued this policy of Israel’s demise.

Hezbollah provides Iran with a threat to Israel from its northern border with Lebanon. Like Iran, Hezbollah follows a Shiite interpretation of Islam, aligning the two ideologically. This alignment goes all the way back to Hezbollah’s roots. In an attempt to exert power in Arab states, Iran supported Hezbollah’s formation in 1979, providing the necessary funding and training to get the organization operational. Hezbollah made its alliance with Iran a part of its manifesto and over the years, Iran has supplied Hezbollah with tens of thousands of rockets and weaponry to maintain a constant threat against Israel.

Hamas, by contrast, is a Sunni group. Therefore, there is an ideological distance between Hamas and Iran that does not exist between Hezbollah and Iran. When Hamas refused to join Hezbollah in giving unconditional support to Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad’s campaign against Sunni insurgents, this caused a rift between Hamas and Iran. However, Hamas is still close to Iran and depends on its support. As a Palestinian group, Iran is interested in supporting Hamas as part of its anti-Zionist policy, providing Hamas with tens of millions of dollars in annual funding. Furthermore, during Hamas’ current war with Israel, Iran has activated its proxies Hezbollah and the Houthis in different fronts to help divide Israel’s attention across the region.

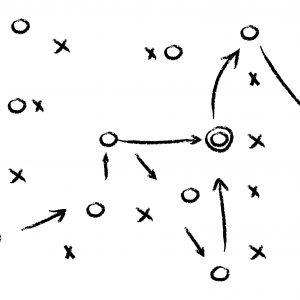

Former Israeli Prime Minister Naftali Bennett, describes Iran as the “octopus’s head” and Hamas/Hezbollah as the “tentacles.” This policy of supporting Hamas and Hezbollah has been described as ‘asymmetric warfare’ as Iran inflicts damage on Israel without having to directly confront Israel on the battlefield. The ultimate end of Iran’s policy is to erode and exhaust Israel to the point of self-combustion.

Flipping this equation partly explains the current wars that Israel is fighting. One may view Israel’s current war objectives, aimed at the “tentacles” of Hamas and Hezbollah, as the columns upon which a broader, more fundamental counter-Iranian policy is being pursued. To frame this in Clausewitzian terms, Israel views its wars against Hezbollah and Hamas as the continuation of an anti-Iran policy with other means. In this picture, defeating Iran and its proxies represents Israel’s chance to ensure its geopolitical security and put an end to constant war.

Recent events suggest that this tense struggle between Israel and Iran has begun to shift in Israel’s favor. In the past year, Israel dismantled most of Hamas’s fighting forces. Over a two week blitzkrieg of special operations that started on September 17th, Israeli intelligence and the IDF decimated Hezbollah’s senior leadership, along with its leader Hassan Nazrallah. Most importantly, Israel depleted a large amount of Hezbollah’s 120,000-200,000 Iranian supplied ballistic missiles and rockets. This was a tactical necessity as Hezbollah’s arsenal of heavy weaponry formed the bulk of Iran’s defense network against Israel. On October 1st, Iran tried to check Israel’s momentum with a foiled and largely ineffective missile attack, but only furthered the cycle of escalation. Collectively, these developments delineate the rapidly accelerating trend of the current war.

Having imbalanced Iran, Israel’s Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu now openly discusses delivering the knockout blow. He has warned Iran that regime change will come “a lot sooner than people think,” suggesting retaliations could topple the existing Islamic Republic. These potential retaliations include the possibility of destroying Iran’s nuclear facilities or its oil infrastructure.

Arguably, the escalation of the conflict along this line constitutes a symmetrising of the Israel-Iran rivalry. After years of “equilibriums” in which Iran deterred Israel through its “tentacles,” Israel is scaling the means of its war to the scope of its anti-Iran policy. If, as suggested, this is a case of Israel tailoring its particular military effort to its wider geopolitical effort, then Clausewitz’s maxim provides a framework for evaluating the success of Israel’s war. These wars can be deemed successful if in neutering Iran, Israel finally achieves the ultimate aim of long-term security.

These recent developments clearly favor Israel and count as major tactical defeats for Iran’s wider strategy. However, arguably, the expansion of the war is inherently limited in its capacity to bring security for Israel. This is because if Israel views Iran as the only or main factor of Israel’s insecurity, it is viewing the picture with one eye shut.

Parallel to the complex web of war Israel is currently engaged in, there is a genuine political problem which bullets and bombs cannot solve. The fundamental political problem Israel faces is not an adversary, albeit a well armed one, that is situated more than 1,000 miles away. Rather, the invariant source of Israel’s insecurity is closer to home. It is the lack of an answer to the Palestinian question which is the genesis of these ceaseless cycles of conflict. If Israel cannot pair its tactical victories against Iran with genuine diplomatic developments with the Palestinians, it is unclear how this would be the last wave of war.

In the 1993 Oslo Accords, Israel and the Palestinian Liberation Organization, on behalf of the Palestinian people, mutually recognised each other and initiated a path to a two-state solution. However, since then, Israel has continued the expansion of its settlements in the West Bank. It has grown its political presence in the West Bank whilst purporting to be in favor of a two state solution. The military infrastructure put into place for the safety of Israeli settlers in the West Bank brought a complex network of checkpoints that make daily life increasingly unbearable for Palestinians.

Officially, this is under the guise of a “temporary” military occupation. However, Israel refuses to say under what conditions it would cease the occupation, making the claim that this is a temporary configuration implausible. The status quo is beyond unacceptable for Palestinians.

Even though the political situation is dire, the evidence suggests it is worsening with a new class of extremist far-right politicians in government. Finance minister Bezalel Smotrich called for “sterile security areas” that would ban Arabs from entering areas of the West Bank. National Security minister Itamar Ben-Gvir has emboldened violent settlers in the West Bank by arming them with more than ten thousand assault rifles. These are just two examples of how far-right hardliners increasingly assert their control over policy in the West Bank.

The effect of this widening political control over the West Bank is that the line between civilian and military government is blurring beyond recognition. Such a policy suggests that Israel aims to achieve a de facto one state solution where non-Israeli Arabs are treated as second-class citizens. In the name of security, Palestinians are subject to the rule of an Israeli occupation that severely limits their movements and leaves them vulnerable to settler violence.

The tension and fury this occupation produces is not a recipe for peace, but a precedent for more bloodshed. In fact, one could argue that this unjust situation in the West Bank, in addition to the brutal war in Gaza, merely ensures the ideological survival of Hamas and other militant extremist groups. If Israel really wants to permanently neutralize Iran’s proxy tactics, it must also consider its role in the cycle of hatred that sustains such militant groups.

Clausewitz’ maxim suggested that war is the means by which a policy is achieved. But, for too long, Israel’s policy has not corresponded to its political reality: Iran and its proxies are not the only players in this conflict. If Israel wants to achieve lasting security, it must end its policies’ sinister silence on the most important question it faces: how will we make peace with the Palestinians?

Featured Image: REUTERS/Fadi Amun

Comments are closed.