We have all been fed a lie: “Education is the great equalizer.” That line dominates the public discourse on K-12 public education. However, it’s certainly not true in the Bay Area nor in California.

Piedmont High School and Oakland High School are less than 3 miles apart. Yet the academic performance of their students couldn’t be more different:

Piedmont High School and Oakland High School Academic Performance

| Piedmont High School | Oakland High School | |

| Reading Proficiency | 87% | 37% |

| Math Proficiency | 82% | 12% |

| Graduation Rate | 99% | 82% |

| Average SAT score | 1340 | 1000 |

| Average ACT score | 31 | 22 |

This inequality exists throughout California. Why?

According to the two education experts I talked to—Niu Gao and Julien Lafortune from the Public Policy Institute of California—K-12 education inequality persists in California and we lag behind the rest of the nation because of what happens at schools and what happens at home, but mainly the latter.

First, what happens within schools? According to Gao, of all factors within schools, “The single most important one is teacher quality.” The more experienced teachers benefit students the most. Before COVID-19, California was dealing with a teacher shortage, which has only worsened during the pandemic as California teachers have retired at record numbers.

High-need school districts face chronic shortages of experienced teachers and have high teacher turnover: in underserved districts, “Students come in with lots of needs, not just academic, but also social and also emotional. They [come] in hungry and they are sick. They don’t have anyone home to feed them. So teachers in those communities actually have a lot more unmet needs to take care of.” It’s hard to succeed if you’re hungry, have something going on at home, and if your teachers are always new and aren’t very experienced.

Experienced teachers don’t earn enough money to incentivize them to stay, so they leave, and less experienced teachers take their place. Teachers generally prefer to be at wealthier schools, where they have more resources and support and the neighborhoods are nicer and their salaries are higher.

Poor school districts often face what Julien Lafortune calls the “Class size versus teacher experience trade-off.” With limited resources, school districts face a dilemma. More experienced teachers are expensive to hold onto, so districts must decide if they want a small, but more experienced teacher cohort, or a larger, but less experienced teacher cohort. With a smaller cohort, classroom sizes go up, but the teacher is more experienced. On the other hand, with a larger cohort, classroom sizes fall, but so does teacher experience. So, districts must decide if they want larger classroom sizes headed by more experienced teachers, or smaller classroom sizes headed by novice teachers. Smaller classroom sizes aren’t always best.

Gao and Lafortune agree that more school funding is needed to enable high-need districts to hire and retain experienced teachers, as well as fund academic programs (such as tutoring) and support systems (such as mental health counselors). With that, schools are in dire need of more funding for programs to train local young people to become future teachers, especially in rural areas where there simply aren’t enough teachers around.

Gao explains, “If schools have more money, they can hire more experienced teachers, more qualified teachers… And also with more resources, schools can provide more academic programs and also other support programs… If we’re thinking about COVID-19 recovery, we know that social and emotional learning is a huge issue and schools need the money to, for instance, hire a counselor and provide those therapy sessions.” Lafortune believes we need to make teaching an attractive profession because right now, it isn’t. He calls for bonuses for experienced teachers who work in high-need schools and districts, as well as higher pay generally.

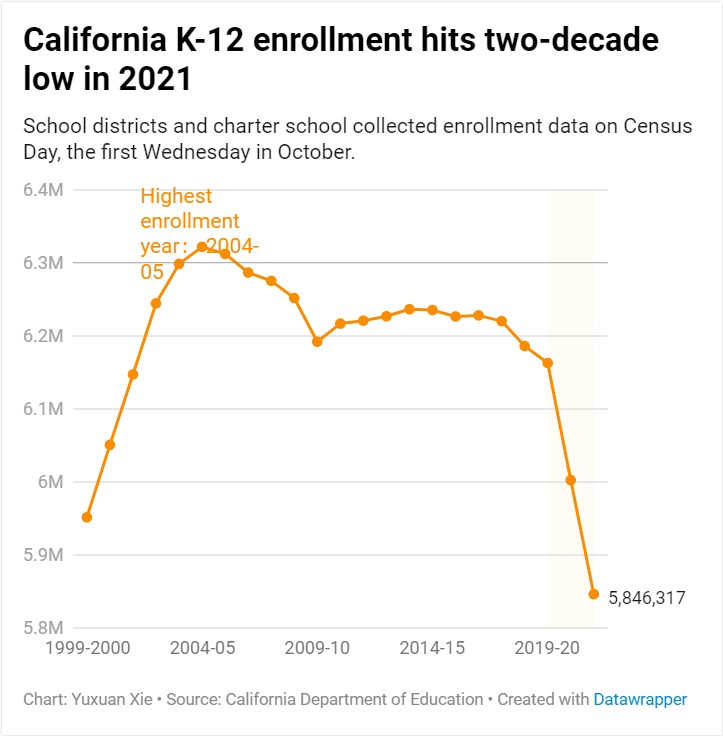

Another factor exacerbating California’s funding problem is long-standing enrollment decline as people move away from the coast and more inland, put their children in private school, leave the state, or drop out. The enrollment decline has precipitously accelerated during the pandemic. Parents often decided not to send their child to kindergarten during COVID-19 and waited for things to improve, accounting for most of the enrollment decline. Since school funding is per pupil, the less kids in the system, the less money districts have for teachers and other programs.

There is additional evidence that funding is a huge problem in California. Nationally, for Fiscal Year 2020, California ranked 44th in per-pupil funding adjusted for cost of living. The fifth largest economy on Earth spends less on K-12 education per student than every other state except six. California spends less on K-12 education per pupil, adjusted for cost of living, than Mississippi, the poorest state in the nation. Let me repeat: In 2019, California, which then had the 4th highest GDP per capita of any state in the United States, effectively spent less on K-12 education than Mississippi, the state with the lowest GDP per capita. How is this possible?

One answer is that the way California finances education hurts students. Most K-12 education funding comes from state income taxes, disproportionally paid by wealthy Californians. When incomes of wealthy Californians plummet, like during the 2008 Great Recession, so does school funding. The future of the state shouldn’t pay the price for the irresponsibility of the top 1%. During recessions, more people enter poverty. However, schools—a key vehicle out of poverty—lose funding. Lafortune notes California is always playing catch up to the rest of the nation. A recession hits and California education spending nosedives. With economic recovery, spending increases again until the next recession and the cycle continues.

Gao proposes that California should follow New Jersey’s lead (when we’re looking to the butt of America for help, you know we are in deep doo doo, no pun intended). To fund education, New Jersey relies more on property taxes, which aren’t as volatile as income taxes. Gao says, “Because Prop 13 really limits how much money can go to schools, we probably would be in a different place if we were actually funding schools like New Jersey [does].”

Prop 13 is a 1978 ballot proposition in California that slashed and capped property tax growth. This was during a time when property taxes caused some California homeowners to no longer be able to afford their homes. So they get kicked out of their own homes. However, since California public schools received most of their funding from local property taxes, a byproduct of Prop 13 was that schools lost lots of revenue.

Lafortune agrees that Prop 13 is a huge problem: “These constraints on local revenues… that has a huge impact.” However, he believes California policymakers share the blame: “I think a lot of people will point to [California’s underperforming schools] and say it’s all Prop 13. But there were subsequent decades of state choices as well.” He cites Prop 4 in 1979, also known as the Gann Limit, which capped state spending on education. It has since been rolled back by Prop 98, passed in 1988 that mandated that 40% of California’s budget goes to K-12 education and California community colleges.

We later discussed Serrano v. Priest (1971) and other court cases regarding education. Serrano was one of many court cases brought by parents who sought to equalize K-12 education funding between wealthy and poor school districts. In a system at the time where most revenue for schools came from local property taxes, naturally the richer areas had way better funded schools than poor areas.

The California Supreme court eventually ruled in these parents’ favor, equalizing education funding by district. However, according to Lafortune, California only achieved this equality by bringing down spending of higher income districts, not raising spending of lower income districts.

Lafortune summarizes it nicely: “We’ve kind of imposed a lot of these constraints on our ability to spend more and raise more. Part of it’s Prop 13, but it’s also kind of other things, other constraints we’ve imposed over time.” Basically, we Californians—politicians, voters, everyone—have continually shot ourselves in the foot. Of course.

However, talk of money can be deceiving. California sought to address school funding in 2013 by implementing a new school finance system called the Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF), which increased funding for districts with more low income students, English learners, and foster youth, and gave school districts more control over spending.

According to Lafortune, evidence on LCFF’s success is mixed. Some studies have shown LCFF has greatly improved test scores, graduation rates, college attendance, and future earnings. One study in particular found LCFF led to a sizable boost for 11th grade test scores especially. However, others have been more pessimistic. One study found that after 2013, California graduation rates increased by six percentage points (a huge win), but test scores have barely inched upwards. What’s clear is that more money hasn’t meant less problems. Why?

Part of it is because LCFF’s implementation is flawed. According to Lafortune, around 20% of low income students go to school in high income districts, who did not receive a funding boost under LCFF. Moreover, 43% of non high-need students attend schools in high-need districts. The money doesn’t follow students. It goes to the districts.

There’s also very little accountability and transparency in spending. Furthermore, as Gao points out, “even though LCFF provides more money, up until very recently, compared to the nation as a whole, California is still underspending… most money didn’t go to the students. They went to the staff. And schools are also hiring more inexperienced teachers. So I think because of all of those things LCFF has yet to show promising results.”

However, the LCFF is not the cure all primarily because, as Gao writes, “Generally speaking the majority of the variation in student test scores (like SAT/ACT scores, and proficiency scores) are attributed to factors outside of schools’ control. Those factors include parental education, family income, socio-economic status, poverty, parental involvement etc. So schools cannot single handedly solve the problem, because the underlying causes are multifaceted.”

Basically, in the absence of outside help, family is destiny. Households with more money can provide kids with more resources: functioning internet, educational devices, supplies, textbooks, SAT/ACT prep courses, tutoring, and more. Furthermore, wealthier parents have more time on their hands to help their kids with assignments and be more involved in their schooling—going to PTA meetings, parent teacher conferences, etc. Moreover, wealthier parents tend to be higher educated parents, and so they are more likely to have the knowledge to help kids with their homework. What’s more, wealthier parents can donate to schools, allowing schools to pay teachers more and offer more resources. According to Lafortune, about 80% of poor students attend schools in poor school districts.

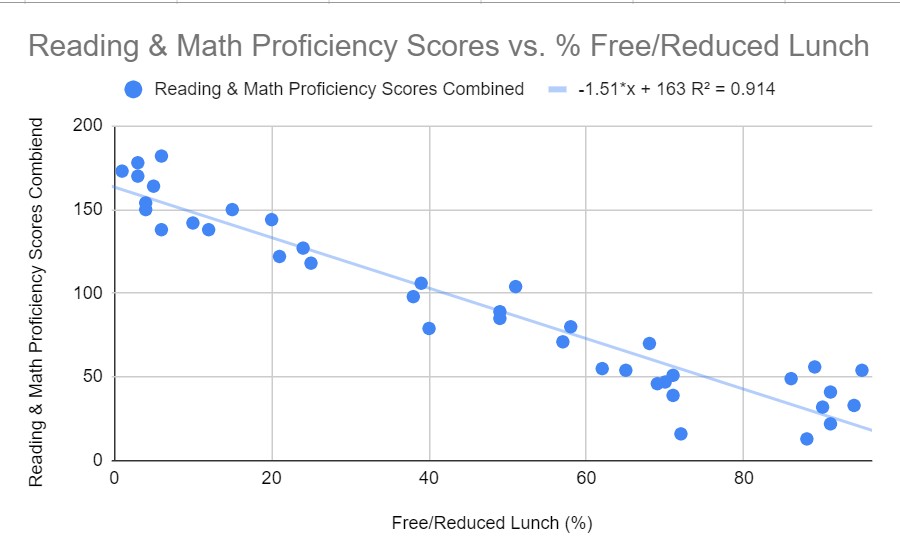

To test the correlation between poverty and school performance, I looked at traditional public high schools from 14 East Bay high school districts: Acalanes, Alameda, Albany, Antioch, Berkeley, Emery, John Swett, Martinez, Mt. Diablo, Oakland, Piedmont, Pittsburg, San Ramon Valley, West Contra Costa. One of the schools I looked at was my own high school, Miramonte High School. There were 38 schools in total. There was a super high correlation between lower poverty and higher math and reading scores.

For the stats geeks (everyone else, read if you dare), I measured poverty with the percent of students at each school who qualify for free or reduced lunch. The correlation coefficient between free and reduced lunch and an aggregate of reading and math proficiency scores was -0.955, nearly perfectly negatively correlated (with -1 being the most perfectly negatively correlated of course)! In English this means that to a super high degree, when poverty goes down, math and reading scores go up.

That being said, the correlation between lower poverty and higher graduation rate was only moderate (a correlation coefficient of -0.64 for the stats geeks). When poverty declined, graduation rates went up but the connection isn’t super strong. Granted, this wasn’t random sampling, the sample size is small, this is only the East Bay, this doesn’t control for other factors, and correlation doesn’t mean causation.

Put another way, California’s educational achievement is so unequal because California is so unequal. California has the seventh highest income inequality in the United States, and has the nation’s highest poverty rate. Lafortune puts it succinctly: “We have a lot of inequality here. We have a student population that is more disadvantaged than most other states… Our funding is certainly not compensating for that, at least compared to other states.” California policymakers must address the root causes of economic hardship for so many in our Golden State: California’s extremely high cost of living exacerbated by its housing shortage, not enough good high paying jobs, underinvested neighborhoods, healthcare costs, taxes, regulations, wage stagnation, drug addiction, single parenthood, racial discrimination, and more.

Along with socioeconomic divides, California education inequality is driven by race. Currently, Asian students and white students are more proficient in reading and math than Latino, Native American, and African-American students, even controlling for socioeconomic status. Graduation rates show similar disparities. In 2019, 94% of Asian-American students graduated, compared to less than 75% of Native American students.

I asked Gao and Lafortune to explain this racial gap. Gao highlighted many factors. First, Latino, African-American, and Native American students tend to be poorer than Asian and white students. We’ve already observed the profound effects of socioeconomic status on educational outcomes. Part of this is the digital divide—poor students having less reliable access to the internet and internet devices, especially important during the pandemic. Second, poor students, disproportionately Black and Brown, mostly live in poor school districts, which have more inexperienced teachers and less resources. Third, according to Gao, teachers and administrators exhibit racial bias against Latino, African-American, Native American students in the form of grading, course placement, course recommendations, disciplinary policies, and administrators pushing Asian and white students to pursue four-year colleges while steering other racial groups to the trades.

Lafortune too mentioned disciplinary policies and the school-to-prison pipeline. He also pointed out that Black and Brown kids are less likely to attend pre-school than their white and Asian peers. They enter kindergarten behind. With that, Black and Brown kids are disproportionately exposed to toxic chemicals like lead, which causes learning disabilities.

Solutions to these problems include making pre-K and preschool more accessible for all families, a key priority for Governor Newsom. While changes in state policy have driven down suspension rates across-the-board in the last decade, a great way to decrease the effect of bias from administrators and teachers is hiring more non-white people in those positions. California teachers are disproportionately white. Teachers can better reflect the communities they serve.

To be sure, California’s K-12 educational performance has been improving. Per pupil spending has increased as California has recovered from the 2008 Recession and more tax revenue has come in. Poor school districts are receiving more money because of LCFF. Test scores in reading and math, for all racial groups, have risen, albeit slowly, and graduation rates have gone up considerably for all groups. Governor Newsom is using considerable portions of California’s large surplus to fund schools, also expanding transitional kindergarten to include all 4 year old’s by the 2025-26 school year. California’s 2022-2023 budget increased K-12 education funding, and is meant to address many problems: enrollment decline, tutoring, learning strategies, literacy, mental health, school facilities, school transportation, career pathways, and more. California has also become the first state in the nation to offer free school meals to all students, creating a Universal Meals Program.

But, it’s not nearly enough. California still ranks near the bottom of the nation in spending, and California’s politicians aren’t tackling the main drivers of the achievement gap—the income gap and the racial gap. Schools are a reflection of society, yet they are tasked with curing all of society’s ills.

As Lafortune puts it, “Do we expect schools to be the silver bullet to kind of fix things we think are more broadly defined by all sorts of socioeconomic factors? Maybe this is a bit pessimistic but I don’t think schools alone are going to be able [to], maybe with insane amounts of funding… Are they really able to completely reverse the gaps that exist for all sorts of other reasons in society based on income, class, race, segregation, neighborhoods, health, all of the above?… If we really want to equalize opportunities and diminish and kind of end inequities that kids kind of grow up with, it probably can’t just be the school that does that either.”

Until California policymakers effectively fight poverty, lower socioeconomic and racial inequality, promote socioeconomic mobility, and fund the schools, education will never be the great equalizer.

Featured Image Source: KSBY