The day after Donald Trump was convicted on 34 felony charges, his campaign raked in a staggering $52.8 million in donations. Let that sink in. A former president became a convicted felon, and within 24 hours, millions of Americans opened their wallets to help put him back in the White House.

Fifty years ago, this would have been unthinkable. In 1973, Vice President Spiro Agnew resigned in disgrace over allegations of financial misconduct and tax evasion. Not convictions, not an arraignment, mere allegations. The weight of a scandal was enough to force him out of office. Today? A conviction isn’t a career-ender, it’s a fundraising bonanza.

Scandals once destroyed political careers. Now, they fuel them. How did this happen, and what does it mean for modern politics?

The Clinton Precedent

The death of the political scandal can be traced back to 1995, when a 22-year-old Monica Lewinsky first met then-President Bill Clinton. What began as a private affair would explode into one of the most infamous political scandals in American history, but the road to Clinton’s impeachment wasn’t a straight one. The scandal emerged from a broader investigation led by independent counsel Kenneth Starr. His investigation originally focused on the Whitewater controversy, a failed real estate investment involving the Clintons. But with no clear evidence of wrongdoing in Whitewater, Starr’s investigation expanded its scope, eventually uncovering Clinton’s affair with Lewinsky and his alleged attempts to cover it up. By 1998, Clinton faced perjury and obstruction of justice charges for lying under oath about his relationship with Lewinsky, culminating in his impeachment. And yet, Clinton’s public ratings soared. The Senate eventually acquitted him and he completed his term in office. He had weathered arguably the biggest political scandal in American history—and emerged all the better for it.

Clinton’s survival was a masterclass in political maneuvering. From the outset, his administration recast the scandal as a partisan hit job. Starr, once seen as an impartial investigator, was portrayed as a Republican operative obsessed with bringing Clinton down. The White House tied his investigation to previous efforts by conservatives to discredit Clinton and hence framed the impeachment as the culmination of a longstanding Republican vendetta. By shifting the conversation away from Clinton’s actions and toward the motivations of his accusers, Democrats turned the scandal into a political fight—one that could be won.

This shift would fundamentally alter how politicians approached scandals, setting a precedent that stands to this day. Clinton’s ability to survive impeachment proved that scandals were no longer as fatal as they once were. As long as a politician could keep their party loyal and reframe the controversy as a political attack, they had a fighting chance. In the coming decades, figures like Donald Trump, Brett Kavanaugh, and Andrew Cuomo would adopt similar strategies: doubling down, attacking their accusers, and weaponizing partisanship to insulate themselves from consequences. The old rules of political accountability were dead, and in their place emerged a new era where scandals became battles to be fought, not sins to be atoned for.

Guilt is for Losers

Accompanying the Clinton precedent was a critical realization: apologizing, resigning, or showing shame is often the worst strategy a politician can follow. Few figures embody this lesson better than Donald Trump. When the Access Hollywood tape—a recording of Trump boasting about sexually assaulting women—resurfaced in 2016, the scandal seemed poised to derail his campaign. Yet rather than apologize or express remorse, Trump dismissed the comments as “locker room banter” and immediately deflected, shifting the focus to Bill Clinton’s past sexual misconduct. He even claimed, “[Clinton] has said far worse to me on the golf course.” A similar pattern emerged during Trump’s first impeachment in 2019. Rather than deny that he had pressured Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky to investigate Joe Biden, Trump asserted that he had done nothing wrong and cast the inquiry as a politically motivated “witch hunt.” He claimed Democrats were attempting to stage a coup, “nullify the ballots” of millions of Americans, and overturn the 2016 election. The strategy was clearly the same one pursued by Clinton and his campaign. The playbook written during the Clinton impeachment had become a core survival mechanism in American politics.

This approach doesn’t just protect politicians from consequences—it also compels their party to rally behind them. When a political figure refuses to back down, their allies are left with two choices: either fully defend them or hand the opposition a victory. Brett Kavanaugh’s 2018 Supreme Court confirmation battle demonstrates this perfectly. Faced with sexual assault allegations, Kavanaugh did not attempt to project humility or suggest that he had made past mistakes. Instead, he delivered an indignant, combative defense while portraying himself as the victim of a Democratic smear campaign. His anger turned what could have been a politically costly scandal into a loyalty test by rallying Republican support. His indignation left Republicans a choice only between backing him, or complete loss—and most picked the easier option. Kavanaugh’s confirmation was ultimately secured, which proved that a defiant stance forces allies to choose between total loyalty or political defeat.

Breaking News: Nobody Cares

Compounding politicians’ strategies to weaponize scandals is the 24-hour news cycle and the relentless churn of social media. Scandals no longer linger; they are quickly overtaken by the next breaking story. This means that for many politicians, the best response to a scandal is to simply wait it out. Virginia Governor Ralph Northam exemplified this in 2019 when a yearbook photo of him in blackface surfaced. Amid the immediate outrage, many—including leaders within his party—demanded his resignation. But instead of stepping down, Northam refused to engage in the cycle of self-destruction. He denied he was in the photo (after initially admitting it), ignored calls for his departure, and eventually, the media’s attention moved on. Northam quietly finished his term in office, and if you Google his name today, the scandal doesn’t even show up. The moral of the story? Scandals have an expiration date, and politicians who can weather the initial storm will often emerge unscathed.

But the problem runs deeper than the speed of the news cycle. Constant outrage has numbed the public to scandal, replacing actual accountability with an illusion of it (constant outrage). Studies have shown that constant coverage of political issues can exhaust audiences and make them less likely to engage in pushback. This phenomenon was on full display during Trump’s first presidency, where an unending stream of scandals—from the Russia investigation to impeachment to classified document mishandling—created an environment where no single controversy could break through. The flood of accusations diluted their individual impact, allowing Trump to dismiss them more easily and his supporters to tune them out entirely.

What now?

The death of the political scandal isn’t just a shift in how we process wrongdoing—it’s a fundamental change in how power operates. When scandals no longer have consequences, corruption is no longer a risk—it’s a strategy. Politicians who once feared exposure now see it as a temporary inconvenience, knowing that time, partisanship, and media saturation will eventually dull any outrage. This creates a system where accountability is not just weakened—it is optional. And in a democracy, when consequences become optional, so does legitimacy.

If scandal no longer serves as a check on power, what replaces it? The answer cannot be outrage alone, because outrage, as we’ve seen, is easily absorbed and weaponized. What’s needed is something more sustained: political engagement that outlasts the news cycle, a public that refuses to forget, and institutions that enforce accountability rather than avoid it.

Politicians killed scandal, but its death is on us.

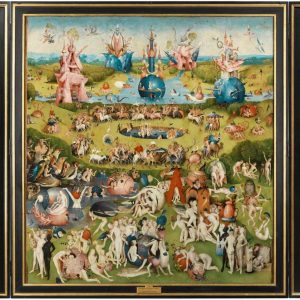

Featured Image Source: Britannica

Comments are closed.