Covid-19 has undoubtedly harmed our most vulnerable communities disproportionately. This effect has not just been seen on overall public health— it is also apparent throughout our education system. Due to the structure of public school funding, each school throughout the state differs enormously with varying degrees of resources. Public schools are beginning to face unprecedented questions: when should children return to in-person learning? And how can we return safely and equitably?

School re-openings have sparked a debate across America, across California, and across the East Bay region. Most agree that children undoubtedly are not doing well without the in-person component, but the debate is open on whether this takes the priority over health and safety.

The debate has been dominated by more privileged families, often speaking on behalf of Black, Latinx, and low-income communities that they cannot speak for. They have continued to argue that reopening is in the best interest of all students, regardless of the potential consequences on those most at risk. While schools could potentially open safely relatively soon, there is no point in rushing when personal protective equipment (PPE), precautions, and vaccinations are not ready yet.

There are many issues when it comes to opening schools. One of the biggest considerations is community safety, the most obvious being that it will undoubtedly lead to more COVID cases, especially in communities with fewer resources. This would cause continuous harm to the most vulnerable communities and their lack of healthcare access. Low-income and non-white individuals are the most likely to be uninsured, and many also face inadequate service, especially when healthcare facilities are so overworked. A full reopening of schools would lead to further strains on local hospitals and communities.

Another huge consideration in the debate are teachers and other education employees. Teachers and faculty are not fully vaccinated yet, and their concerns about their health and their students’ and families’ health should be the top priority. We should not expect teachers to return until fully vaccinated; they should not be put unnecessarily at risk.

Currently, California says vaccinating teachers is not a prerequisite for resuming in person learning, but it needs to be. This blatant disregard for teachers’ health will continue to harm and exacerbate current inequities. Regardless of PPE, teachers should not be expected to make a sacrifice for their health. PPE does not equate to the same safety being fully vaccinated would provide. It will only cause more stress on strained communities— healthcare systems, essential workers, and low-income schools.

Those who have been outspoken against a rushed reopening include teacher unions and community activists. Many who are pushing to open public schools are casting doubt on teacher unions’ morals. Parents advocating for a reopening have gone so far as to demonize these unions, even claiming that these unions are a part of a “political machine.” These claims are disappointing and wrong; teachers are one of the most underpaid and overworked professions. No one should be put into a situation where they must risk their lives for their income, regardless of their profession. Comments like these are trying to tear down the credibility of unions, but this situation has only proved how necessary these unions are; without it, teachers would have been forced into a situation of risk. The parents discrediting teacher unions in support of the earliest possible re-openings are mostly wealthy and white. These parents have even had multiple rallies pushing for schools to reopen while also casting blame on teachers for delaying openings.

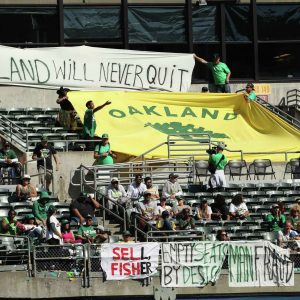

At a February 28th rally in Oakland, Mayor Schaff made an appearance and voiced her support for reopening. Reporters who attended the rally claim that a majority of attendees do not live in Oakland, and that there were no Black people in support. This reality sadly aligns with what has been observed of the reopen advocates; white parents speaking on behalf of all parents and students.

The Berkeley Unified School District has recently announced a new school reopening plan. Middle and high school students in Berkeley will return to a hybrid model for four hours a week of in-person learning in mid-April. Elementary students may begin attending school for a full five days a week starting late March and early April. The group BUSD Parents for Open Schools praised this new elementary school reopening plan, but are frustrated that this plan is not being implemented for middle and high school students. These parents have continued to lead protests against the school district fighting to get all students back in school, full-time. Many are hesitant at the prospect of a full reopening for secondary schools, as experts and the CDC guidelines have claimed that such a change would be too risky.

Wealthy parents have continued to argue that kids are losing out on precious opportunities, and that closures are not necessary as their schools can reopen safely. They argue that schools have adequate access to resources and families have easy access to healthcare services.

Additionally, these parents argue that kids’ mental health is declining due to the ongoing virtual instruction, and therefore the kids need to get back to the in-person routine. While studies have shown that kids’ mental health has suffered from the pandemic, it is unclear whether an altered return to in-person learning would be a solution to this. A more direct solution to this problem would be providing mental health services to youth, which would be a safer and better use of resources to tackle this real problem.

This debate has put on display existing school segregation, racism, and their lasting effects which are disproportionately affecting Black children. Education quality is significantly based on your residence; and your education quality is a major determinant for future success. Education funding is significantly based on local taxes, therefore more wealthy communities will have better schools, and poor communities will have fewer resources and therefore will be worse off. In addition, geographic mobility is continuously declining; where you are born is increasingly more likely where you will live for the majority of your life. People in low-income areas cannot afford the housing costs in high-income areas, leaving them stuck in these poor communities, forcing them to enroll their students in impoverished schools.

Take the example of Oakland and Piedmont public schools. Piedmont is a city completely surrounded by Oakland, with some even calling it “an island of wealth.” Piedmont Unified School District’s total revenue per pupil is $17,725 while Oakland Unified School District’s is $12,721. Piedmont has 40 percent nonwhite enrollment, while Oakland has 90 percent nonwhite enrollment. Oaklands poverty rate is 18 percent and Piedmont has a rate of 2 percent. Kids living in these two cities have completely different educational experiences despite their proximity.

Oakland and Berkeley’s school districts have both faced continuous pressure to reopen, but the teachers unions have stood strong against the pressure and are demanding vaccinations before a return. These schools do not have the level of resources, funding, or access to healthcare that wealthy districts like Piedmont have. Obviously, this situation has pointed out even more inequities than just health disparities, and Piedmont’s ability to open safely earlier than other poorer districts shows once again the need to change the structure of school funding.

These lasting effects of segregation already determine future outcomes to an extent, such as health and wellbeing, and now COVID-19 is further exacerbating and stressing them. If schools are unable to prioritize health and safety, they should not open; they are only putting our most vulnerable at risk.

Featured Image Source: Yasmine Gateau for NPR

Comments are closed.