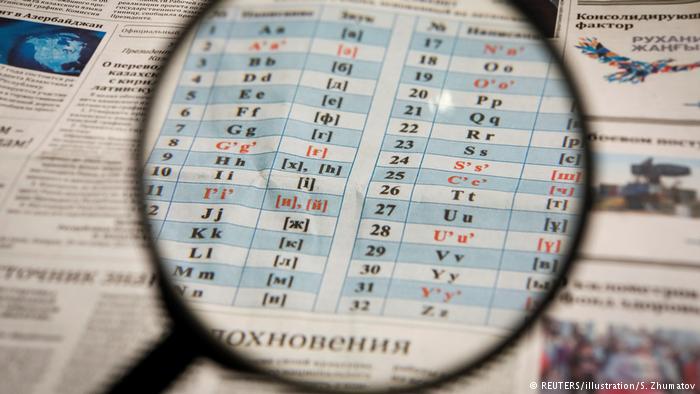

Kazakhstan is no stranger to changes in the national language. In the country’s history, the written script has changed four times while the language in question, Kazakh, has remained the same. Migrating from its original runic scripts, Kazakh adapted adopted Arabic script under the influence of Islamic traders in the 8th century, modified it slightly in 1924, changed it entirely to Latin-based letters in 1929 under the direction of the nascent USSR and converted it once more to Cyrillic in 1940 following Stalinist policy changes. The latest announcement from President Nursultan Nazarbayev to turn (or rather, to return) to the Latin alphabet by 2025 with the help of many, many apostrophes to make-up for the shortage of letters, therefore, is not greeted with rancor so much as ridicule and resignation. Social media users responded to the news with mocking new spellings of their names. One user pointed out that the Kazakh word for carrot, as it was spelled in its new Latin form, would resemble the romanization of a common expletive in Russian. Even the country’s own name, Kazakhstan, would be changed to Qazaqstan.

Expletive and Stick

Despite the mixed public reaction, the President staunchly defends his decision, citing “many reasons”, some of which are “specifical[ly] political”. In a nation in which language so often reflects its political leanings and allegiances, the move is being hailed by pundits as a sign of Kazakhstan’s rejection of Russian influence. Russian media, in turn, decried the move as the first step toward the marginalization of ethnic Russians living in the former USSR satellite. In a dramatic article published by British tabloid Daily Mail, the sensationalist headline reads: “Kazakhstan’s President snubs Russia!” However, the move in its nuances does not, in fact, signify true repudiation of the country’s biggest trading partner, with whom Kazakhstan shares its longest border. Many former USSR-satellites, including Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan, have already switched to the Latin alphabet. If anything, Kazakhstan has been more cautious in distancing itself from its northern neighbor. Moreover, the status of Russian within the country will not change—it will remain as one of its official languages, as it is currently spoken by 85% of Kazakhs. This particular change is more reflective of the nation’s desire to modernize through Westernization by adopting a form of writing closer to that of the commercially-produced computer keyboard and the language of global trade while developing its national identity. Whether the change is truly effective remains to be seen.

Tomorrow, the World

In the days following the announcement, perhaps to counterweight the amount of cyber scorn, the media network Kazakh TV, formerly owned by the President’s daughter, published an article quoting the positive reactions of various academics to the change at a conference in Istanbul: “…the steps of President of Kazakhstan are welcomed regarding the opportunity to historically join the Turkic world.” commented Mikhail Rodin, a Latvian professor, “On the other hand, in my opinion, the transition to the global zone of English won’t be a big and serious problem.” The “Turkic world”, apparently, sees Kazakhstan’s change as an attempt at conformity with its Turkic-language neighbors, all of whom now employ the Latin alphabet in their written forms. The appeal (and congratulatory back-patting) of forming a unified Eurasian identity in employing the same syllabary is the same rhetoric which, along with Turkish donations of many Latin-language typewriters, convinced post-Soviet Azerbaijan to replace Cyrillic with the ABC’s it utilizes today. The transition, however, was far from painless. Disagreements on which symbols to use and how abounded, as scholars were caught in the dilemma of creating a script that both conforms to and is distinguishable from other Latin-alphabet languages in the region. The debate over whether an “eh” sound in the language would be written as “e” or “ä” raged for months. Ultimately, the debate became more about distinguishing Azerbaijan as a nation with its own unique symbols in writing that any sort of neighborly rapprochement or camaraderie.

Another case for switching alphabets, interspersed liberally with free-market economics, argued that a shared alphabet with the West at large would make for more better economic ties with such powerhouses as the US, UK, and the European Union. Turkmenistan, which had also transitioned as part of the movement known as “new alphabet disease”, perhaps in a hurry to declare its willingness to break into Western markets, almost designated its letter for the “ssh” sound as “$” in upper case and “¢” in lowercase. But a difference in alphabets has rarely, if ever, influenced the direction of trade and trade deals—if they had, nations such as China or Japan might have gone bankrupt with no other country to invest in their unique written forms. Moreover, all evidence suggests that younger generations are already gravitating toward the study of English, becoming fluent in the lingua franca as well as Kazakh and Russian. With only 62% of the population speaking Kazakh, more changes to the language seem not only impractical but unnecessary for what imagined trade benefits the modifications might bring. Once again, the issue seems to point to an intent to stir up national pride: part of the President’s strategy, Kazakhstan-2050, called for “a spiritual pivot” and an emphasis on the “state language” in the midst of “societal trilingualism”. A shift in Kazakh, so goes the theory, would make the language easier to learn and therefore more attractive to future speakers due to its increasing similarity to English. The only caveat, of course, is the irony of replacing an alphabet signifying foreign intervention and influence with an alphabet signifying nothing but global influence, all in the name of maintaining national integrity.

Apostrophe to the Apostrophe

Already, Kazakhstan looks poised to encounter the same problems Azerbaijan and Turkmenistan faced with their new scrips. The government decision to employ its own form of Latin alphabet rather than utilize Turkey’s resulted in mass ridicule of the proposed “apostrophe letters” such as a’ and p’, representing sounds not present in the original 26 letters provided. The Economist, for one, complained that the new script is “far from elegant”.

Concerns involving execution also surfaced. Unlike pre-transition Turkey, for whom 90% of the population was illiterate and would be taught in the new alphabet, Kazakhstan boasts of a 99.7% literacy rate. If, as the President decreed, the country was to have a new Latin codification of all Kazakh-Cyrillic spellings by the end of the year and a smooth transition within eight short years, officials would need to account for overhauls in the education system and teacher training along with the recreation of countless government documents, including forms, laws, money, archival material, passports. Professional jargon must also be taken into account, along with decades of archival material that would need to be dug up and converted. Back in 2007, a feasibility study conducted by the Ministry of Education and Science at the behest of the President outlined a six-step Latin-alphabet plan that would take at least 12-15 years and $300 million to implement. This time around, the government has announced no plan, has issued no budget, and has given it a time cap of eight years. With so much work ahead, perhaps the one bright side is that the intended letters of conversion happen to match the most commercially-available keyboard in the world. Too bad the symbols debate, for all its economic and labor costs, is merely symbolic.

Featured Image Source: Reuters

Be First to Comment