In April of 1969, the University of California purchased the site that is now People’s Park. Located just blocks away from the University of California, Berkeley campus, People’s Park has been a community center for refuge, recreation, and political activity since its very origin. Today, the University wants the Park gone more than anything – a prospect inciting fierce resistance by activists, including 24/7 occupation of the Park.

The University originally reserved this land as a green space for public recreational use. However, the University has always had its eye out to use the park as a space to build and profit off of student housing. After nearly half a century, the University is pushing through with housing development plans and demolition of People’s Park – though not without significant resistance. This is because the Park has long been a home to much of Berkeley’s unhoused population. For years, Park activists have defended these residents and engaged in non-violent resistance, including against military intervention, to challenge the University’s attempt in executing development plans. The park, activists claim, is cherished as a home to unhoused residents, as one of the few remaining green spaces in Berkeley and as a significant historical and cultural symbol.

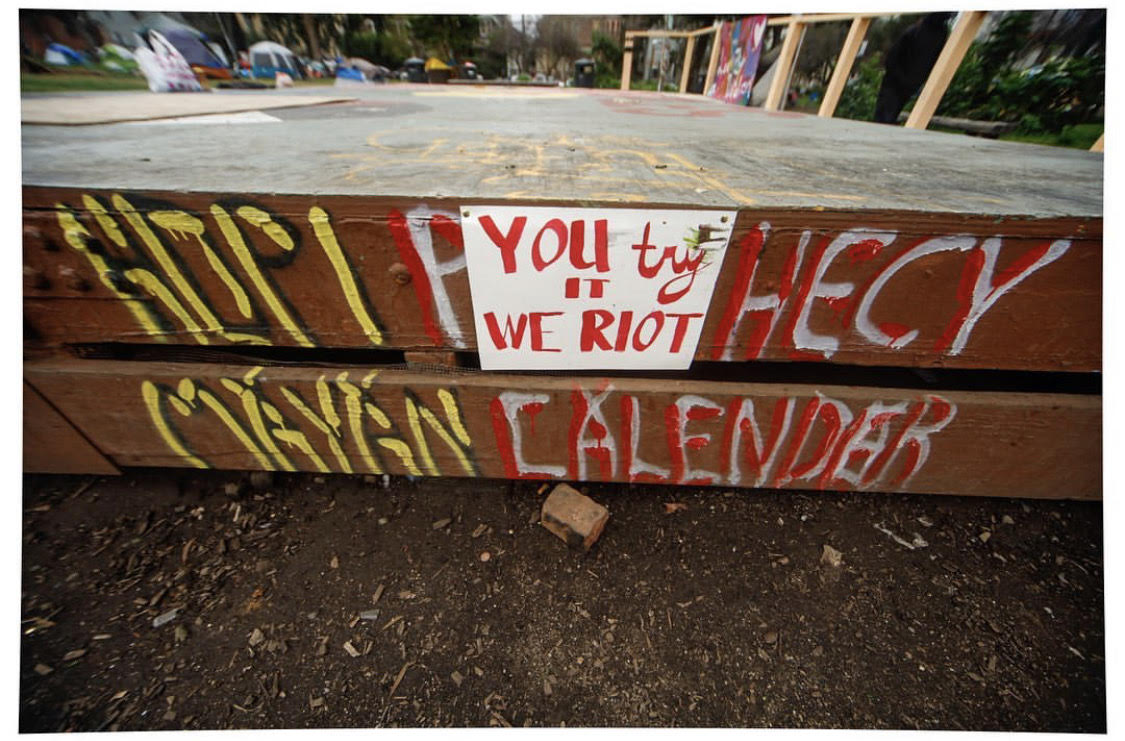

UC Berkeley Chancellor Carol Christ formally announced in 2018 the newest plan to develop People’s Park into student housing. In response, Park supporters have staged demonstrations and organized to obstruct the University’s plan to begin development. The stakes rose on January 30, 2021, when protestors decided to tear down fences (which were put up by the University) and to begin 24-hour-7-day-week occupation of the Park.

On February 22, 2021, Christ issued a statement sent to all University undergraduate and graduate students, faculty, and staff, regarding the proclaimed “need” to construct student housing on People’s Park. In that statement, the University announced that it is (in response to the criticism of People’s Park advocates) indeed attempting to “support the unhoused people who use the park.” This support, however, merely entails the hiring of a single social-worker and permission for a non-profit organization to also construct low-income housing on People’s Park. This housing, however, is not reserved for currently unhoused residents living in the Park. In fact, the University’s provisions ultimately do not commit to ensuring all (approximately 100-150) currently unhoused residents living in the Park will obtain some form affordable, long-term housing.

For this reason, student and community organizations in Berkeley quickly challenged Christ’s decree. Groups putting out official statements include The Associated Students of the UC**, The Daily Californian, The People’s Park, Berkeley Student Cooperative, The Suitcase Clinic, Mariachi Luz de Oro at Berkeley, Hermanos Unidos at Berkeley, Black at Berkeley, The Free Press Project, among others. Across these groups, activists claim that the University’s proclaimed “need” to build additional housing on this land is merely an excuse to displace the unhoused population residing in the Park. They maintain that the University’s plan (even with low-income housing options) would contribute to the on-going process of gentrification in the Bay Area, as well as worsening environmental conditions.

So why is UC Berkeley– a prosperous and politically powerful institution– unable to propel its plans and override the organizers’ efforts? While neither the University’s attempt to build on the park, nor the efforts to resist development of People’s Park are new, there has been one significant development in recent years: the strategies of political organizing now demonstrated by Park activists – even through a pandemic – have evolved to become even more participatory and direct. That is, with activists united more than ever, the University’s attempt to develop People’s Park has never been so frail.

In many cases, nonprofit organizations are the default, dominant forces for organizing political action (recall the role of Black Lives Matter** in the racial justice protests that took place throughout 2020). Especially among leftist groups, however, non-profit organizations have met fierce criticism for major shortcomings in achieving set goals.

Dylan Rodriguez, a professor at the University of California, Riverside, coined the term Non-Profit Industrial Complex in an article challenging the dominant role of nonprofit organizations. Within progressive-leftist organizing, this term is increasingly being used to describe the disconnect between nonprofit organizations (who are often white, middle-class individuals working for a paycheck) and the people they “advocate for.” Given that non-profit professionals are often in positions of privilege and approach social-issues as a means of labor, this disconnect can weaken the unity needed in collective, grassroots movements, as well as the momentum or sense of urgency among “workers” of social movements.

However, Park activists have demonstrated a remarkable ability to organize collectively– combining the efforts of non-resident Park activists and the Park residents themselves. In fact, at weekly General Assembly meetings held at the Park, unhoused Park residents and community members alike can be heard openly expressing their sentiments about the development plans. After such discussions, wholesome community dinners, sports activities, musical festivities, and movie screenings take place– open to any members of the public. Non-resident Park activists always thank Park residents for permission to be on the site, rather than feeling entitled to be there.

The political organizing strategies used by activists at People’s Park reflect new models in organization theory, such as mutual aid networks. The work of various collectives practicing mutual aid in the Park traces back to even before January 30 of this year. Currently, these groups (notably the Berkeley Student Food Collective, Berkeley Mutual Aid Projects, Food Not Bombs, The Suitcase Clinic, and more) are collecting and distributing communal supplies such as food, water, and other essential items, as well as providing 24-7 emergency medical care on site.

The behavior of these groups reflect mutual aid networks. In a new book on mutual aid, Dean Spade, a professor at the University of Seattle School of Law, describes mutual aid as “ordinary people […] finding bold and innovative ways to share resources and support the vulnerable.” As a form of political organization, mutual aid is steadily gaining popularity because such direct strategies effectively accomplish the goals groups seek to achieve. For example, non-resident Park activists envision a world in which Park residents are respected with autonomy – and this they do.

Because this political organization strategy collaborates with the victims of development plans, the commitment to resisting University encroachment is more formidable than ever before. These activists are willing to occupy the Park even when the sun goes down, in order to truly empathize with the permanent Park residents. In essence, mutual aid projects encourage activists who are not directly victims to step into the shoes of the vulnerable. This shared understanding and collective organizing allows for powerful and collaborative mass-movements to be created and sustained.

All of this is not to say that Park activists are progressing without obstacles. The COVID-19 pandemic has inhibited the ability of Park activists to physically organize in mass numbers. At General Community meetings (which take place every Friday), community members and Park residents attempt to discuss organizing plans while adhering to social-distancing guidelines. But, with numbers of people spaced 6-feet apart, some participants end up far away from the speaker and disengaging.

And, keeping activists and community-members engaged long-term is an even greater difficulty mutual-aid projects and similar forms of grassroots organizing often face. Even the most successful and prominent mutual aid projects, such as the Black Panther Breakfast Program, often collapse simply due to loss of commitment and unity among activists. Indeed, history suggests that the durability of mutual aid networks withers most with uncoordinated internal organizing, rather than external pressure. Surprisingly, various state efforts to suppress the Black Panther Breakfast Program, like state officials urinating on the food for children, actually encouraged more community members to participate in the program.

For this reason, some hypothesize that state interference in mutual aid projects can actually bolster the strength of activists. Therefore, as strong and united as Park activists may now seem, the simple fact that neither UC Berkeley nor the UC Police Department have officially retaliated or directly confronted activists in weeks hints at an equally powerful strategy: waiting for non-resident Park activists to wear down, and eventually, disband.

But Park activists have some advantages as well. Combined with contemporary social media technology, Park activists are newly capable of mobilizing people and disseminating information to large numbers. Just one post (pictured above) made by a popular Instagram account with over 1.3 million followers demonstrates just how sizable and committed activist networks behind People’s Park may truly be.

Across social media platforms, many organizations have posted or re-shared posts made by the Park’s Instagram account (@peoplesparkberkeley). Though numerous, these posts all assert one common message: the University’s development plans are a threat to valued public space and the well-being of all Bay Area residents – particularly low-income, unhoused, and Black and Brown communities.

In addition, mobile payment services such as Venmo and online crowdfunding sources such as GoFundMe are being used to sustain activist efforts in unprecedented ways. Since the launch of Venmo only a decade ago, direct mobile payments have become an increasingly popular way to directly meet others’ survival needs (particularly of queer, trans, and Black and Brown communities). Indeed, Park activists are sure to promote their mobile payment funds, and use those funds to provide food, water, toiletries, as well as medical services for Park residents and non-resident Park activists.

For now, these activists at the Park are committed and collected in their fight, putting out official demands this March. What they accomplish in the face of the University is dependent on the strength and numbers of everyday community members who decide to show up for, spread information about, and share resources with the victims of University’s development plans. Fortunately, mutual aid organizing is premised on the fact that all of us are victims to plans that displace marginalized communities and propel environmental degradation– and that all of us can contribute to the efforts of Park activists by donating our services, our resources, or our time. “This is our home,” said Aidan Hill, a prominent Park activist. “And we will protect our home, by any means necessary.”

**Titles for identification purposes only

Featured Image Source: Berkeley Political Review

Comments are closed.