On the 24th of this July, Brayden McLean, outfitted in a hospital visitor sticker on his shirt, stepped away from his newborn triplets to ask the Berkeley City Council, “where will [my childrens’] generation be able to live and thrive in Berkeley?”

While largely considered to be a progressive city, Berkeley has become an epicenter of NIMBY-ism. Homeowners in wealthy neighborhoods have continuously blocked the development of new multi-family units. Organizations such as Save Berkeley’s Neighborhoods have even taken to litigation as a means of blocking development. Yet, the City of Berkeley is required to add 9,000 units by 2031, raising the question of where these units will be built and what they will look like.

Today, large developments face little to no opposition in dense, diverse areas such as Downtown Berkeley and West Berkeley. For example, the Zoning Adjustments Board recently approved a 27-story apartment structure in Downtown without a single comment in opposition. However, the city remains divided on middle-density development in traditionally single-family neighborhoods. In recent years, housing advocates have proposed “Missing Middle Housing” as a way to increase density in traditionally single-family neighborhoods. Missing middle housing can be duplexes, fourplexes, cottage courts, and courtyard buildings which allow for increased density at a lower cost to residents while also maintaining a small profile to onlookers as well to preserve the charm and character of neighborhoods. Proponents have pointed to affordability, availability, walkability, decreased reliance on cars, environmental sustainability, and community as benefits of missing middle density.

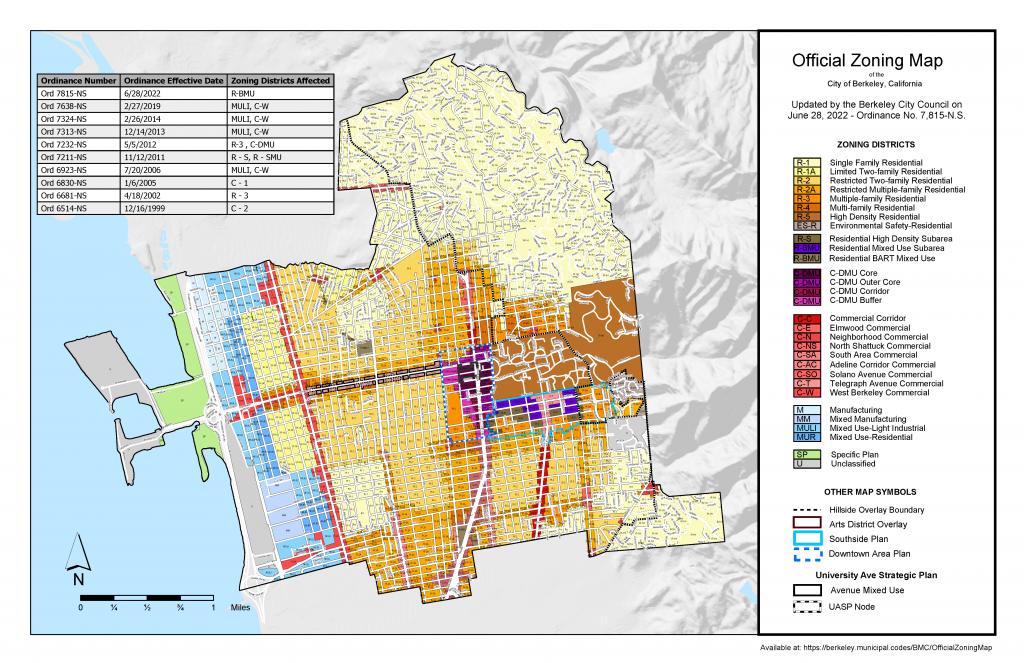

After a 2019 City Council referral to the Berkeley Planning and Development Department, the much awaited proposal on missing middle came before the council this past July. The department, which designs and implements housing and zoning law, presented the middle housing ordinance. Under this proposal, revised zoning laws would eliminate single-family zoning and allow for greater density by increasing maximums for lot coverage, building heights, and floor area ratio while decreasing requirements for building setbacks. In addition to the standard arguments in favor of missing middle came one specific to Berkeley: reversing the city’s legacy of racist zoning practices.

Berkeley’s exclusionary and divided housing was not a matter of chance. In the early 1900’s, the city pioneered single-family zoning as a response to housing developers’ concerns of Black families and an African American-owned dancehall moving in next to their high-end developments. City planners correctly assumed that by forcing every home to be a single unit on high-value properties, poorer residents, particularly Black people, would be priced out of the neighborhood. Thus, the “R1” single-family zoning was founded and propagated across the United States.

As our nationwide housing crisis worsens, we remain trapped by this early 20th century policy. Today, 75% of residential land in America is zoned exclusively for single-family homes. Within California, UC Berkeley’s Othering and Belonging Institute found that over 95% of total residential land area is zoned as single-family-only. The socioeconomic ramifications are apparent: less wealthy families are edged out of communities, struggle to find affordable housing, and are forced to live in neighborhoods with worse school districts, fewer economic opportunities, and overall less economic mobility. Furthermore, R1 zoning continues to create modern-day racial segregation. The same UC Berkeley study found that California cities with above 96% single-family-only zoning are nearly 55% White, despite the state being only 35% White.

In Berkeley, restrictive zoning laws remain ever prevalent. Neighborhoods such as the Berkeley Hills, Thousand Oaks, and Elmwood are mostly single-family zoned. While the rest of Berkeley is mostly zoned as R2 (two-family residential), zoning laws maintain strict density, lot coverage, and floor-area ratio requirements suppressing overall housing availability. Cecilia Lunaparra, a progressive, pro-development City Councilmember, stated in the July council meeting, “[our current zoning law] is actively displacing residents. We are artificially increasing the cost of homes across the city.”

Not only are zoning policies decreasing the affordability of Berkeley homes, we still see the vast racial disparities by neighborhood. In the Thousand Oaks, Berkeley Hills, and Elmwood neighborhoods, white residents represent over 62% of the population, while Hispanic and Black residents are largely condensed to the higher-density areas of West Berkeley. Following bans on new multi-family developments in the 1960s, Berkeley’s Black population has dropped by 70% since 1970. The only neighborhoods where the Black population and overall diversity have grown are neighborhoods in which new units are being built (Downtown and the waterfront). Meanwhile the Black population has fallen every decade in neighborhoods where development has stopped.

With the missing middle housing ordinance, Berkeley has the chance to live up to our claims of equity. It would help middle-class residents to find housing in their price range within any neighborhood, increase the supply of housing, and dismantle the laws that have segregated our neighborhoods.

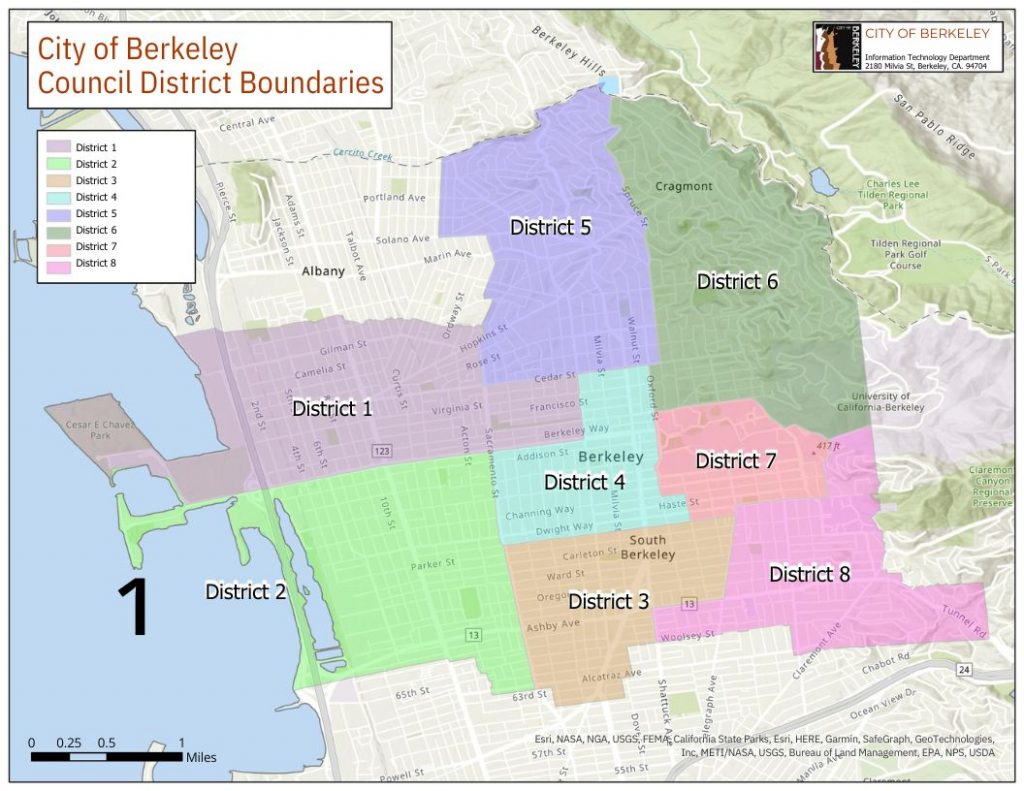

The July 24th special meeting was filled with advocates, like Brayden McLean, supporting a more inclusive and affordable Berkeley. Countless residents expressed their frustration with the housing markets and concerns with their ability to afford living in Berkeley. Councilmembers Cecilia Lunaparra, Mark Humbert, Rashi Kesarwani, Ben Bartlett, Terry Taplin, and Igor Tregub expressed broad support for approving middle housing. Meanwhile, Councilmembers Susan Wengraf and Sophie Hahn, who represent the Berkeley Hills and Thousand Oaks respectively, expressed greater reluctance to support these policies.

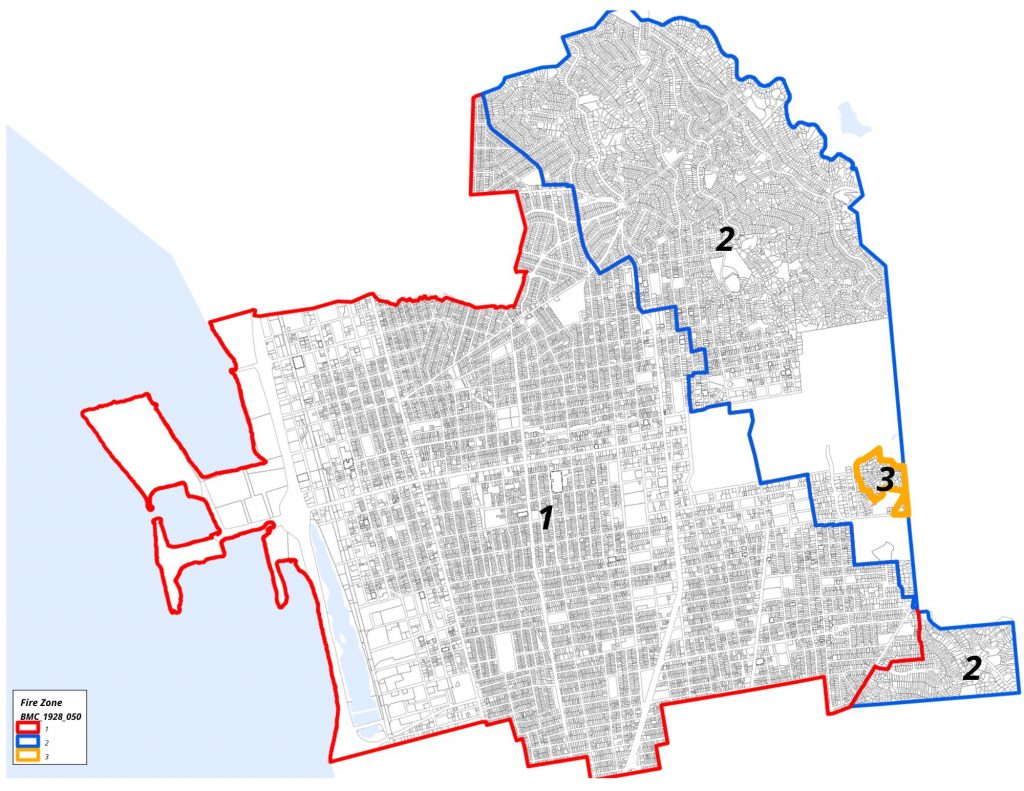

The largest concern that opponents, including the two council members, expressed was fire dangers in the hills. In the days prior to the meeting, the Fire Chief sent a memo to the council detailing risks in the “hillside overlay”, which includes the overwhelming majority of the districts Wengraf and Hahn represent. Citing historical fires (including the deadly 1991 fires), evacuation difficulties, weather, small building separation, and fire department staffing difficulties, the Fire Chief warned against increasing population density in the overlay. Residents came with anecdotes of narrow, windy streets, filled with parked cars, creating evacuation risks.

Wengraf, whose legacy on city council boasts numerous fire risk mitigation and fire education efforts, told me in an interview, “It’s just a reality that the population density exceeds the capacity of our roadways.” She pointed to a lack of public transportation, and consequent car dependence, in conjunction with no current requirements for off-street parking as dangers for the hills. Wengraf continued, “The infrastructure does not have the capacity to carry the number of people who live in the hills to safety in the event of a wildfire.”

Yet, as many members of the public along with Lunaparra and Kesarwani pointed out, much of the hillside overlay (such as the Northside neighborhood, the west of Wengraf’s district, and much of Hahn’s district) lies in areas with access to public transportation that are largely not steep, close to main roads, and comprised of straight, relatively wide roads. Those are amongst the wealthiest neighborhoods in Berkeley.

One Berkeley Hills resident commented, “I have a lot of concern about [Wengraf’s] real concern of fire, [however] council cannot simply use fire as a method to prevent housing in the most wealthy and exclusionary zones of the city.”

Furthermore, many residents argued that the danger of upzoning could be mitigated by clearing fire-prone vegetation, such as the invasive eucalyptus. It was also noted that, as of 2008, new developments in the hills are required to be built with fire resistant standards, which the majority of current homes are not.

Most of the council expressed a support for excluding the hills overlay until the release of the Fire Evacuation Study — a scientific study of fire risk and fire harm mitigation, which Wengraf stated would not be ready until January. Regardless of the results of the study, Wengraf and Hahn seemingly remain firmly against increasing density in any portion of the hills. “If we’re talking about building affordable housing, this is not the place to build,” Wengraf told me in my interview with her.

Another key divide in the council is on the maximum density of units on a lot. The Planning and Development Department put forth a plan without any maximum. Hahn, who ran for mayor in 2024 and has expressed support for missing middle in the past, said in her newsletter, “I still strongly support Missing Middle housing, but the Planning Commission’s proposal… once again swings the pendulum too far in the opposite direction.” She continues, “In the name of ‘simplicity,’ the Planning Commission imposes a uniform set of standards in all residential neighborhoods that will allow double, triple, or even larger multiples of ‘four units’ on most residential parcels.”

One must ask why a density maximum would be of concern (maybe given the exception of the hills). Given the building’s physical volume and property coverage are capped under the ordinance, and safety regulations are still in effect, maximizing the number of people that can live in a property should be self-evident.

Lunaparra motioned to proceed with the Planning Commission’s rezoning recommendations, given a hillside overlay exemption until the Fire Evacuation Study with support of Bartlett and Taplin. However the motion failed as she was voted against by Wengraf and Hahn, and the rest of council abstained.

Instead, council asked Planning and Development staff to modify the ordinance to add caps on unit density based on the prior R1, R-1A, R2, R2-A, and MU-R distinctions. Going forward, the City’s Planning department will research the considerations of the City Council, and a final vote should take place early next year.

When the goal of middle housing was to create across-the-board equity in all neighborhoods, it seems contradictory to set density caps along the previous distinctions. Bartlett, who represents South Berkeley, a neighborhood that has been successfully increasing its housing supply, questioned the exemptions for certain neighborhoods and the differentiation of density caps. “I’m wondering what we’re doing here,” he asks, “What we’re doing here today is just maintaining that status quo and exempting the very resourced neighborhoods from integrating.” He points out that his district, along with others, have been “fulfilling our duty to the future.”

Hahn and Wengraf also nitpicked smaller concerns on the ordinance. Hahn emphasized the confusing nature of zoning codes and their jargon (“who can raise their hand and tell me what FAR is?”), despite later raising qualms about the “ZAB.” Wengraf asked how people will charge their electric cars given no parking spaces. She went on to question whether this will even create housing affordability, but, as Lunaparra points out, the objective of middle housing is not to create affordable housing but integration and availability.

The community further harped on ideas of big, evil developers destroying single-family homes for large, profit-machining apartment complexes, despite the ordinance’s restrictions on the scale of these projects. The public revolted at the lack of communication with community members to be aware of the meeting and objected to the proposed removal of the public hearing process for new developments — both of which are typically attended by older, established residents who do not have other obligations in the middle of a weekday.

Amongst these objections, from minor and niche to stubborn and absolute, is a devoted rejection of financially accessible housing developments next to valuable single-family homes. The Berkeley community is unphased by a 27-story building in Downtown, yet thoroughly concerned and divided over what is supposed to be the Goldilocks solution to housing.

This is not to discredit those who are hesitant. The skepticism of big developers is understandable considering the mass of the ordinance. The concerns of fire in the hills are very real, however utilized as an absolute excuse without thought to the nuances many brought up. While ubiquitously in support of housing accessibility, those opposed fail to address in their remarks a central dilemma: how can we make our city more accessible if many neighborhoods are still treated as sanctified? While some objections stem from a place of genuine concern, most, whether knowingly or not, are preserving a legacy of socioeconomic and racial divide. Others, knowingly, appear to want to dictate what their neighbor’s house type (and consequently, their neighbor) looks like.

It seems Berkeley council members can write op-eds in favor of middle-housing and vote unanimously in favor of middle-housing research. Berkeley’s citizens can plant “all are welcome here” yard signs, label themselves as devout progressives, and want to solve the housing problem. But when it comes to action that will integrate our cities, we continue to exclude the dancehall.

Featured Image Source: Beth LaBerge/KQED

Comments are closed.