Free speech comes at a steep price for the UC Berkeley campus: since the election of Donald Trump, the campus has put $1.5 million, taken out of a meager $2.6 million operations budget, towards the protection of free speech. This does not include the expenses the City of Berkeley was left with following the damages of the Milo protests. In a public university where in-state tuition runs about $14,000 a year, this seems to be an extraneous cost to a campus already ridden with a $77 million deficit. Many are left to wonder whether money or the freedom of expression holds more value on our campus.

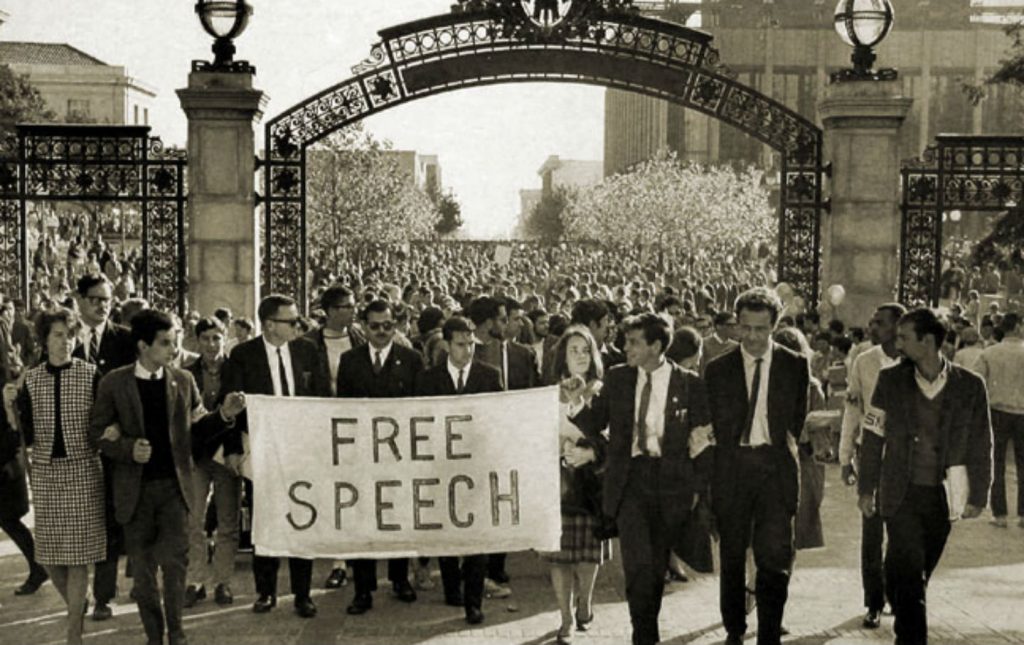

UC Berkeley is a place of safe spaces, politically correct vernacular, and activism for minority, LGBT, and women’s rights. The majority of the school identifies as liberal, and many on the left see UC Berkeley as a beacon of political hope in a chaotic world. This viewpoint originated in the Free Speech Movement of the 1950s and 1960s — when students started protesting the campus regulations on freedom of expression. The university limited their speech and, in response, the students organized protests against the university in defense of free speech. Subsequently, the advent of the Vietnam War and the opposition it garnered continued the presence of protests on campus, and the rest of Berkeley’s liberal image is history.

Yet, what was Berkeley like before the 60’s? Has UC Berkeley always been a safe space for liberal thought? In a word, no.

UC Berkeley was founded when the private College of California merged with the state-sponsored Agricultural, Mining, and Mechanical Arts College to become the University of California in 1868. The first men to enroll in and graduate from UC Berkeley were required to train and serve in the military, a requirement that continued until 1904. The campus’s North Hall even served as an armory during this time. While this initial military requirement contrasts with the UC Berkeley of today, this pro-war tradition continued through the World Wars into the first half of the 20th century.

The UC Berkeley students and faculty, prior to the Free Speech Movement, often rallied behind the national war efforts –– both Memorial Glade and Memorial Stadium were dedicated at this time to the fallen soldiers and veterans of World War I. With the onset of World War II, the Army contracted Berkeley’s Ernest Orlando Lawrence Radiation Laboratory to help develop the atomic bomb. This led to the discovery of plutonium in Gilman Hall and the naming of UC Berkeley’s Professor J. Robert Oppenheimer to the head of the Manhattan Project. Oppenheimer is a beloved aspect of Berkeley’s past –– my daily trek up Oppenheimer Way brings to mind this great man’s scientific discoveries and the political impacts they had.

The Civil Rights movement inspired activism on the Berkeley campus, yet campus rules at that time forbade the distribution of flyers or outspoken political discourse on university property, specifically on Sproul Plaza. To make a long, complicated history short, the campus and the students battled for many months over the issue of free speech, culminating in a massive sit-in in December of 1964. The campus gave in and lifted all bans on political activity on campus following this sit-in, yet the Berkeley protesters realized they still had a battle to win off-campus.

Berkeley students continued to fight specific, bureaucratic bans on speech, such as time limits, while beginning to protest the Vietnam War through the skills they had developed in the Free Speech Movement. The protests against the Vietnam War garnered the attention of the public, and especially that of the rising politician Ronald Reagan. Reagan was a part of the rising conservative wave washing over California and thus he adamantly was against giving the Berkeley students the space to protest the Vietnam War. As many politicians have the habit of doing, Reagan made campaign promises in the race for governor that were vague and easily appeased the public: he would “clean up the mess at Berkeley”.

However, the protests of the late ‘60s were not so much like the fight for free speech that preceded them as they were the first battles testing the limits of the protections of the First Amendment. In May of 1969, at the request of the Berkeley mayor, Governor Ronald Reagan declared a state of emergency and sent 2,200 National Guard troops into Berkeley. Dozens of people, both students and troops, were injured, and one student died on this day, which was later named Bloody Thursday. This was the first major off-campus battle over Free Speech; and as we find ourselves returning to this battlefield, might we suggest that history is repeating itself?

In the polarized political world that we call our modern times, both sides of the aisle call for a protection of their free speech, yet this hits a roadblock when individuals only want to protect the speech that they agree with. Constitutionally, UC Berkeley must protect the right to free speech –– according to former Berkeley law dean and constitutional law expert Jesse Choper, “the University of California is a public institution and therefore it’s governed and bound by the free speech clause…. There are time, place and manner regulations and those… are very elastic.” Although free speech is a protected right, protesting others’ speech is also free speech. Many students have lived through the protests that come to the nation’s mind when free speech is mentioned –– I personally get antsy whenever I hear helicopters now. Yet, how do we as a campus react to this conservative resurgence of the Free Speech Movement? What is the campus doing to address these growing issues? And most crucially, who is paying to protect free speech on the UC Berkeley campus?

I spent a sunny afternoon indoors in the ASUC Senate Chambers to listen to varying opinions on campus as to what the university should do in regards to the monetary concerns that surround the protection of free speech; this is a part of the strategic planning process to determine the course that UC Berkeley will take over the next decade. Both the Berkeley College Republicans and the right-wing publication Berkeley Patriot had representatives at this public forum to advocate for the further protection of free speech. Both clubs argued that their goals were not violence, but rather to create a dialogue between individuals with different political ideologies. This sounds very similar to what the original members of the Free Speech Movement were trying to do: create the space to have an open dialogue about their political and cultural views. Yet, unfortunately, the past year and a half have demonstrated that violence has resulted in response to various conservative-leaning speakers, necessitating campus involvement and the formulation of new policies.

Regarding the strategic planning process, Chancellor Carol Christ released a statement: “I believe that we must collectively establish a cohesive, well-reasoned, and ambitious vision of what our university should be in order to properly set institutional priorities and determine campus investments.” Among these conversations are both the financial obligations of the university and the university’s role in larger worldly issues: this is directly connected to the conversation of free speech. The conversations surrounding the chartering of the new plan are all the more crucial as it will determine whether the university will support the continuance of free speech on campus.

The dominant debate is whether speakers that require the protection of such large sums of money as the $800,000 spent for Ben Shapiro’s talk in September 2017 are worth it in the name of free speech. When considering this dilemma, the campus should take into consideration who benefits from these talks and who is at fault for the violence that breaks out when conservative speakers come to campus. The main beneficiaries of these talks are the conservatives on campus, yet as Bradley Devlin, president of the Berkeley College Republicans, mentioned at the Free Speech Commission, these speakers also promote a conversation between individuals of different political opinions. The more difficult question is who is at fault for the violence that breaks out. While many would look at Milo Yiannopoulos’s hate speech and quickly conclude that it is his fault (an idea that I personally see as an easy way out as Milo is very easy to despise), constitutionally, the protection of free speech includes the protection of hate speech so long as the hate speech does not invoke immediate violence. The most recent Supreme Court case regarding hate speech was Matal v. Tam, which determined that hate speech is, in fact, protected by the First Amendment. Thus, regardless of the disturbing rhetoric that Milo utilizes, his speech is protected. Who, then, is left to blame? Mr. Mogulof, a spokesman for the campus, claims a group identified as Antifa is most likely at fault for the violence on the night of Milo’s speech and the threat on the night of Ben Shapiro’s speech. “This university was essentially invaded by more than 100 individuals clad in ninja-like uniforms who were armed and engaged in paramilitary tactics,” Mr. Mogulof said after the February riots. “They were implementing a very clear plan to engage in violence, disruption, and property destruction.” Berkeley is now put in a position of having to decide if their historical ideals of free speech hold up for conservative dialogue or if the monetary aspect of protecting its students is too much for the public university to handle. And consequently, if it is too much money for a university to handle, should it be expected that small, student-run organizations must pay these security costs?

Berkeley’s Principle of Community, states that “we are committed to ensuring freedom of expression and dialogue that elicits the full spectrum of views held by our varied communities.” UC Berkeley also has a high priority in protecting the safety of its students and campus. Thus, this debate comes down to money –– as most issues typically do. Must the campus continually fork out the money to protect speakers that bring violence to campus? In an unfortunate catch-22, the campus should continue to protect these speakers in order to continue the protection of free speech. The monetary obligations are high, especially for a campus with a large deficit already, yet the campus needs to stand behind its ideals and the rights protected by the Constitution. While many on campus do not see these conservative speakers’ dialogue as a high priority, UC Berkeley has a historical, moral, and legal obligation to promote the freedom of speech. If UC Berkeley, a diverse university known for its high academic achievements, does not actively protect free speech, then what can we expect from the rest of the nation?

Featured image source: The College Fix

One Comment