“Crime wave” is the phrase that surrounds the newest set of criminal justice policies passed by New York and California. If you look up “bail reform” on Google, the first page of results reveals a host of articles in which it is a keyword, authoritatively bolded. There are publicly available transcripts of police chiefs in a smattering of cities pointedly insulting the representatives who enacted these bills. It’s understandable that the policy isn’t gaining the level of traction its proponents expected. But while the public argues over crime statistics, it’s missing the central debate around bail reform.

The United States has the highest rate of incarceration in the world. Two point two million inmates are held across the nation’s jails. The prison population has grown 500 percent in fifty years. The crime rate hasn’t. While many point to Reagan-era policies as the chief drivers of modern prison growth, they ignore the other tremendous pipeline sustaining mass incarceration: the cash bail system. In 2017, only one-third of those held in the nation’s jails had been convicted of a crime. The other two-thirds were in prison as a punishment for poverty, not criminal activity. These inmates, unable to pay the price of their freedom set by the courts, were the victims of a rapid surge in bail prices across the nation.

While the number of inmates in U.S. prisons has increased across every demographic, changes in incarceration rates have not been felt equally. In 2016, African Americans were almost six times more likely to be incarcerated than whites. Many write this off as the result of racial profiling, overpolicing and the unfair enforcing of the same War on Drugs policies that were purported to have caused the prison population increase. However, largely ignored is the fact that Black Americans are routinely charged with higher bail amounts than white defendants facing the same charges, even when confounding variables are taken into account. The disparities in bail prices are hardly insignificant, averaging around ten thousand dollars.

Both because of the costs generated by the massive increase in the prison population and because of the civil unrest generated by appalling and unjustified racial disparities, many states have begun searching for ways to simultaneously limit the number of inmates in their prisons and minimize racial disproportionalities within these populations. One way they’ve chosen to pursue these objectives is bail reform.

Bail reform policies, on a surface level, seek to limit the number of pretrial inmates held in a state’s prison facilities by changing the metrics that determine whether an inmate receives bail. Currently, most prison systems in the United States operate using a cash bail system, wherein a monetary payment set by a judge is the condition that must be fulfilled in order for a defendant to receive bail. While this policy has existed latently for over a thousand years, the recent increase in bail prices has made it infeasible, and it now threatens to destroy the foundation of “innocent until proven guilty” upon which our criminal justice system was built.

Bail reform policies shift the conditions defendants must meet to receive bail away from cash and towards a risk assessment system in which several factors statistically correlated to criminal and flight risk determine whether a defendant should be released pending their official criminal trial. Ultimately, the use of risk assessment bail is intended to keep dangerous pretrial defendants off the streets without punishing harmless offenders. However, the relative newness of risk-assessment bail means that there is a severe lack of research on its overall efficacy — especially in terms of its effects on racialized incarceration.

Despite the missing quantitative analysis of the relationship between bail reform and the racial composition of America’s prison population, several prominent authors have argued both in favor of and against bail reform as an antidote to the racial bias ingrained in the pretrial process. Pulitzer Prize recipient Jonathan Schuppe has been a vocal supporter of bail reform, arguing that even if risk algorithms are not perfect, they force bias into the open in such a way that it can be pinpointed and ameliorated. Schuppe’s argument is logically sound; bail reform policies eliminate the avenues through which Black defendants are surreptitiously conditioned for prison.

However, blind faith in a broken system may not breed the colorblind outcomes Schuppe and others hope for. One concern with risk assessment algorithms is that they test subjective factors like “danger,” opening the floodgates to biased assessments of defendants rooted in racial stereotypes. Schuppe may be correct that bail reform would at least move these stereotypes into the open and eventually force America to confront them, but it’s unclear why that is worth the very real cost of sending tens of thousands of harmless black defendants to prison to await trial indefinitely because they are somehow “dangerous.”

Perhaps the most glaring flaw with risk assessment algorithms is that they use old data to determine flight and criminal risk. It is not debatable that the criminal justice system is riddled with racial bias — Black neighborhoods are woefully overpoliced, Black residents are empirically more likely to be stopped by police at traffic stops, mandatory minimums target Black Americans in devastating ways, and the arrest rate is significantly higher for Black Americans than it is for any other demographic. All of these factors significantly increase the likelihood that Black defendants are categorized as dangerous, and thus receive high risk scores, even when they pose very little actual risk.

While these critiques may be valuable insofar as they provide a foundation upon which to test bail reform, answering the question of whether bail reform is an example of incremental progress or a step back into the Reagan era necessitates empirical evidence. New Jersey acts as a practical case study through which to test these hypotheses. It has proven to be the best state to gather data from both because it was one of the first states to implement bail reform in 2016 and because its iteration of bail policy has acted as a model for bail reform legislation nationwide.

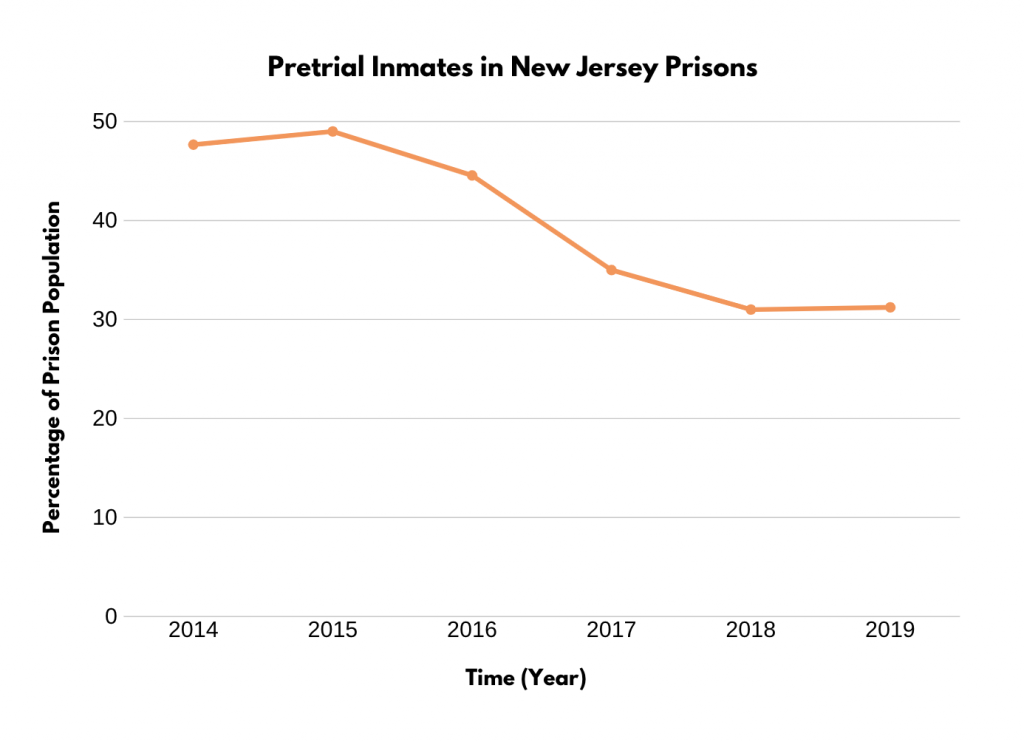

Although New Jersey represents only one of fifty state prison systems in the U.S., data from this iteration of bail reform should be regarded as both a warning and a beacon of hope for the rest of the nation. A statistical analysis of data provided by the New Jersey Department of Corrections reveals that from 2014, two years before New Jersey implemented its bail reform policy, to 2019, three years after implementation, New Jersey’s prisons witnessed a significant reduction in their pretrial inmate populations. This should give hope to all those legislators currently pushing bail reform policies; at the very least, bail reform offers a solution to the prison overcrowding that has resulted from the massive prison pipeline created by cash bail.

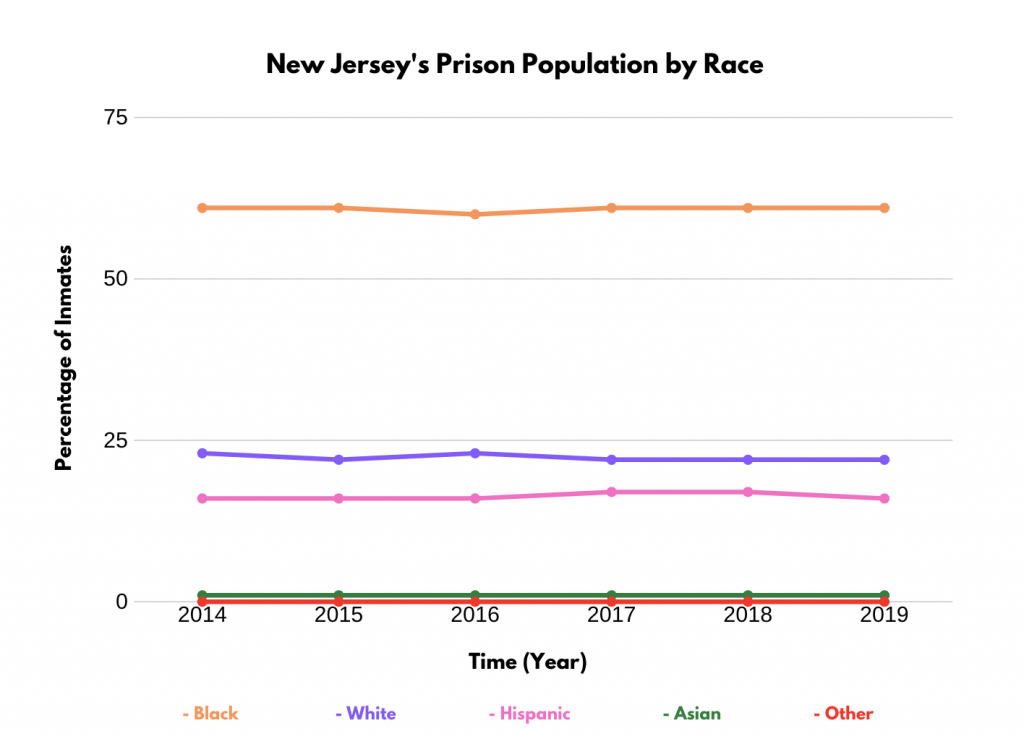

The racial composition of prisons, however, saw almost no change, indicating that these policies were not the sweeping success proponents such as Schuppe had hoped for. Fluctuations in all racial categories remained within one percent, indicating no statistically significant changes within the time period examined. While the findings presented earlier regarding the size of the pretrial population indicate that this group has made up a minority of the prison population in all years examined, pretrial inmates have consistently composed a significant enough percentage of the population that they certainly impacted its racial composition. While they likely have a slightly different racial makeup than the entire population, any statistically significant changes within this subgroup would have been reflected, if slightly muted, in the prison population writ large.

Despite bail reform’s lackluster impact on the racial composition of prisons, there is reason for optimism. The data reveals no increase in racial disparities in the prison population, which should alleviate critics’ worst fear — that bail reform policies would exacerbate racial disparities by relying heavily on racially biased assumptions of defendants. On the surface, this still doesn’t offer much hope; bail reform is certainly falling short of pushing biases into the open in the ways its proponents had hoped. However, it is worth considering that this is a better outcome than sending non-dangerous Black defendants to jail simply for being Black. Perhaps, then, this does provide reason for optimism; risk assessment is not a step in the wrong direction and still holds the potential to create positive change if the criminal justice system is ready to go beyond piecemeal reforms.

Featured Image Source: Leonard Freed

Comments are closed.