In 2023, beauty standards reign supreme, seemingly stony and impossible to truly change or avoid. Yet, throughout history, the definition of a “perfect” body has been incredibly transient depending on the time and place in question. From the Paleolithic curves of the Venus of Willendorf to the jutting collarbones and translucent limbs of the nineties “heroin chic,” it seems every generation of women must contend with a new impossible body to achieve. This standard cannot be attributed to female vanity, nor can we place blame entirely on male desire. The primary culprit for the dangerously malleable definition of the ideal figure is the economy.

There have been several cultures throughout global history that have shared specific definitions of ideal traits, often consisting of a plump, healthy figure, pale skin, and delicate features. These traits were hallmarks of the aristocracy: tanned skin meant long hours spent outside, something easily avoided by the rich but absolutely necessary for the agrarian peasant class. A softer figure pointed to a financially comfortable past and present, with a lean frame bearing heavy association to the malnourished lower class. Societies throughout history have subscribed to beauty standards with such qualities, from baroque France to Ancient China. Yet, these ideals are almost the complete opposite to the modern Western beauty standards we currently contend with. Now in the developed world, thin is in, and fake tans are all the rage. The reasoning behind our modern definition of perfection, while resulting in vastly different standards, does not stray very far from the rationale of our predecessors. With fattening foods being all too easy to access, while nutritious items such as produce and even eggs are getting more and more expensive, thinness is the new social currency. However, our modern economic context has added some nuance to the ebb and flow of the perfect body, and that is primarily due to the cruelly transient nature of capitalism.

The beauty industry has existed in some form or another as far back as 4,000 years ago. Grooming is imperative to the human psyche, thus throughout history people have put some level of care into their appearance. The earliest cosmetic products can be traced back to the Ancient Egyptians, who used natural ingredients such as minerals and fruits to create a modest array of makeup products. For most of makeup’s history, everything from rouge to kohl was made in small-scale batches from locally sourced ingredients. It wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that the beauty industry truly began to resemble the powerful force it is today. Industrialization allowed beauty products to be churned out at alarming rates, and the manufacturing of cosmetics supplied jobs for lower class women who would work in droves to cheaply produce thousands of lipsticks, mascaras, and blushes each day. As manufacturing technology continued to advance, so did the impact the beauty industry had on women of all classes and situations. While many cosmetic titans still advertise their products as a loose form of self-care, the reach of the beauty (and by extension fashion) industries has become dangerously potent as we continue to technologically and economically shift.

The most obvious and perhaps damning example of the environmental and psychological impact of the beauty and fashion industries is the twenty year rule. The twenty year rule refers to the life cycle of trends, which for the past century have somewhat repeated themselves every twenty or so years. The eighties took inspiration from the bold colors and innovative silhouettes of the sixties. The nineties saw a rise of muted tones and baggy pieces reminiscent of the

1970’s. The twenty year rule represents the ever-changing nature of modern trends, as prior to the twentieth century, trends in fashion and beauty were far more stagnant. This constant shifting of the hottest silhouette has caused a parallel trend cycle not pertaining to clothing, but rather our own bodies. Trends pertaining to our physiques (particularly those of women and girls) have for the past century been so distinct that the average American woman can conceptualize an accurate timeline of the perfect body. The reason for this pattern isn’t random- we can almost solely attribute it to the strategies employed by the fashion and beauty industry to reap maximum profit. Trends require us to update our wardrobes beyond what is practical. They additionally allow brands to cheaply produce products designed for deterioration. However, this pattern has also led many to believe that their own body is as subject to change as the latest fashion.

That system brings us to the terrifying state of the eating disorder crisis. When you think of a person with anorexia, what image comes to mind? For many of us, the first thing our brains conjure is likely a vain, delicate caucasian woman, gingerly picking at a lettuce leaf or apple slice. There exists a common misconception that those who suffer from eating disorders are primarily young, thin, white women. In spite of this, anybody can be a victim of this mental illness, and around nine percent of the US population will struggle with an eating disorder at some point in their lives. Eating disorders were not always the societal parasite they are currently. For much of history, self-induced starvation was often done for religious purposes, such as the starving girls of the Victorian era or the ceremonial fasts performed by Buddhist monks. In spite of this, we still see examples of people succumbing to disordered eating long before it became so common. Ancient Romans were known to purposely purge their food in order to indulge in as much lavish cuisine as they could. Empress Elisabeth of Austria was infamously obsessed with tight lacing her corset, and was known to excessively exercise in order to achieve an ideal waist circumference. The latter example resembles the reasons many modern individuals excessively control their food intake:the constant pressure to emulate what our current decade views as most desirable. Our modern economy has only served to exacerbate this need—capitalism profits off of eating disorders.

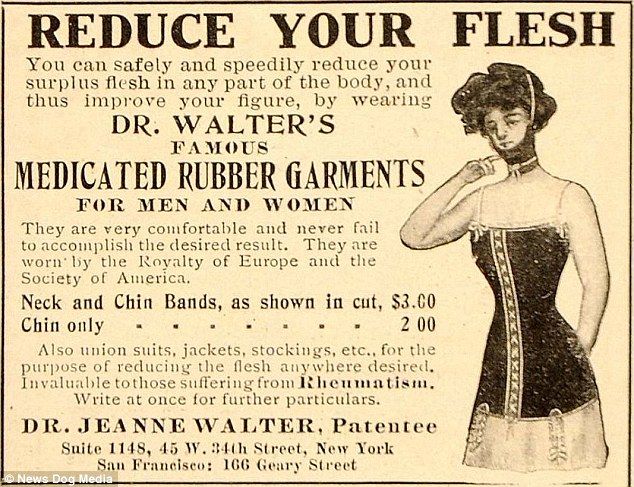

The 1930’s saw the start of several things: the Great Depression, consistent promotion of capitalism in the media, and a fear of weight gain. Here came a perfect storm: fashion brands began to increasingly promote the thin woman as the ideal wearer of clothes, while “wellness” companies profited off of the subsequent rise in body dysmorphia by promoting unhealthy weight loss methods. Thus, the foundations were set for an epidemic of the deadliest mental illness, whose reign of terror was fully funded by the fat cats of fashion. This setup created a narrative for the logic behind eating disorders—I can only be happy if I am accepted, and I can only find acceptance if I am beautiful. In our modern capitalist society, to be attractive is to live with ease, thanks to the control the fashion and cosmetic industries have on our own insecurities. Yet there is nothing easy about eating disorders, which pose a perilous 20% mortality rate, making them deadlier than any other mental disorder (aside from opiod addiction) including manic depression and schizophrenia. This statistic does not include the nearly 30% of people with eating disorders who attempt suicide.

The change in our cultural perception of obesity to now be linked with poverty rather than financial comfort is largely due to the food deserts many lower class individuals are trapped in. This problem means that most poor people in America primarily have access to highly processed foods, which make up for their lack of nutrition with heaps of saturated fats, processed sugars, and chemical coloring. Fatness’s connection with the lower class has enhanced the association between existing in a larger body and being lazy. Capitalism rewards ambition, or so we’re taught to believe. Thus, obesity becomes more than just a hallmark of unattractiveness—a fat person is a quitter. Restrictive eating disorders require a person to completely disregard their survival instinct, a dangerous habit that often gives the sufferer a euphoric feeling of false control. In spite of the danger, this sense of a grip on one’s life has made eating disorders increasingly alluring. In 2018, roughly 6% of Americans suffered from some form of eating disorder (including bulimia, anorexia, and binge eating disorder). By 2020, that statistic had increased to nearly 10%, and it is now estimated that nearly 30 million Americans suffer from the illness. In spite of this, psychiatric treatment has only gotten pricier, as companies churn out new diet pills and laxatives to soothe the stress caused by the onslaught of thin, perfect women constantly shoved down our throats.

Some companies have feigned progression by introducing plus-sized models into their campaigns, Unfortunately, it is rare that even these bigger models represent the physique of the average American woman. Films and TV shows such as Skins or To the Bone portray anorexics as tortured and dainty, and several social media platforms from TikTok to YouTube are flooded with content promoting dangerous restrictive patterns. In this whirlwind of calories and fatphobia, the puppet masters of the beauty industry target younger and younger girls, as the tide of capitalist calorie counting continues to drown millions of Americans.

Featured Image Source: DailyMail

Comments are closed.