Standing in front of the steps of the Washington Monument in 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. declared, “America has given the Negro people a bad check, a check which has come back marked ‘insufficient funds.’” King used this metaphor in his famed “I Have a Dream” speech. Perhaps more revealing than Dr. King’s quote, however, is the title of the event where he gave his speech: the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Jobs and Freedom. King knew that the two were inextricably linked — in order to end the scourge of anti-Black racism, the barriers of race and class had to come down. His dream would not be realized without a significant restructuring of the economy.

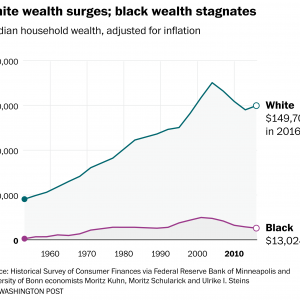

King understood then what Black Lives Matter activists are railing against now: that the wealth gap must be closed in order to achieve true racial equality. In fact, in 1968, the typical middle-class black household had $6,674 in wealth; the typical white middle-class household had $70,768. In 2016, that number for Black households was $13,024. For white households: $149,703. After a slate of civil rights reforms, the racial wealth gap had somehow increased.

Today, as the movement for Black lives has reached a fever pitch, protests have re-awakened the American psyche and called on the country to begin solving its racial problems — chief among them? The gap in wealth. The number has been repeated so many times that it’s almost cliche: the net worth of the typical white family is ten times the wealth of the typical black family.

How We Got Here

While the history of America has been well-documented, it’s worth illustrating the devastating effects of America’s original sin, slavery, in economic terms. As Yale Professor David Blight notes, at the time of emancipation, “the nearly 4 million American slaves were worth some $3.5 billion, making them the largest single financial asset in the entire U.S. economy.” Of course, this has a debt that this country has never repaid. General Sherman’s famed Special Order No. 15 promised 40 acres and a mule to former slaves, but the order was later killed by President Johnson.

The effects of that decision were monumental. Those newly freed could have gone from unpaid labor to landholders themselves. Instead, after the ratification of the 13th Amendment, Jim Crow practices like debt peonage and convict leasing maintained African-Americans’ status as second-class citizens and precluded Black wealth from growing. The language of oppression changed, but the central desire of keeping two Americas remained wholly intact. That second-class citizenry continues to this day. A 2011 study by the Economic Policy Institute found that 87 percent of American occupations can be classified as racially segregated and that black men earn 71 percent of what white men make. In short, whiter jobs mean higher wages. Whiter jobs mean more freedom.

As the 19th century rolled into the 20th, forms of discrimination evolved, further entrenching the racial wealth gap in America. In the New Deal era, de jure segregation was most apparent in the GI Bill and FHA loans, both of which systematically excluded African-Americans in their reach. While these policies are rightly condemned, they illustrate an intriguing dynamic between the Democratic Party’s inclusionary vision of class and its exclusionary vision of race. Professor Toure Reed argues in his 2020 book Toward Freedom that although some New Deal programs were “marred by discrimination,” other regimes overrepresented their numbers: hundreds of thousands of African-Americans, for instance, acquired work through the Civilian Conversation Corps, Public Works Administration and Works Progress Administration. In this instance, then, there lies a clear tension between social redistribution making the country more equal and racial exclusion undermining that vision. While Reed’s factoid is noteworthy, homeownership remains to this day the ticket to the middle class. President Roosevelt’s expansion of the welfare state was a tremendous accomplishment, but that success makes the New Deal’s exclusion of African-Americans all the more pernicious.

Twenty years later, President Lyndon Johnson’s War on Poverty and passage of major civil rights legislation signified the next great expansion of government power. In terms of the racial wealth gap, however, their effects were mixed. Though FDR was President Johnson’s hero, the War on Poverty was far more limited than the New Deal. As Professor Robert Manduca showed in a 2018 study, from 1968 to 2016, Black-white disparities in family income narrowed by a third; however, this positive trend was entirely negated by a countervailing force: income inequality. Future presidents did little to address this problem. Richard Nixon touted a policy of “racial capitalism,” which, as UC Irvine Professor Mehrsa Baradaran illustrates, gave miniscule aid to Black businesses and was “utterly unresponsive to the needs of the Black community.” Today, three-quarters of the wealth amongst both whites and Blacks are held by the richest 10 percent. For the past half-century then, those in power have pursued policies hollowing out the middle class — and Black wealth in particular — all while couching those actions in the language of anti-racism.

These issues persist to this day and are especially apparent in one of the great catastrophes of the 21st Century: the Great Recession. The economic disaster precipitated a foreclosure crisis in which African-Americans lost their homes at twice the rate of any other racial group. Eerily reminiscent of the practices of the 1940s, the crisis was partially a result of lenders targeting African-Americans for riskier loans. In fact, just two years ago, financial regulators noticed that Bank of America was redlining in Philadelphia. Class was a factor here too, however: the Obama Administration was notably reluctant to provide relief to homeowners, which disproportionately hurt the most vulnerable Americans.

This history clearly shows the dual dynamics of race and class working — at times separately, at times in tandem — to create the racial wealth gap we see today. While the racial wealth gap is clearly part of our larger problem with income inequality, there are also explicitly racial forces at play. A 2015 study by Michael Gaddis of UCLA found that African-Americans who attend highly selective universities get job offers akin to their white peers who attend less selective institutions. Additionally, Gaddis found, when employers respond to Black candidates, their offers come with lower starting salaries and with jobs that carry lower prestige. To begin solving this problem, then, requires an approach that combats wealth inequality, racism and the intersection of the two.

Where Do We Go From Here?

Because of the class dynamic, certain race-neutral solutions would significantly close the wealth gap. One oft-discussed proposal is baby bonds, an idea initially developed by Professors Darrick Hamilton and Sandy Darity and proposed by Senator Cory Booker during his presidential campaign. The concept is simple, as The Atlantic’s Annie Lowrey lays out. The government creates investment accounts for children, giving babies born to poorer families more money and babies born to richer families less. “Black families,” Lowrey continues, “need wealth. The government could just give it to them.” Baby bonds’ effect on the racial wealth gap would vary with the size of the program, but one study from the City University of New York finds that the policy could “reduce the wealth held by young white adults from 15 to 1.6 times the wealth held by young Black adults.” In a similar sense, other progressive policies — raising the minimum wage, enacting universal healthcare, reforming the tax code — would make smaller but meaningful reductions in the racial wealth gap.

The more contentious area of policy has been race-conscious solutions, most notably reparations for slavery. The most famous argument for them was outlined by Ta-Nehisi Coates in The Atlantic in 2014. Framing the issue as one of holding the guilty party — the American government — culpable, Coates explains that the question of reparations is about “whether we are courageous enough to be tied to the whole of our past.” Beyond this moral case, however, lies an economic one. In a paper for the Roosevelt Institute this year, the academics Kirsten Mullen and William Darity propose a ten trillion dollar plan, which would cut the chasm in Black wealth and white wealth by 74 percent. Given the astronomically large sum it would take, this measure will likely never be taken up by Congress, but even a much smaller-scale program would make a sizable difference in the wealth gap.

Then and Now

The day before his death, Dr. King gave a speech now seen as prophetic: “I’ve seen the Promised Land,” he said. “I may not get there with you. But I want you to know tonight, that we, as a people, will get to the Promised Land.” James Earl Ray killed him the next day.

Dr. King was tragically prophetic in another way too. In 1963, he spoke of that metaphorical bad check at the March on Washington. In 2020 — fifty years later — George Floyd walked into a grocery store and wrote one for $20. Suspecting Mr. Floyd was counterfeiting the money, the store clerk called the police, leading to the infamous encounter where police officer Derek Chauvin killed him in eight minutes and 46 seconds. The “bad check” had taken away much more than Mr. Floyd’s freedom. The ruthless cycle of race and class had taken George Floyd’s life.

57 years later, our country has made progress, but the dream for equality is far from realized. Looking forward, however, the Black Lives Matter movement offers hope that America may have an anti-racist majority for the first time in our history. Indeed, in the months following the deaths of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, institutions changed their racist names, Confederate monuments came down, and NBA players went on strike to protest racial injustice. If this is all that results from our racial reckoning, however — as important and overdue as these things are — we will have failed. Until we address the racial wealth gap, Dr. King’s check will still be marked insufficient funds.

Featured Image Source: Zora J. Murff, New York Times

Comments are closed.