From Trump’s election through his decision to pull out of the Paris agreement, doomsday predictions about Trump’s approach to climate policy have largely mellowed to anxious reassurances that all is not quite lost. Rather than causing a collapse in American resolve to fight climate change, Trump’s public repudiation of the Paris agreement spurred American mayors, governors, and corporate leaders to reaffirm or even increase their commitment to address climate change. Countries likewise reaffirmed their commitments to the Paris agreement, with several major emitters announcing plans to ban internal combustion-reliant cars.

When the moment arrived for China to assume leadership, Xi Jinping pointedly declined to put pressure on other countries, instead repeating China’s prior commitments. Peking University Economics professor Chris Balding told CNN “I’m hesitant to call [China] a true leader on climate change but it is a de facto leader. This has fallen into its lap.” Although the Chinese Communist Party is unlikely to assume the mantle of global leader any time soon, the energy market has changed so rapidly within the last year and a half that it is plausible that China can fit ambitious carbon-cutting goals within a broader set of strategies to transform the economy from manufacturing to high-value services. In order to become a true leader in clean technology, however, China will need to rapidly scale-up R&D and deployment by reforming the financial market.

Managing the Transition

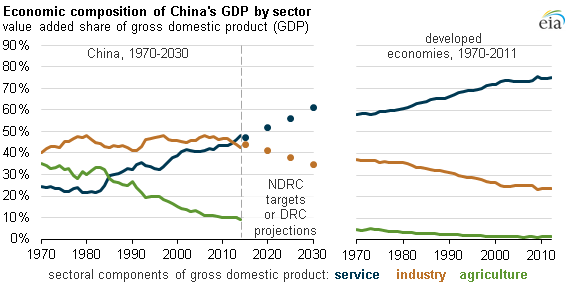

As part of its strategy for staying in power, the Communist Party undertook a massive top-down mobilization of resources starting in 1979. The strategy brought labor together with capital in special economic zones to catalyze growth and global trade. China’s stellar economic performance took advantage of cheap labor and economies of scale to build large-scale industrial projects financed by top-down investment from state-owned banks. While successful, this strategy has its limits: where do you find extra growth once everyone is in the workforce? Since the 2008 recession, McKinsey, a consultancy, reckons that China has been moving towards an economy much like America’s: characterized by a large service sector bifurcated between high-value-added services (finance, information technology, pharmaceuticals, healthcare, education etc,) and low-value-added services (retail, custodial, sales, consumer services, etc.).

Clean technology can be a leader in growing the high-value-added industries the country will need to shore up flagging growth rates. By supporting advanced manufacturing and investing in R&D, the sector can have high spillovers which support other sectors.

The bulk of high-value-added R&D in China’s clean energy sector is done on or near the factory floor: $1.4 Billion was invested by solar manufacturers in basic research between 2006-2015, compared to just $74 million from the government. This means that clean technology in China could become a leader in advanced manufacturing, which combines information technology and R&D with traditional manufacturing. Developing these capabilities could have massive spill-overs to other sectors like heavy industry, information technology, finance, and high-skill services. China might be able to stem the bleed of manufacturing jobs to lower-wage countries and develop high-skill industries to replace traditional manufacturing quickly via this strategy.

This all takes money, which China has a lot of. But in order to manage this transition, China will need access to a different, broader set of financial instruments. As China watcher Kenneth Lieberthal of the Brookings Institution noted at a discussion panel last summer, “if China is going to reach solar deployment goals that are as aggressive as the ones that it has enunciated, it needs to get much more efficient in the way that it deploys its money and the way that it spends its money.” The problem for China is not the size of its capital stock, but how efficiently it can be spent.

Answers Blowing in the Wind

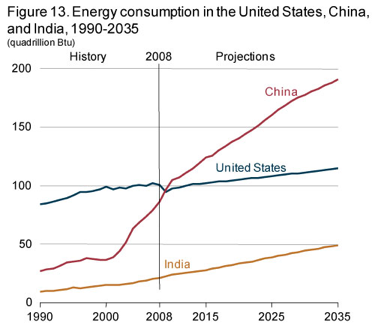

Higher R&D investment with advanced manufacturing will be necessary to meet the 2 degrees Celsius target announced by world leaders in December 2015. For context, the current stage of global renewable energy deployment is a straightforward numbers game: build as many solar panels and wind turbines as the market will bear to push down costs and stimulate innovation. Trade between China and the US has been characterized by specialization according to comparative advantage: cheap labor in China and cheap capital in America (comparatively speaking) means that American firms and institutions work to lower the cost of renewables through technological breakthroughs and China mobilizes its labor pool into factories to achieve economies of scale in solar cell and wind turbine production. Both sides of the equation — technological breakthroughs in America and mass production in China — were instrumental in making new solar installations cost-competitive with new fossil fuel installations. New renewable energy now costs about $0.07/kWh, slightly above the cost of building a new coal-fired power plant, and a milestone that was hit years — if not decades — ahead of expectations. However, this is still not cheap enough to begin replacing existing coal-fired power plants which will be necessary to meet the Paris Agreement’s 2 degree Celsius target.

Yet the ticking clock of climate change means that many potential solutions need to be researched and deployed at scale before the relative merits of different strategies become apparent. In other words, the kind of decentralized efforts best-suited to free markets. New technologies leveraging economic growth may have grabbed headlines, but such growth curves typically take a long time to ramp up; it took almost 40 years for solar power to reach cost competitiveness and it still accounts only for 1% of US electricity generation. The demands of decentralized, highly intensive investment are for diverse and complex financial services and capital markets. Thus, access to diversified financial instruments and deepened financial markets will be necessary not only to meet domestic economic targets but also commitments on clean technology deployment.

Funding the Future

Like the rest of China’s economy, clean tech sectors will increasingly demand human capital and debt financing mechanisms. This is particularly important in China where the bulk of R&D spending on solar technology is spent by companies rather than government entities. Compared to the US — where the majority of basic research is undertaken by the federal government — private sources of finance are especially important for China’s emerging clean tech industry.

Yet most of the financing options available for enterprises — whether manufacturing, basic research, or deployment and installation — are short-term, high-interest loans. The Chinese financial industry is dominated by large, state-backed banks which provide this short-term lending. This might satisfy the need for short-term financing helpful for the deployment of renewable energy but these instruments are ill-suited to providing equity, insurance, and long-term financing many borrowers would prefer for basic research and advanced manufacturing. Silicon Valley’s series of high-value innovations were fueled almost entirely by equity provided by venture capital rather than traditional short-term loans. Moreover, state-owned enterprises receive a disproportionate share of state-bank lending, drying up funds for more competitive projects. This huge mismatch is responsible for a large part of the inefficient allocation of capital that is such a drag on China’s economy.

Despite awareness of these challenges among Communist Party leaders, reforms have failed to match up to the often-ambitious rhetoric. Xi Jinping entered office on the promise that free markets would play “a decisive role in allocating resources,” but to most western commentators, Mr. Xi has not lived up to his own rhetoric.

One problem is that the Communist Party routinely uses state-owned enterprises to pursue political goals. State-owned enterprises (SOEs) are being leveraged to provide a bulk of the funding for China’s One Belt One Road which involves often-unprofitable infrastructure investments, while at the same time being told to make more productive investments. These diktats have been unsuccessful in creating an incentive for better performance — SOEs earn an abysmal 2.9% return on assets — and Xi Jinping’s focus on restoring the centrality of the Communist Party has left economic goals by the wayside.

Yet liberalization of financial markets serves some political goals. The large shadow banking sector owes its existence to the gap between what kinds of financing companies need and what is officially allowed by the Communist Party. In the words of Douglass Elliott, Arthur Kroeber, and Yu Qiao at the Brookings-Tsinghua Center, “The problem for China’s financial authorities is that the very large traditional banking sector is not fully serving the increasingly complex financial needs of an economy transitioning from a focus on industry and infrastructure to one based mainly on consumer services.” As the Communist Party learned from its bungled intervention in the stock market, the government possesses few deft tools to reign in credit markets or direct investment to serve national goals: bans and regulations often drive sectors underground, making it even harder to regulate them and more difficult to glean information about their dealings. This threatens the Communist Party’s ability to monitor and control potentially risky behavior. And although doomsday warnings of shadow banking bubbles have rarely been prescient, the excruciatingly slow growth China has experienced has put leaders on edge about any potential threats. Liberalized financial markets — if managed well — could not only increase the efficiency of capital allocation but also bring a large segment of China’s economy into the light, making it easier for the Chinese Communist Party to control these activities.

This also provides modest political dividends to the party: loosened markets can help allocate capital more efficiently, giving another boost to growth that the Party will need to retain its legitimacy. Moreover, liberalized financial markets would help develop clean energy technology by enhancing high value-added parts of the supply chain and help sustain Chinese manufacturing by increasing investment in hyper-competitive advanced manufacturing projects. Barring a major policy reversal, this is still unlikely; the Communist Party is unlikely to loosen the reins on financing and, therefore, will not be claiming the mantle of active leadership on climate change anytime soon.

Featured Image Source: The Quint

Be First to Comment