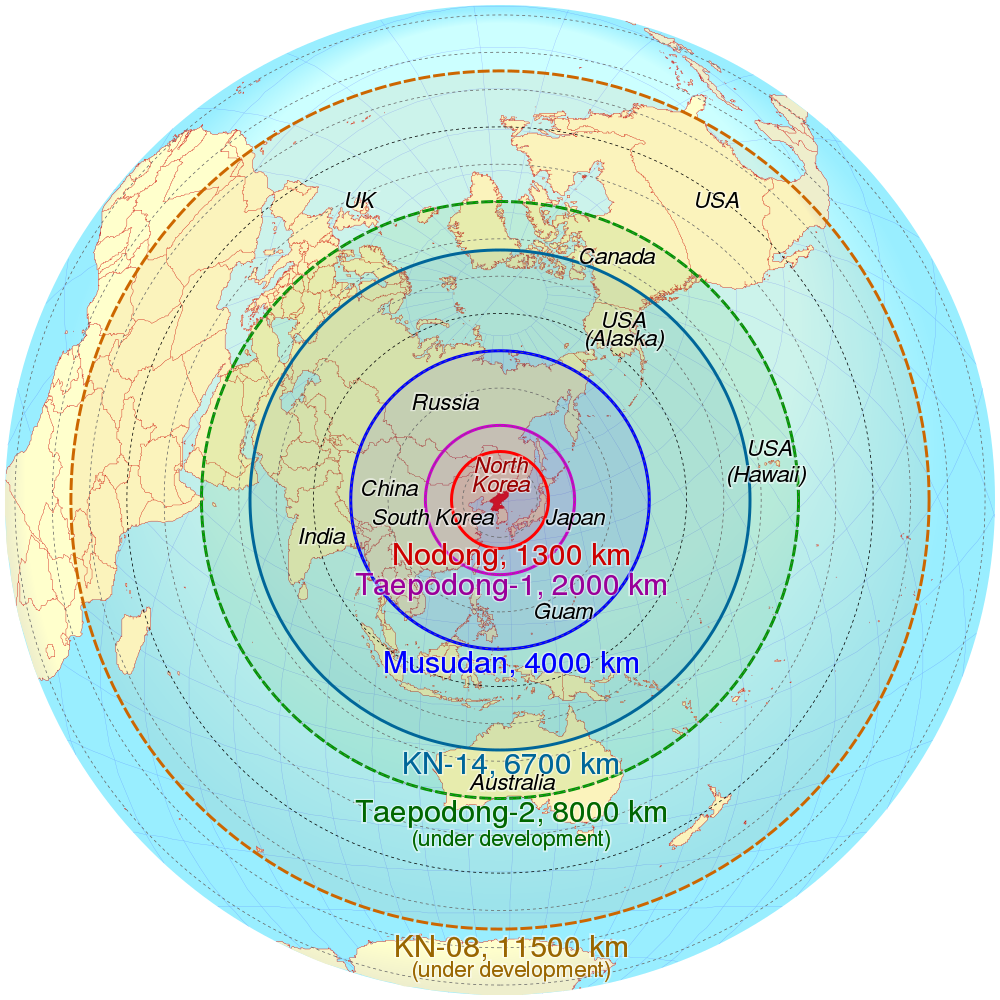

North Korea started examining a plan to target Guam — one of the the U.S.’s five territories — after Aug. 8th when President Donald Trump promised that “fire and fury” would befall the regime if they were to make any aggressions towards the U.S. or its allies. The tension has only escalated from there.

These events have put Guam squarely in the spotlight of U.S. media and politics, but in the background Guam has been making its own move, a move toward self-determination. While Washington scrambled to secure key military outposts in Guam against the North Korean threat, the Guamanian government’s Commission on Decolonization went to the U.N. on Oct. 3 to press the U.S. to decolonize their island.

To understand Guam’s drive for self-determination, it’s important to look at their history.

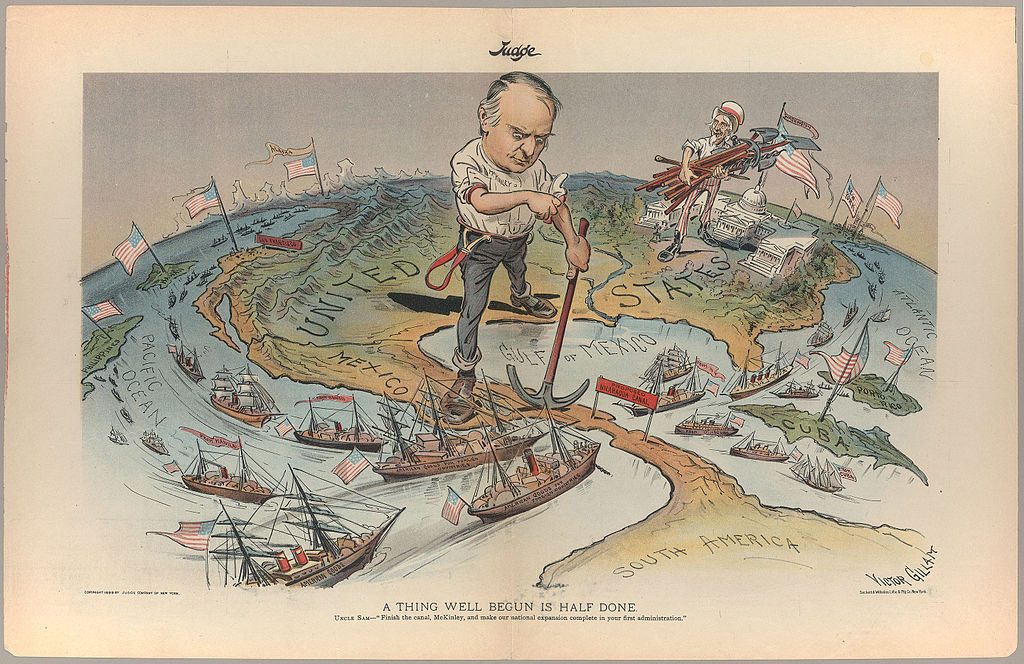

For thousands of years the island of Guam has been inhabited by the Chamorro people. Located in the Pacific Ocean as a part of a series of small islands, the Chamorro people were expert mariners and fishers. Then, in 1521, Ferdinand Magellan and his crew came across the island, and so began 300 years of Spanish dominance and Chamorro deaths. This history is unfortunately shared with many other indigenous peoples. It wasn’t until 1889 when the Spanish relinquished control of Guam after the Spanish-American War that the island fell to the the winning side: the United States of America. After that, Guam became an official U.S. territory.

Once again the Chamorro people were stuck under the thumb of an outside power. Life under the U.S. was not much better than with the Spanish. After the Spanish left, the Chamorros attempted to establish a democracy, but were instead put under the absolute control of the Secretary of the Navy. The island continued to be ruled by a succession of military governors, all of them treating Guam like a fortress instead of somewhere that people lived.

Chamorros and other Guamanians eventually received U.S. citizenship with the Guam Organic Act of 1950 along with rights to a local democracy. Their fight for this, however, was flaked with comments such as this one from the 1940s: “these people have not yet reached a state of development commensurate with the personal independence, obligations, and responsibilities of United States citizenship” from the U.S. Navy. The U.S. Navy even cited the “racial problems” of Guam, likely referring to the issue giving an indigenous-majority area democracy within a white-majority country.

The U.S.’ authoritarian control of Guam for this period of time closely follows the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s definition of colonialism: “is a practice of domination, which involves the subjugation of one people to another”.

But today, even as North Korea threatens Guam’s existence, the U.S. remains a continued threat to Guam’s sovereignty.

While Guamanians were given U.S. citizenship, they are still, in many ways, living within a colony. This act established the government of Guam, which includes the executive branch under the governor, a legislative congress, and a system of courts. In this sense, Guam’s government is very similar to that of a state. However, Guamanians only have a single, non-voting representative in the U.S. Congress and are not able to vote in the presidential general election while living on Guam.

Despite not being represented in the federal government, Guam is under the law of the federal government. This fact was enshrined in the case of Puerto Rico v. Sanchez Valle by which the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that Puerto Rico and other territories, such as Guam, were under Congressional and Constitutional laws. The Supreme Court is right — current law does not allow sovereignty for Guam and other territories. Their interpretation is sound. It’s the law that is not.

As to why Guamanians don’t get a vote for president, this is the U.S. Electoral College’s answer on their Frequently Asked Questions page: “No, the Electoral College system does not provide for residents of U.S. Territories (Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Northern Mariana Islands, American Samoa, and the U.S. Minor Outlying Islands) to vote for president. Unless citizens in U.S. Territories have official residency (domicile) in a U.S. State or the District of Columbia (and vote by absentee ballot or travel to their State to vote), they cannot vote in the presidential election.”

Basically, Guamanians don’t get a vote, because they don’t. There is no particular rhyme nor reason for it.

Despite lacking adequate representation or a right to sovereignty, Guam houses one of the largest and most strategic U.S. military bases in the world. Guam is a key part of the U.S. presence in the Pacific. It’s the farthest reaching piece of U.S. land into the area, allowing the U.S. to speedily come to the aid of Pacific allies (like Japan) and attack Pacific aggressors/enemies (like North Korea). The island is home to Navy ships, military bombers, and over 7,000 military personnel. A third of the land is controlled by the U.S. military.

The U.S. military has a history of misusing and polluting Guamanian land. Over the years they have disposed of materials such as nuclear and chemical weapons, cleaning compounds hazardous to humans and the environment, and insecticides and pesticides now banned as being carcinogenic or too dangerous. 20 percent of the land that the government owns has been designated as a “wildlife refuge” yet the federal government has put no money into protecting endangered species in the area.

For all the reasons listed above, the government of Guam created the Commission on Decolonization in 1997. Since its creation the commission has used its power to educate Guamanians about their colonial history and present and to petition the U.S. and the international community at large for self-determination. It is important to note that their official goal is not independence. While many Guamanians want independence, such as notable activist Victoria-Lola Leon Guerrero, others, like the Governor Eddie Calvo, are vying for statehood. Both parties, however, agree that Guam’s status as a territory must end.

The Guamanian government has attempted to hold plebiscites on the issue, but such attempts have been fraught at every turn. In the early 2000s it was constantly rescheduled in order to coordinate it with different elections and was ultimately cancelled due to low voter registration for the plebiscite. While Governor Calvo said the plebiscite was his top priority when he was elected in 2011, there has yet to be a vote. Guam’s government was also obstructed by a ruling in the U.S. 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, Davis v Guam, in which Arnold Davis sued Guam for restricting registration on the plebiscite to Guamanians who became U.S. citizens with the enactment of the Organic Act of 1950. Davis won the case on the basis of voter discrimination.

It is true that all Americans have a right to vote. It is true that although Davis is not a native inhabitant, he has made Guam his home and, according to the Constitution, has a certain right to determine what happens in the place where he lives. It is also true that Guamanians don’t get a vote in a country that they live, that the Chamorro people did not get to decide whether they wanted to be part of the U.S., and that they have faced decades of colonial exploitation and should, thus, be allowed to determine what they want to happen to their native land. Putting this argument aside: a plebiscite still needs to happen and Guamanians still deserve the right to self-determination.

So in October of 2017, Governor Calvo sent a delegation made up of both statehood and independence advocates to the U.N. in the hopes of curbing U.S. presence and influence over Guam. The delegation came before the Committee of 24 or, as it’s also called, the Special Committee on Decolonization. The committee has a list of 17 non-self-governing territories that includes Guam. It oversees the right to self-determination, which was inscribed into international law with the adoption of U.N. Resolution 1514 in 1960. The resolution proclaimed “the necessity of bringing to a speedy and unconditional end colonialism in all its forms and manifestations.”

The U.S. was a signatory of this resolution and yet still hold three of the 17 non-self-governing territories. [Puerto Rico and the Northern Mariana Islands are not included due to complicated legal reasons but remain monitored by the committee.] They were a signatory and yet when a resolution to give Guam the right to self-determination — the right for Guamanians to have a say as to whether or not to be part of the U.S., an option that was never given to them — was presented before the U.N., the U.S. voted “no”.

According to a representative for the U.S., they respect Guam’s right to sovereignty but voted against it because the U.S. delegation felt the language of the resolution to be aggressive towards the U.S.. According to history, however, the U.S. has aggressively decided to not respect the sovereignty of Guam or the safety of its people. According to history, the U.S. has aggressively demonstrated its willingness to dominate and exploit Guam. Is that not what colonialism is? Is that not the hideous thing we learn about in history lessons about the British or the Spanish?

However, there is more on the line than just Guamanians’ sovereignty. Their lives and lands are being jeopardized and used as pawns in a cold war between the U.S. and North Korea, between President Trump and Kim Jong Un. It’s fair and well to exchange heated tweets when the people at risk by a possible nuclear strike are shrouded by the presence of the U.S. military and a history of colonialism.

As independence advocate, Victoria-Lola Leon Guerrero said at the U.N. meeting: We are told to make way for more military bases because the U.S. needs us for their defense. We cannot wait another decade to eradicate colonialism.”

So if Chamorros and other Guamanians are targeted by a missile, which party really put the target on their back?

Featured Image Source: The U.S. Department of Defense

Be First to Comment