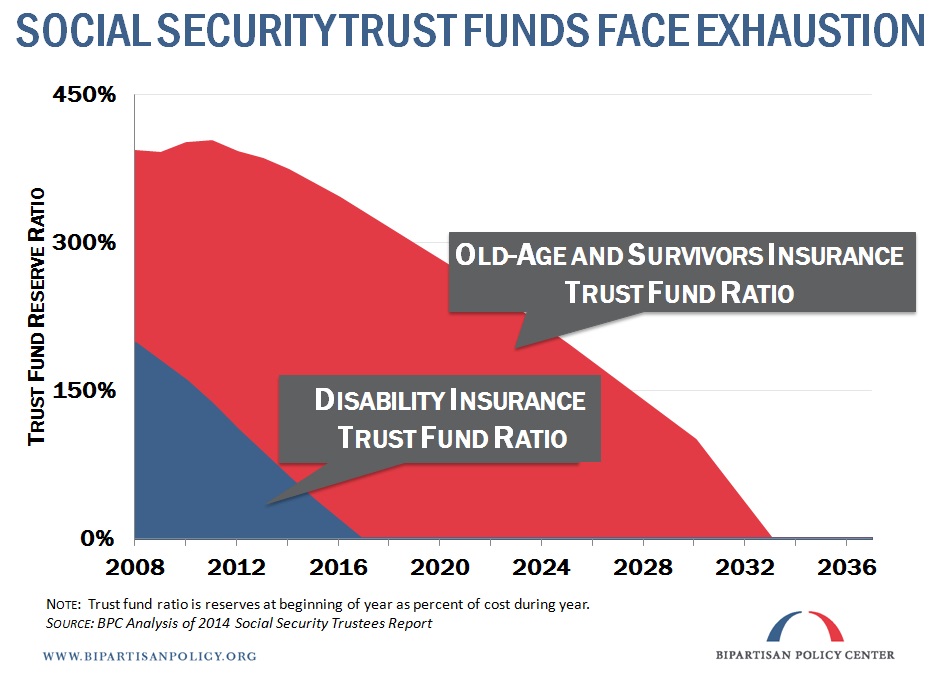

[vc_row][vc_column][vc_column_text]Ironically, for the future of retirement, past will not be prologue. In the decades ahead, America will confront some long term trends — among them declining birth rates and life expectancy gains — and we will be forced to reform our essential welfare programs, including Social Security. Because these population trends were less stark in previous generations, policymakers could overlook them and defer solutions, but decades later, the consequences have caught up with us: Barring reform, Social Security’s actuaries believe the program will become insolvent in 2034. Thanks to unremitting federal fiscal indiscipline since the Reagan era, we must reform Social Security if we hope to profit from it in our own retirement.

Even some who collect Social Security benefits have no clue how the program works. Social Security’s purpose today is the same as when it was enacted in 1935: to keep elderly people out of poverty. Beginning at age 62, anyone who has worked and paid taxes for at least 10 years can draw retirement benefits if they choose. The “normal age” of “full retirement” is 67, meaning that if one retires then and chooses to begin drawing benefits, they will get 100 percent of the benefits they could expect rather than getting reduced installments if they retired earlier to compensate for the additional time one is on Social Security. One can thus increase the size of the Social Security installments one receives by delaying retirement and collecting Social Security benefits later.

Source: Time

The program has, however, been expanded from its original form to include programs for the dependents of Social Security recipients and for the disabled. Medicare, the government-provided health care for the elderly, is also part of Social Security. Disability insurance (SSI) and Medicare both seek to keep those who cannot work out of poverty and ensure they have access to health care. But core Social Security retirement benefits have been curtailed since its inception and the retirement age has been raised, meaning the program is arguably less successful because it is now less generous; Social Security is, however, a more fiscally sustainable program, and its advocates must concede that reducing benefits has saved the program, which brings us to the issue of its solvency.

As with every federal welfare program, Social Security has multiple avenues of escaping default: we could 1) reduce benefits, 2) raise revenues, and/or 3) raise the retirement age. Given that welfare reform is among the most politically inflammatory issues in American discourse, each route is contentious, but each deserves consideration.

So, first, why not reduce benefits? Many — especially conservatives — would argue individuals should simply save more for retirement. It’s a tidy solution: If people are simply more financially disciplined, the government need never intervene. Social Security, however, does not merely restore to individuals exactly the income taken from them during their working years; it adds to it. For nearly everyone, Social Security benefits exceed their payments, according to a 2013 study by the Urban Institute — partly because only half the cost is deducted from one’s paycheck (employers pay the other half). Reducing benefits, however, has a key flaw: Increasing life spans entail greater expenses throughout retirement since longer lives do not necessarily mean proportionally greater years spent working. Other demographic trends compound the conundrum. The U.S. birth rate has been low for more than a decade, so the ratio of workers per retiree is in risky decline. If lifetime earnings do not keep pace with the years we draw on our savings (if wage growth remains as stagnant as in recent years), even simply maintaining current benefits won’t suffice.

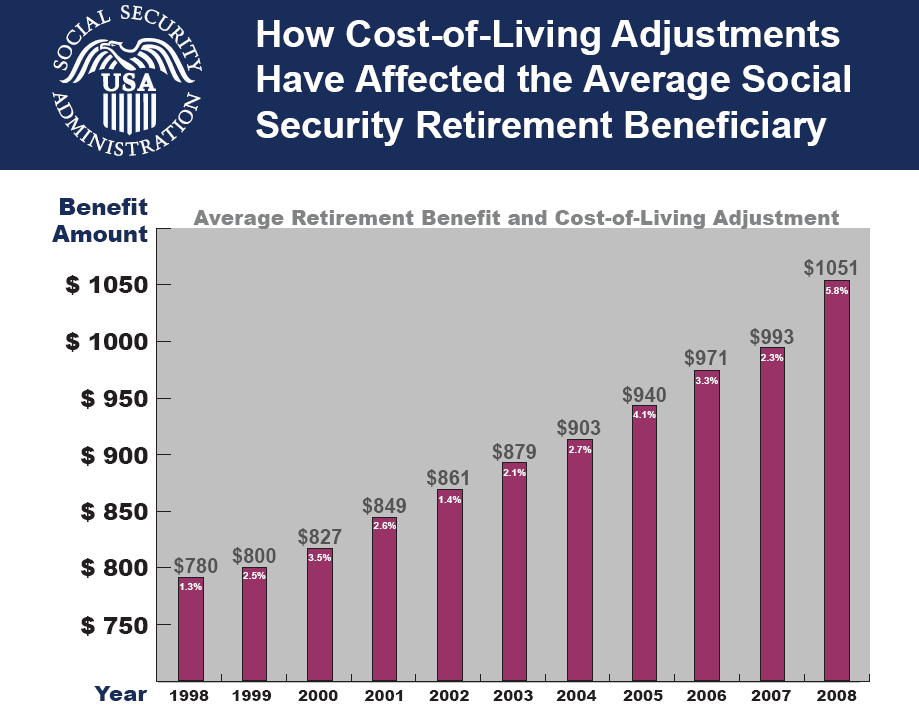

Fortunately, Social Security benefits are prudently indexed to inflation — so benefits will rise in nominal terms to maintain their present real purchasing power — but there is no adjustment mechanism to ensure Social Security can support people who simply live longer than once was normal. On average, the World Economic Forum projects people born in 1998 (like this author) will live to be 100 years old; circa Social Security’s implementation, life expectancy was around 60 years old. A program designed to pay benefits for about 13 years affords a paltry sum when distributed over thrice the time. Far from cutting benefits, it seems we need to boost them.

If we set benefit reduction aside, another possible recourse is to increase revenue — instantaneous political suicide. Before we find intricate new ways to raise funds, however, we need context for the government’s finances: Fiscal responsibility has been anathema in politics for decades, notwithstanding the vast chorus of hypocrites whose partisan quarrels obscure their failure to balance budgets. Congress’ most recent budget blithely ignored the danger of ballooning deficits, and the late 2017 tax law was nearly criminal in its dereliction of fiscal duty, engorging public debt for the foreseeable future. So it is naïve to pretend that a revenue-raising policy for Social Security must be carefully calibrated. The government simply must raise revenues soon – no matter the reason – and desperate times call for desperate measures.

Perhaps the best way of raising revenue would be reforming the tax code to eliminate loopholes (especially for corporations) and curtail deductions, but since that effort has already been botched, we must look beyond the corporate tax rate, where the most feasible first step is eliminating the cap on taxable income, which is currently $128,400. Essentially, income earned above the cap cannot be taxed to contribute to Social Security.

Generally, progressives love any proposal that raises revenue — for lack of a better term — progressively. Conservatives and libertarians, however, castigate Democrats for funding government programs by siphoning the wealth of higher earners. Yet simply removing the taxable income cap would apply the relatively sedate 6.2 percent levy on income to the wealthiest Americans: eliminating the taxable income cap would 1) vastly extend the solvency of Social Security and 2) marginally reduce socioeconomic inequality. Opponents note, however, that it would not be enough to rescue Social Security — insolvency would still arrive, just 75 years later.

Two other commonly discussed routes are lackluster: First, the Congressional Budget Office observes Social Security could slow its Cost-of-Living Adjustment (COLA), which pegs benefits to inflation such they gradually rise in nominal terms but retain their real purchasing power. Simply lowering the COLA, however, would amount to cutting benefits under the guise of a middling economic defense. Second, we could also deny the rich Social Security, a practice called “means testing.” This latter option has less conspicuous but more pernicious effects. First, there is real, intuitive power in affirming that a social welfare program is universal, not just for the most destitute — universal programs are more politically formidable because they feel like rights, not oft-stigmatized “entitlements.” Second, unintuitively, some forms of means testing would deduct Social Security benefits for those who continue to earn income, but because the poorest Americans are generally least able to save, they are disproportionately forced to work later in life to make ends meet.

Source: The Social Security Administration

So what else? Of the remaining options, only raising the retirement age seems to have rational justification. This is perhaps the most politically toxic option: Why indeed should Americans have to work longer than they used to for the same benefits? First, the demographic trends that strain Social Security also justify an older age of retirement. In our late 70s, we may not retain sufficient vim to work full-time and command the highest wages, but the projected rise in longevity will not be all frailty and disease: Human beings will be healthier longer, too. And we may need to act like it. Social Security’s deliverance seems worth a full retirement age of 70.

So it is not too late for Social Security. The odious fools in Congress currently bankrupting America’s posterity will be long remembered for their deplorable fiscal profligacy. But our financial stewardship will pay dividends if we can reform our social safety net soon. And sparing the elderly the indignities of penury may help us rest easier as when we go gentle into that good night.

Feature Image Source: Bipartisan Policy Center[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

Be First to Comment